This article may be in need of reorganization to comply with Wikipedia's layout guidelines .(September 2017) |

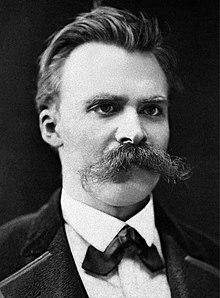

Friedrich Nietzsche's views on women have attracted controversy, beginning during his life and continuing to the present.

This article may be in need of reorganization to comply with Wikipedia's layout guidelines .(September 2017) |

Friedrich Nietzsche's views on women have attracted controversy, beginning during his life and continuing to the present.

Ida von Miaskowski was the wife of the economist August von Miaskowski, who taught at the University of Basel. Between 1874 and 1876 Nietzsche had close relations with her family. In her memoir of Nietzsche, published seven years after his death, she remarked:

In the eighties, when Nietzsche's later writings containing some of the oft-quoted sharp words against women appeared, my husband sometimes told me jokingly not to tell people of my friendly relations with Nietzsche, since this was not very flattering for me. It was just a joke. My husband, like myself, always kept friendly memories of Nietzsche [···] his behavior precisely towards women was so sensitive, so natural and comradely, that even today in old age I cannot regard Nietzsche as a despiser of women. [1]

Despite Nietzsche's writings being viewed as being misogynistic by many, others, such as Anthony Ludovici, insist that he is only an anti-feminist, not a misogynist. [2]

Lou Andreas-Salomé, who knew Nietzsche very well, claimed that he had proposed to her (according to her, she refused him) and that there was something feminine in Nietzsche's "spiritual nature". According to her, Nietzsche considered genius to be a feminine genius. [3] [ clarification needed ] [4]

Nietzsche wrote specifically about his views on women in Section VII of Human, All Too Human, which seems to hold women in high regard; but given some of his other comments, his overall attitude towards women is ambivalent. For instance, while in Human, All Too Human, he states that "the perfect woman is a higher type of human than the perfect man, and also something much more rare, " there are a number of contradictions and subtleties in Nietzsche's thought elsewhere which are not easily reconcilable. At times he could speak both in praise and in contempt of women, as in the following passage: "What inspires respect for woman, and often enough even fear, is her nature, which is more “natural” than man's, the genuine, cunning suppleness of a beast of prey, the tiger's claw under the glove, the naiveté of her egoism, her uneducatability and inner wildness, the incomprehensibility, scope, and movement of her desires and virtues." (Beyond Good and Evil, section 239.)

His attitude can sometimes be entirely disparaging: "From the beginning, nothing has been more alien, repugnant, and hostile to woman than truth—her great art is the lie, her highest concern is mere appearance and beauty. " In section 6 in "Why I Write Such Excellent Books" of Ecce Homo, he claims that "goodness" in women is a sign of "physiological degeneration", and that women are on the whole cleverer and more wicked than men—which in Nietzsche's view, constitutes a compliment. Yet he goes on to claim that the feminist campaign for the emancipation of women was merely the resentment of some women against other women, who were physically better constituted and able to bear children.

Other writings include:

"Woman's love involves injustice and blindness against everything that she does not love... Woman is not yet capable of friendship: women are still cats and birds. Or at best cows... (Thus Spoke Zarathustra, On the Friend)

"Woman! One-half of mankind is weak, typically sick, changeable, inconstant... she needs a religion of weakness that glorifies being weak, loving, and being humble as divine: or better, she makes the strong weak—she rules when she succeeds in overcoming the strong... Woman has always conspired with the types of decadence, the priests, against the 'powerful', the 'strong', the men-" (The Will to Power - 864, Second German edition of 1906)

Scholars of Aristotle have drawn comparisons between Aristotle's views on women and those of Nietzsche. They have argued that Nietzsche may have borrowed much of his political philosophy from the latter. [5]

