Motoori Norinaga was a Japanese scholar of Kokugaku active during the Edo period. He is conventionally ranked as one of the Four Great Men of Kokugaku (nativist) studies.

Karō were top-ranking samurai officials and advisors in service to the daimyōs of feudal Japan.

Kokugaku was an academic movement, a school of Japanese philology and philosophy originating during the Tokugawa period. Kokugaku scholars worked to refocus Japanese scholarship away from the then-dominant study of Chinese, Confucian, and Buddhist texts in favor of research into the early Japanese classics.

Kamo no Mabuchi, or Mabuchi of Kamo was a kokugaku scholar, poet and philologist during mid-Edo period Japan. Along with Kada no Azumamaro, Motoori Norinaga, and Hirata Atsutane, he was regarded as one of the Four Great Men of Kokugaku, and through his research into the spirit of ancient Japan he expounded on the theory of magokoro, which he held to be fundamental to the history of Japan. Independently of and alongside his contemporary Motoori Norinaga, Mabuchi is accredited with the initial discovery of Lyman's Law, governing rendaku in the Japanese language, though which would later be named after Benjamin Smith Lyman.

Keichū (契沖) was a Buddhist priest and a scholar of Kokugaku in the mid Edo period. Keichū's grandfather was a personal retainer of Katō Kiyomasa but his father was a rōnin from the Amagasaki fief. When he was 13, Keichū left home to become an acolyte of the Shingon sect, studying at Kaijō in Myōhōji, Imasato, Osaka. He subsequently attained the post of Ajari at Mount Kōya, and then became chief priest at Mandara-in in Ikutama, Osaka. It was at this time that he became friends with the poet-scholar Shimonokōbe Chōryū.

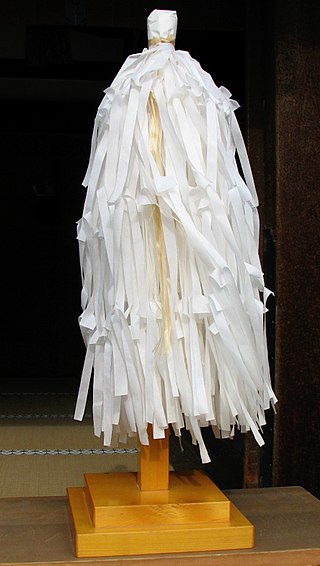

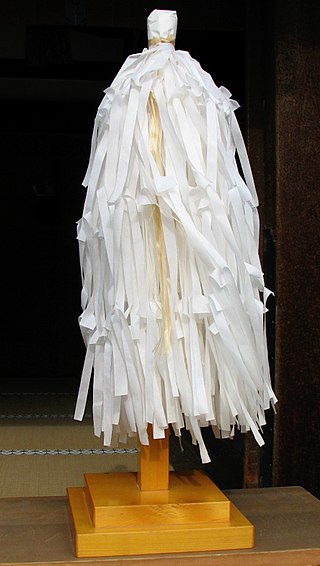

An ōnusa or simply nusa or Taima is a wooden wand traditionally used in Shinto purification rituals.

Hirata Atsutane was a Japanese scholar, conventionally ranked as one of the Four Great Men of Kokugaku (nativist) studies, and one of the most significant 19th century theologians of the Shintō religion. His literary name was Ibukinoya (気吹舎), and his primary assumed name was Daigaku. He also used the names Daikaku (大角), Gentaku (玄琢), and Genzui (玄瑞). His personal name was Hanbē (半兵衛).

Tamagushi is a form of Shinto offering made from a sakaki-tree branch decorated with shide strips of washi paper, silk, or cotton. At Japanese weddings, funerals, miyamairi and other ceremonies at Shinto shrines, tamagushi are ritually presented to the kami by parishioners, shrine maidens or kannushi priests.

Kada no Azumamaro was a poet and philologist of the early Edo period. His ideas had a germinal impact on the nativist school of National Learning in Japan.

Ko-Shintō (古神道) refers to the animistic religion of Jōmon period Japan, which is the alleged basis of modern Shinto. The search for traces of Koshintō began with the "Restoration Shinto" in the Edo period, which goal was to remove any foreign ideas and worldviews from Shinto. Some movements which claim to have discovered this primeval way of thought are Oomoto, Izumo-taishakyo.

Ame-no-Minakanushi is a deity (kami) in Japanese mythology, portrayed in the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki as the first or one of the first deities who manifested when heaven and earth came into existence.

Ubusunagami in Shinto are tutelary kami of one's birthplace.

The Four Great Men of Kokugaku are a group of Edo-period Japanese scholars recognized as the most significant figures in the Kokugaku tradition of Japanese philology, religious studies, and philosophy. They are traditionally enumerated as:

Kojiki Tōsho (古事記頭書) is a three-volume commentary on the Kojiki written by the Edo period kokugaku scholar Kamo no Mabuchi in 1757. It is also known as Kojiki Kōhon (古事記校本). It had an influence on Motoori Norinaga's Kojiki-den. It is not known to survive as a stand-alone work, but its readings were copied into several printed copies of the Kojiki, and an edition of the work that was independently annotated by Norinaga also survives.

Ōharae no Kotoba is a norito used in some Shinto rituals. It is also called Nakatomi Saimon, Nakatomi Exorcism Words, or Nakatomi Exorcism for short, because it was originally used in the Ōharae-shiki ceremony and the Nakatomi clan were solely responsible for reading it. A typical example can be found in Engishiki, Volume 8, under the title June New Year's Eve Exorcism. In general, the term "Daihourishi" refers to the words to be proclaimed to the participants of the event, while the term "Nakatomihourai" refers to a modified version of the words to be performed before the shrine or gods.

Secular Shrine Theory or Jinja hishūkyōron (神社非宗教論) was a religious policy and political theory that arose in Japan during the 19th and early 20th centuries due to the separation of church and state of the Meiji Government. It was the idea that Shinto Shrines were secular in their nature rather than religious, and that Shinto was not a religion, but rather a secular set of Japanese national traditions. This was linked to State Shinto and the idea that the state controlling and enforcing Shinto was not a violation of freedom of religion. It was subject to immense debate over this time and ultimately declined and disappeared during the Shōwa era.

Shinto is a religion native to Japan with a centuries'-long history tied to various influences in origin.

Sect Shinto refers to several independent, organized Shinto groups that were excluded by Japanese law in 1882 from government-run State Shinto. Compared to mainstream Shrine Shinto, which focuses primarily on rituals, these independent groups have a more developed theology. Many such groups are organized under the Association of Sectarian Shinto. Before World War II, Sect Shinto consisted of 13 denominations, which were referred to as the 13 Shinto schools. Since then, there have been additions to and withdrawals from membership.

Confucian Shinto, also known as Juka Shintō (儒家神道) in Japanese, is a syncretic religious tradition that combines elements of Confucianism and Shinto. It originated in Japan during the Edo period (1603–1868), and is sometimes referred to as "Neo-Confucian Shinto"

Hirata Kanetane was a Japanese scholar of kokugaku. He studied under Hirata Atsutane, and later became his adopted son and heir.