Onmyōdō is a technique that uses knowledge of astronomy and calendars to divine good fortune in terms of date, time, direction and general personnel affairs, originating from the philosophy of the yin-yang and the five elements.

Ubusunagami in Shinto are tutelary kami of one's birthplace.

The Niiname-sai is a Japanese harvest ritual.

Takamimusubi is a god of agriculture in Japanese mythology, who was the second of the first beings to come into existence.

Kukunochi is the kami of trees, the kami is also called Ki-no-kami, or Kuku-no-shi. He is the brother of Ōyamatsumi, Shimatsuhiko, and Watatsumi.

Kamimusubi (神産巣日), also known as Kamimusuhi among other variants, is a kami and god of creation in Japanese mythology. They are a hitorigami, and the third of the first three kami to come into existence (Kotoamatsukami), alongside Ame-no-Minakanushi and Takamimusubi, forming a trio at the beginning of all creation. The name is composed of kami, denoting deity, and musubi, meaning "effecting force of creation".

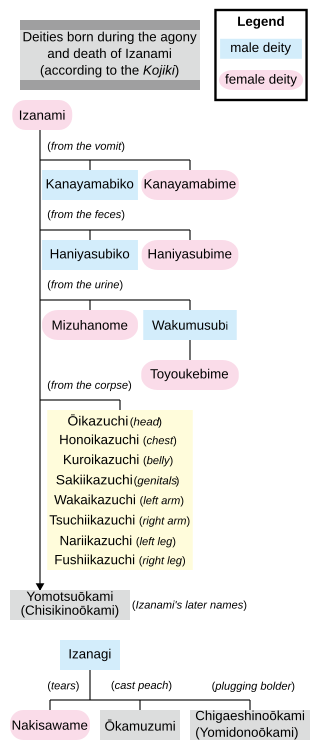

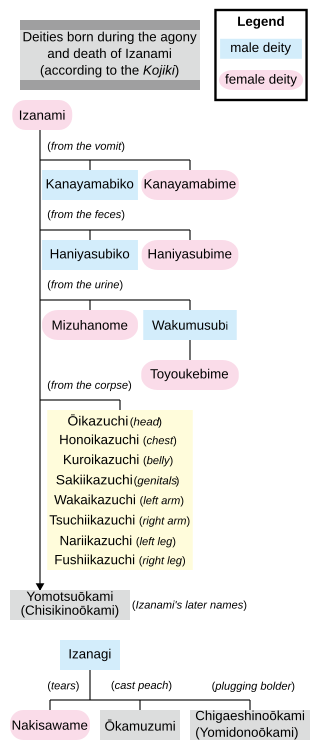

Wakumusubi (和久産巣日神) is a kami of agriculture. In many versions, he was born from the urine of Izanami when she died. Another version of the Nihon Shoki states he was a child of Kagutsuchi and Haniyasu-hime.

Oshirasama is a tutelary deity of the home in Japanese folklore. It is believed that when oshirasama is in a person's home, one cannot eat meat and only women are allowed to touch it.

Mizuhanome is a divinity of water in Japanese mythology. She was born from the urine of Izanami.

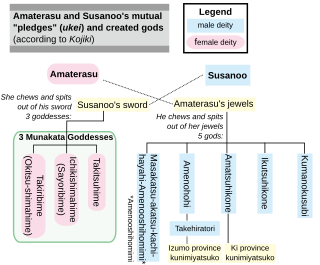

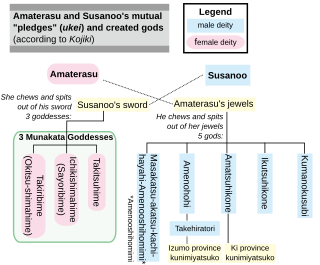

Kumanokusubi is a God in Japanese mythology. He is the fifth son of Amaterasu.

Secular Shrine Theory or Jinja hishūkyōron (神社非宗教論) was a religious policy and political theory that arose in Japan during the 19th and early 20th centuries due to the separation of church and state of the Meiji Government. It was the idea that Shinto Shrines were secular in their nature rather than religious, and that Shinto was not a religion, but rather a secular set of Japanese national traditions. This was linked to State Shinto and the idea that the state controlling and enforcing Shinto was not a violation of freedom of religion. It was subject to immense debate over this time and ultimately declined and disappeared during the Shōwa era.

A katashiro (形代) is a kind of yorishiro where a kami is said to enter which has a human form. In Shinto rituals and folk customs, dolls are used as human substitutes to transfer sins and impurities during exorcisms. They are usually made of paper or thin boards. After the exorcism, they are thrown into the river or sea, or burned. During Hinamatsuri in March, people use these dolls as nademono (撫で物) to stroke the parts of their bodies that are not in good shape, and then cast them into the river or sea to pray for the growth of their children.

Kugatachi (盟神探湯) is a kind of trial by ordeal that was conducted in ancient Japan. It was done through exposure to boiling water and it is believed that innocent people would not be scalded and guilty people would be scalded due to divine intervention by kami.

Sect Shinto refers to several independent organized Shinto groups that were excluded by Japanese law in 1882 from government-run State Shinto. These independent groups have more developed belief systems than mainstream Shrine Shinto, which focuses more on rituals. Many such groups are organized into the Association of Sectarian Shinto. Before World War II, Sect Shinto consisted of 13 denominations, which were referred to as the 13 Shinto schools. Since then, there have been additions and withdrawals of membership.

Shinto Taiseikyo (神道大成教) is one of the thirteen Shinto sects. It was founded by Hirayama Seisai (1815–1890) and is considered a form of Confucian Shinto.

The National Association of Shinto Priests was a Japanese religious association that promoted the prosperity of Shinto shrines and the improvement and development of Kannushi. It was founded in 1898 to expound the Kokutai ideology. It was dissolved in 1946 with the formation of the religious corporation, which became one of the predecessor organizations of the Association of Shinto Shrines.

Fukko Shintō is a movement within Shinto that was advocated by Japanese scholars during the Edo period. It attempted to reject Buddhist and Confucian influence on Shinto and return to a native Japanese tradition based on Koshinto.

The Great Teaching Institute was an organization under the Ministry of Religion in the Empire of Japan.

Hakushu 拍手 (神道) is a word used to refer to ceremonial clapping in Shinto. It is also known as Kashiwade.

Nitta Kuniteru (新田邦光) (1829–1902) was a founder of a Sect Shinto group. He founded Shinto Shusei in 1849. He read the Analects at age 9. He founded the sect at age twenty, and considered Japanese people to be descendants of deities. He considered allegiance to the Emperor of Japan to be central to his philosophy; he was a supporter of Sonnō jōi but supported the Boshin Rebellion and the Meiji Restoration later. He managed to gain independence for the sect in 1876.