Kelly Oliver and Marilyn Pearsall have even suggested that Nietzsche's philosophy cannot be understood or analyzed apart from his remarks on women. They opine that, even though Nietzsche's work has been useful in the development of some feminist theory, it cannot be considered feminist per se: "While Nietzsche challenges traditional hierarchies between mind and body, reason and irrationality, nature and culture, truth and fiction — hierarchies that have been used to degrade and exclude women — his remarks about women and his use of feminine and maternal metaphors throughout his writings confound attempts simply to proclaim Nietzsche a champion of feminism or women." [6]

Cornelia Klinger states in her book Continental Philosophy in Feminist Perspective: "Nietzsche, like Schopenhauer a prominent hater of women, at least relativizes his savage statements about woman-as-such." [7] One of Nietzsche's own statements is cited in support of this assertion:

"Whenever a cardinal problem is at stake, there speaks an unchangeable "this is I"; about man and woman, for example, a thinker cannot relearn but only finish learning–only discover ultimately how this is "settled in him." At times we find certain solutions of problems that inspire strong faith in us; some call them henceforth their "convictions." Later–we see them only as steps to self-knowledge, signposts to the problem we are–rather, to the great stupidity we are, to our spiritual fatum, to what is unteachable very "deep down".

After this abundant civility that I have just evidenced in relation to myself I shall perhaps be permitted more readily to state a few truths about "woman as such"–assuming that it is now known from the outset how very much these are after all only–my truths." (Beyond Good and Evil, Section 231)

Frances Nesbitt Oppel interprets Nietzsche's attitude towards women as part of a rhetorical strategy.

...Nietzsche's apparent misogyny is part of his overall strategy to demonstrate that our attitudes toward sex-gender are thoroughly cultural, are often destructive of our own potential as individuals and as a species, and may be changed. What looks like misogyny may be understood as part of a larger strategy whereby "woman-as-such" (the universal essence of woman with timeless character traits) is shown to be a product of male desire, a construct. [8]

Kathleen Merrow writes: "Nietzsche's metaphors of 'woman' — far from being misogynist — reveal a positive, affirmative 'woman.' His use of this metaphor radically dislocates traditional conceptions of the relationship masculine/feminine as it dislocates the 'truth' of metaphysics. I argue that the metaphor 'woman' is central to Nietzsche's attack on traditional philosophy and notions of truth." [9]

Babette Babich takes up this same quote as above, recognizing that "[a]lthough Nietzsche as generously as ever saves his commentators the labor of interpretation, the problem recurs precisely because of the nature of what he proceeds to call his truths." But instead of focusing on putative misogyny she opines:

Much more [...] must be thought to affect everything Nietzsche writes about woman. Rather than mere psychological digs and constructions, rather than a simple expression of his own misogyny, Nietzsche's philosophic expression of the nature of woman reflects and repeats the possibilities of the affirmation or denial of illusion. This is Nietzsche's understanding of truth, and to this extent Nietzsche was able to exploit his own misogyny, in style, tracing the Platonic metaphor as such. [10]

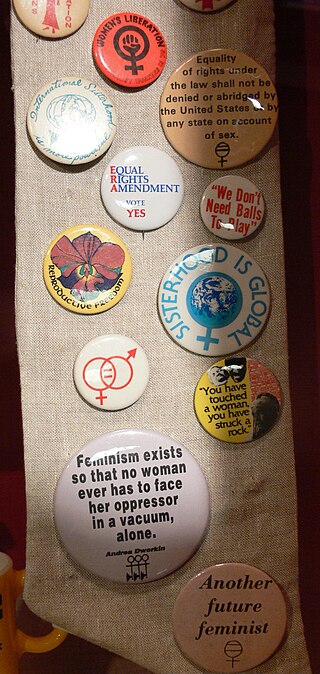

Feminist theology is a movement found in several religions, including Buddhism, Hinduism, Zoroastrianism, Sikhism, Jainism,Neopaganism, Baháʼí Faith, Judaism, Islam, Christianity, and New Thought, to reconsider the traditions, practices, scriptures, and theologies of those religions from a feminist perspective. Some of the goals of feminist theology include increasing the role of women among clergy and religious authorities, reinterpreting patriarchal (male-dominated) imagery and language about God, determining women's place in relation to career and motherhood, studying images of women in the religions' sacred texts, and matriarchal religion.

