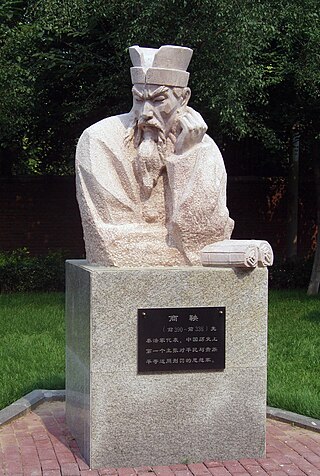

Imaginary portrait of Xunzi, Qing dynasty (1636–1912), Palace Museum | |

| Born | c. 310 BCE |

| Died | After c. 238 BCE (aged mid 70s) |

| Era | Hundred Schools of Thought (Ancient philosophy) |

| Region | Chinese philosophy |

| School | Confucianism |

| Notable students | Han Fei, Li Si |

Main interests | Ritual (Li), Human nature, Education, Music, Heaven, Dao, Rectification of names |

Xunzi notes that despite Qin's achievements, it is "filled with trepidation. Despite its complete and simultaneous possession of all these numerous attributes, if one weights Qin by the standard of the solid achievements of True Kingship, then the vast degree to which it fails to reach the ideal is manifest. Why is that? It is that it is dangerously lacking in Ru [Confucian] scholars"

Xunzi's writings suggest that after leaving Qi he visited Qin, possibly from 265 BCE to 260 BCE. [22] [31] He aimed to convert the state's leaders to follow his philosophy of leadership, a task which proved difficult because of the strong hold that Shang Yang's Legalist sentiments had there. [31] In a conversation with the Qin official Fan Sui, Xunzi praised much of the state's achievements, officials and governmental organizations. [32] Still, Xunzi found issues with the state, primarily its lack of Confucian scholars and the fear it inspires, which Xunzi claimed would result in the surrounding states uniting up against. [33] Xunzi then met with King Zhaoxiang, arguing that Qin's lack of Confucian scholars and educational encouragement would be detrimental to the state's future. [33] The king was unconvinced by Xunzi's persuasion, and did not offer him a post in his court. [34]

In around 260 BCE, Xunzi returned to his native Zhao, where he debated military affairs with Lord Linwu (臨武君) in the court of King Xiaocheng of Zhao. [35] He remained in Zhao until c. 255 BCE. [22]

In 240 BCE Lord Chunshen, the prime minister of Chu, invited him to take a position as Magistrate of Lanling (蘭陵令), which he initially refused and then accepted. However, Lord Chunshen was assassinated In 238 BCE by a court rival and Xunzi subsequently lost his position. He retired, remained in Lanling, a region in what is today's southern Shandong province, for the rest of his life and was buried there. The year of his death is unknown, though if he lived to see the ministership of his student Li Si, as recounted, he would have lived into his nineties, dying shortly after 219 BCE. [22] [36]

Philosophy

| Xunzi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 荀況 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Confucianism |

|---|

|

Human nature – xing

The best known and most cited section of the Xunzi is chapter 23, "Human Nature is Evil". Human nature, known as xing (性), was a topic which Confucius commented on somewhat ambiguously, leaving much room for later philosophers to expand upon. [37] Xunzi does not appear to know about Shang Yang, [38] but can be compared with him. While Shang Yang believed that people were selfish, [39] Xunzi believed that humanity's inborn tendencies were evil and that ethical norms had been invented to rectify people. His variety of Confucianism therefore has a darker, more pessimistic flavor than the optimistic Confucianism of Mencius, who tended to view humans as innately good. Like most Confucians, however, he believed that people could be refined through education and ritual. [40] [41]

Now, since human nature is evil, it must await the instructions of a teacher and the model before it can be put aright, and it must obtain ritual principles and a sense of moral right before it can become orderly.

Both Mencius and Xunzi believed in human nature and both believed it was possible to become better, but some people refused it. [43] Mencius saw Xing as more related to an ideal state and Xunzi saw it more as a starting state. [43]

Even though Mencius had already died when the book was written, the chapter is written like a conversation between the two philosophers. Xunzi's ideas about becoming a good person were more complex than Mencius's. He believed that people needed to change their nature, not just give up on it. Some people thought Xunzi's ideas were strange, but new discoveries suggest that it might have actually been Mencius who had unusual ideas about human nature. [43]

The chapter is called "Human Nature is Evil," but that's not the whole story. Xunzi thought that people could improve themselves by learning good habits and manners, which he called "artifice." (偽) He believed that people needed to transform their nature to become good. This could be done by learning from a teacher and following rituals and morals. [43]

Even though some people doubt if the chapter is real, it's an important part of Xunzi's philosophy. People still talk about it today and think about the differences between Xunzi and Mencius's ideas about human nature and how to become a better person. [43]

Xunzi only stated that the "heart" can observe reason, that is, it can distinguish between right and wrong, good and evil, [44] but it is not the source of value. So where does the standard come from? According to Xunzi's theory of evil human nature, morality will ultimately become a tool of external value used to maintain social stability and appeal to authoritarianism. Mencius' theory of good human nature, on the other hand, states that humans are inherently good and we have an internal value foundation (the Four Beginnings).

Music – yue

Music is discussed throughout the Xunzi, particularly in chapter 20, the "Discourse on Music" (Yuelun; 樂論). [45] Much of the Xunzi's sentiments on music are directed towards Mozi, who largely disparaged music. [46] Mozi held that music provides no basic needs and is a waste of resources and money. [47] Xunzi presents a comprehensive argument in opposition, stating that certain music provides joy, which is indeed essential to human wellbeing. [48] Music and joy are respectively translated as yue and le, and their connection in Xunzi's time may explain why both words share the same Chinese character: 樂. [48] Xunzi also points out the use of music for social harmony:

故樂在宗廟之中,君臣上下同聽之,則莫不和敬;閨門之內,父子兄弟同聽之,則莫不和親;鄉里族長之中,長少同聽之,則莫不和順。

Hence, when music is performed within the ancestral temple, lord and subject, high and low, listen to the music together and are united in feelings of reverence. When music is played in the private quarters of the home, father and son, elder and younger brother, listen to it together and are united in feelings of close kinship. When it is played in village meetings or clan halls, old and young listen to the music together and are joined in obedience.

Many commentators have noted the similarities between the reasons for Xunzi's promotion of music and those of ancient Greek philosophers. [45] [50]

Gentleman – junzi

Ultimately, he refused to admit theories of state and administration apart from ritual and self-cultivation, arguing for the gentleman, rather than the measurements promoted by the Legalists, as the wellspring of objective criterion. His ideal gentleman (junzi) king and government, aided by a class of erudites (Confucian scholars), are similar to that of Mencius, but without the tolerance of feudalism since he rejected hereditary titles and believed that an individual's status in the social hierarchy should be determined only by their own merit. [40]