Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China, and is variously described as a tradition, philosophy, religion, theory of government, or way of life. Confucianism developed from teachings of the Chinese philosopher Confucius (551–479 BC), during a time that was later referred to as the Hundred Schools of Thought era. Confucius considered himself a transmitter of cultural values inherited from the Xia (c. 2070–1600 BC), Shang (c. 1600–1046 BC), and Western Zhou (c. 1046–771 BC) dynasties. Confucianism was suppressed during the Legalist and autocratic Qin dynasty (221–206 BC), but survived. During the Han dynasty, Confucian approaches edged out the "proto-Taoist" Huang–Lao as the official ideology, while the emperors mixed both with the realist techniques of Legalism.

Confucius, born Kong Qiu (孔丘), was a Chinese philosopher of the Spring and Autumn period who is traditionally considered the paragon of Chinese sages. Much of the shared cultural heritage of the Sinosphere originates in the philosophy and teachings of Confucius. His philosophical teachings, called Confucianism, emphasized personal and governmental morality, harmonious social relationships, righteousness, kindness, sincerity, and a ruler's responsibilities to lead by virtue.

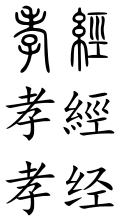

The Chinese classics or canonical texts are the works of Chinese literature authored prior to the establishment of the imperial Qin dynasty in 221 BC. Prominent examples include the Four Books and Five Classics in the Neo-Confucian tradition, themselves an abridgment of the Thirteen Classics. The Chinese classics used a form of written Chinese consciously imitated by later authors, now known as Classical Chinese. A common Chinese word for "classic" literally means 'warp thread', in reference to the techniques by which works of this period were bound into volumes.

Mencius was a Chinese Confucian philosopher, often described as the Second Sage (亞聖) to reflect his traditional esteem relative to Confucius himself. He was part of Confucius's fourth generation of disciples, inheriting his ideology and developing it further. Living during the Warring States period, he is said to have spent much of his life travelling around the states offering counsel to different rulers. Conversations with these rulers form the basis of the Mencius, which would later be canonised as a Confucian classic.

The Great Learning or Daxue was one of the "Four Books" in Confucianism attributed to one of Confucius' disciples, Zengzi. The Great Learning had come from a chapter in the Book of Rites which formed one of the Five Classics. It consists of a short main text of the teachings of Confucius transcribed by Zengzi and then ten commentary chapters supposedly written by Zengzi. The ideals of the book were attributed to Confucius, but the text was written by Zengzi after his death.

The Analects, also known as the Sayings of Confucius, is an ancient Chinese philosophical text composed of sayings and ideas attributed to Confucius and his contemporaries, traditionally believed to have been compiled by his followers.

Filial piety is the virtue of exhibiting love and respect for one's parents, elders, and ancestors, particularly within the context of Confucian, Chinese Buddhist, and Daoist ethics. The Confucian Classic of Filial Piety, thought to be written around the late Warring States-Qin-Han period, has historically been the authoritative source on the Confucian tenet of filial piety. The book—a purported dialogue between Confucius and his student Zengzi—is about how to set up a good society using the principle of filial piety. Filial piety is central to Confucian role ethics.

Zeng Shen, better known as Zengzi, courtesy name Ziyu, was a Chinese philosopher and disciple of Confucius. He later taught Zisi, the grandson of Confucius, who was in turn the teacher of Mencius, thus beginning a line of transmitters of orthodox Confucian traditions. He is revered as one of the Four Sages of Confucianism.

The word junzi is a Chinese philosophical term often translated as "gentleman," "superior person", or "noble man." Since the characters are overtly gendered, the term is frequently translated as "gentleman"; gentry and distinguished/moral person are common gender-neutral translations. Junzi is employed in the "Classic of Changes", attributed traditionally to the Duke Wen of Zhou, and by Confucius in his works to describe the ideal human being.

Yan Jun, courtesy name Mancai, was an official of the state of Eastern Wu during the Three Kingdoms period of China.

The Four Books and Five Classics are authoritative and important books associated with Confucianism, written before 300 BC. They are traditionally believed to have been either written, edited or commented by Confucius or one of his disciples. Starting in the Han dynasty, they became the core of the Chinese classics on which students were tested in the Imperial examination system.

The Twenty-four Filial Exemplars, also translated as The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety, is a classic text of Confucian filial piety written by Guo Jujing (郭居敬) during the Yuan dynasty (1260–1368). The text was extremely influential in the medieval Far East and was used to teach Confucian moral values.

The Thirteen Classics is a term for the group of thirteen classics of Confucian tradition that became the basis for the Imperial Examinations during the Song dynasty and have shaped much of East Asian culture and thought. It includes all of the Four Books and Five Classics but organizes them differently and includes the Classic of Filial Piety and Erya.

Jing is a concept in Chinese philosophy which is typically translated as "reverence". It is often used by Confucius in the term gōngjìng (恭敬), meaning "respectful reverence". For Confucians, jìng requires yì, or righteousness, and a proper observation of rituals. To have jìng is vitally important in the maintenance of xiào, or filial piety.

Lu Ji (188–219), courtesy name Gongji, was a Chinese politician and scholar serving under the warlord Sun Quan in the late Eastern Han dynasty of China. He was also one of the 24 Filial Exemplars.

Min Sun, also known by his courtesy name Ziqian, was one of the most prominent disciples of Confucius. Confucius considered Min his second best disciple after Yan Hui, and commended him for his filial piety. His legend is included in the Confucian text The Twenty-four Filial Exemplars.

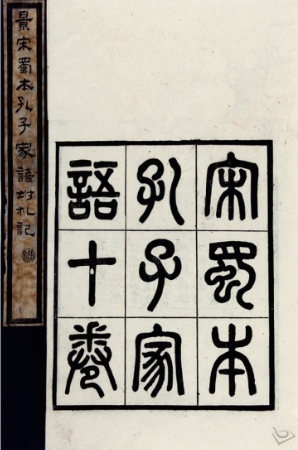

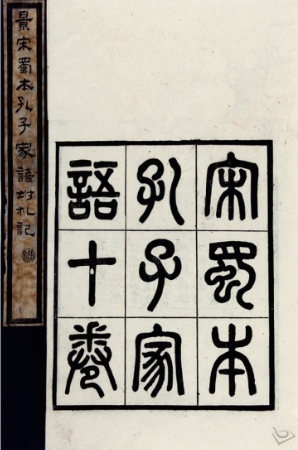

The Kongzi Jiayu, translated as The School Sayings of Confucius or Family Sayings of Confucius, is a collection of sayings of Confucius (Kongzi), written as a supplement to the Analects (Lunyu).

Yuan Xian, courtesy name Zisi or Yuan Si, was a Chinese philosopher who was a major disciple of Confucius. Classic Chinese sources stated he was modest and incorruptible, and adhered strictly to the teachings of Confucius despite living in abject poverty.

Zeng Dian, courtesy name Zixi, also known as Zeng Xi, was one of the earliest disciples of Confucius. He is known for a passage in the Analects in which he expressed his ambition as no more than being content with daily life. He was the father of Zeng Shen, or Master Zeng, one of the most prominent disciples of Confucius.

Xué Ér (學而) is the first book of the Analects of Confucius. According to Zhu Xi, a Confucian philosopher in the 12th century, the book Xue Er is the base of moral improvement because it touches upon the basic principles of being a "gentleman".