Misogyny is hatred of, contempt for, or prejudice against women or girls. It is a form of sexism that can keep women at a lower social status than men, thus maintaining the social roles of patriarchy. Misogyny has been widely practised for thousands of years. It is reflected in art, literature, human societal structure, historical events, mythology, philosophy, and religion worldwide.

Lou Andreas-Salomé was a Russian-born psychoanalyst and a well-traveled author, narrator, and essayist from a French Huguenot-German family. Her diverse intellectual interests led to friendships with a broad array of distinguished thinkers, including Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, Paul Rée, and Rainer Maria Rilke.

Luce Irigaray is a Belgian-born French feminist, philosopher, linguist, psycholinguist, psychoanalyst, and cultural theorist who examines the uses and misuses of language in relation to women. Irigaray's first and most well known book, published in 1974, was Speculum of the Other Woman (1974), which analyzes the texts of Freud, Hegel, Plato, Aristotle, Descartes, and Kant through the lens of phallocentrism. Irigaray is the author of works analyzing many thinkers, including This Sex Which Is Not One (1977), which discusses Lacan's work as well as political economy; Elemental Passions (1982) can be read as a response to Merleau‐Ponty's article “The Intertwining—The Chiasm” in The Visible and the Invisible, and in The Forgetting of Air in Martin Heidegger (1999), Irigaray critiques Heidegger's emphasis on the element of earth as the ground of life and speech and his "oblivion" or forgetting of air.

Womanism is a feminist movement, primarily championed by Black feminists, originating in the work of African American author Alice Walker in her 1983 book In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens. Walker coined the term "womanist" in the short story "Coming Apart" in 1979. Her initial use of the term evolved to envelop a spectrum of issues and perspectives facing black women and others. Walker defined "womanism" as embracing the courage, audacity, and self-assured demeanor of Black women, alongside their love for other women, themselves, and all of humanity. Since its inception by Walker, womanism has expanded to encompass various domains, giving rise to concepts such as Africana womanism and womanist theology or spirituality.

Feminist theory is the extension of feminism into theoretical, fictional, or philosophical discourse. It aims to understand the nature of gender inequality. It examines women's and men's social roles, experiences, interests, chores, and feminist politics in a variety of fields, such as anthropology and sociology, communication, media studies, psychoanalysis, political theory, home economics, literature, education, and philosophy.

Postmodern feminism is a mix of postmodernism and French feminism that rejects a universal female subject. The goal of postmodern feminism is to destabilize the patriarchal norms entrenched in society that have led to gender inequality. Postmodern feminists seek to accomplish this goal through opposing essentialism, philosophy, and universal truths in favor of embracing the differences that exist amongst women in order to demonstrate that not all women are the same. These ideologies are rejected by postmodern feminists because they believe if a universal truth is applied to all women of society, it minimizes individual experience, hence they warn women to be aware of ideas displayed as the norm in society since it may stem from masculine notions of how women should be portrayed.

Anthony Mario Ludovici MBE was a British philosopher, sociologist, social critic and polyglot. He is known as a proponent of aristocracy and anti-egalitarianism, and in the early 20th century was a leading British conservative author. He wrote on subjects including art, metaphysics, politics, economics, religion, the differences between the sexes and races, health, and eugenics.

Rosa Mayreder was an Austrian freethinker, author, painter, musician and feminist. She was the daughter of Marie and Franz Arnold Obermayer who was a wealthy restaurant operator and barkeeper.

Sarah Kofman was a French philosopher.

Babette Babich is an American philosopher who writes from a continental perspective on aesthetics, philosophy of science, especially Nietzsche's, and technology, especially Heidegger's and Günther Anders, in addition to critical and cultural theory.

Feminist theory in composition studies examines how gender, language, and cultural studies affect the teaching and practice of writing. It challenges the traditional assumptions and methods of composition studies and proposes alternative approaches that are informed by feminist perspectives. Feminist theory in composition studies covers a range of topics, such as the history and development of women's writing, the role of gender in rhetorical situations, the representation and identity of writers, and the pedagogical implications of feminist theory for writing instruction. Feminist theory in composition studies also explores how writing can be used as a tool for empowerment, resistance, and social change. Feminist theory in composition studies emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s as a response to the male-dominated field of composition and rhetoric. It has been influenced by various feminist movements and disciplines, such as second-wave feminism, poststructuralism, psychoanalysis, critical race theory, and queer theory. Feminist theory in composition studies has contributed to the revision of traditional rhetorical concepts, the recognition of diverse voices and genres, the promotion of collaborative and ethical communication, and the integration of personal and political issues in writing.

A variety of movements of feminist ideology have developed over the years. They vary in goals, strategies, and affiliations. They often overlap, and some feminists identify themselves with several branches of feminist thought.

Poststructural feminism is a branch of feminism that engages with insights from post-structuralist thought. Poststructural feminism emphasizes "the contingent and discursive nature of all identities", and in particular the social construction of gendered subjectivities.

The eternal feminine, a concept first introduced by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe at the end of his play Faust (1832), is a transcendental ideality of the feminine or womanly abstracted from the attributes, traits and behaviors of a large number of women and female figures. In Faust, these include historical, fictional, and mythological women, goddesses, and even female personifications of abstract qualities such as wisdom. As an ideal, the eternal feminine has an ethical component, which means that not all women contribute to it. Those who, for example, spread malicious gossip about other women or even just conform slavishly to their society's conventions are by definition non-contributors. Since the eternal feminine appears without explanation only in the last two lines of the 12,111-line play, it is left to the reader to work out which traits and behaviors it involves and which of the various women and female figures in the play contribute them. On these matters Goethe scholars have achieved a fair degree of consensus. The eternal feminine also has societal, cosmic and metaphysical dimensions.

Ecofeminism is a branch of feminism and political ecology. Ecofeminist thinkers draw on the concept of gender to analyse the relationships between humans and the natural world. The term was coined by the French writer Françoise d'Eaubonne in her book Le Féminisme ou la Mort (1974). Ecofeminist theory asserts a feminist perspective of Green politics that calls for an egalitarian, collaborative society in which there is no one dominant group. Today, there are several branches of ecofeminism, with varying approaches and analyses, including liberal ecofeminism, spiritual/cultural ecofeminism, and social/socialist ecofeminism. Interpretations of ecofeminism and how it might be applied to social thought include ecofeminist art, social justice and political philosophy, religion, contemporary feminism, and poetry.

Joan Stambaugh was an American philosopher and professor of philosophy at Hunter College of the City University of New York. She is known for her translations of the works of Martin Heidegger.

Misogynist terrorism is terrorism that is motivated by the desire to punish women. It is an extreme form of misogyny—the policing of women's compliance to patriarchal gender expectations. Misogynist terrorism uses mass indiscriminate violence in an attempt to avenge nonconformity with those expectations or to reinforce the perceived superiority of men.

Women Philosophers in the Long Nineteenth Century: The German Tradition is a 2021 anthology book edited by philosophers Dalia Nassar and Kristin Gjesdal, with translations by Anna C. Ezekiel. The book includes the works of nine women of the German tradition of philosophy during the long nineteenth century—a term referring to the 125-year period between the French Revolution in 1789 and the Great War in 1914. Each chapter introduces one philosopher and provides a selection of their works, including essays, letters, books, or speeches. Women Philosophers is the first published English translation for many of the works.

Michael J. McNeal (editor) (2023). Nietzsche on Women and the Eternal-Feminine: A Critique of Truth and Values. Bloomsbury Academic.

Caroline Joan S. Picart (1999). Resentment and the "Feminine" in Nietzsche's Politico-Aesthetics. Penn State University Press.

Paul Patton (1993). Nietzsche, Feminism and Political Theory. Routledge.