| Part of a series on |

| Taoism |

|---|

|

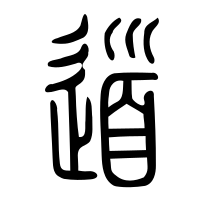

"Tao" is written with the Chinese character 道 using both traditional and simplified characters. The traditional graphical interpretation of 道 dates back to the Shuowen Jiezi dictionary published in 121 CE, which describes it as a rare "compound ideogram" or "ideographic compound". According to the Shuowen Jiezi, 道 combines the 'go' radical 辶 (a variant of 辵) with 首; 'head'. This construction signified a "head going" or "leading the way".

"Tao" is graphically distinguished between its earliest nominal meaning of 'way', 'road', 'path', and the later verbal sense of 'say'. It should also be contrasted with 導; 'lead the way', 'guide', 'conduct', 'direct'. The simplified character 导 for 導 has 巳; '6th of the 12 Earthly Branches ' in place of 道.

The earliest written forms of "Tao" are bronzeware script and seal script characters from the Zhou dynasty (1045–256 BCE) bronzes and writings. These ancient forms more clearly depict the 首; 'head' element as hair above a face. Some variants interchange the 'go' radical 辵 with 行; 'go', 'road', with the original bronze "crossroads" depiction written in the seal character with two 彳 and 亍; 'footprints'.

Bronze scripts for 道 occasionally include an element of 手; 'hand' or 寸; 'thumb', 'hand', which occurs in 導; 'lead'. The linguist Peter A. Boodberg explained,

This "tao with the hand element" is usually identified with the modern character 導tao < d'ôg, 'to lead,', 'guide', 'conduct', and considered to be a derivative or verbal cognate of the noun tao, "way," "path." The evidence just summarized would indicate rather that "tao with the hand" is but a variant of the basic tao and that the word itself combined both nominal and verbal aspects of the etymon. This is supported by textual examples of the use of the primary tao in the verbal sense "to lead" (e. g., Analects 1.5; 2.8) and seriously undermines the unspoken assumption implied in the common translation of Tao as "way" that the concept is essentially a nominal one. Tao would seem, then, to be etymologically a more dynamic concept than we have made it translation-wise. It would be more appropriately rendered by "lead way" and "lode" ("way," "course," "journey," "leading," "guidance"; cf. "lodestone" and "lodestar"), the somewhat obsolescent deverbal noun from "to lead." [37]

These Confucian Analects citations of dao verbally meaning 'to guide', 'to lead' are: "The Master said, 'In guiding a state of a thousand chariots, approach your duties with reverence and be trustworthy in what you say" and "The Master said, 'Guide them by edicts, keep them in line with punishments, and the common people will stay out of trouble but will have no sense of shame." [38]

Phonology

In modern Standard Chinese, 道's two primary pronunciations are tonally differentiated between falling tone dào; 'way', 'path' and dipping tone dǎo; 'guide', 'lead' (usually written as 導).

Besides the common specifications 道; dào; 'way' and 道; dǎo (with variant 導; 'guide'), 道 has a rare additional pronunciation with the level tone, dāo, seen in the regional chengyu 神神道道; shénshendāodāo; 'odd', 'bizarre', a reduplication of 道 and 神; shén; 'spirit', 'god' from northeast China.

In Middle Chinese (c. 6th–10th centuries CE) tone name categories, 道 and 導 were 去聲; qùshēng; 'departing tone' and 上聲; shǎngshēng; 'rising tone'. Historical linguists have reconstructed MC道; 'way' and 導; 'guide' as d'âu- and d'âu (Bernhard Karlgren), [39] dau and dau [40] daw' and dawh, [41] dawX and daws (William H. Baxter), [42] and dâuB and dâuC. [43]

In Old Chinese (c. 7th–3rd centuries BCE) pronunciations, reconstructions for 道 and 導 are *d'ôg (Karlgren), *dəw (Zhou), *dəgwx and *dəgwh, [44] *luʔ, [42] and *lûʔ and *lûh. [43]

Semantics

The word 道 has many meanings. For example, the Hanyu Da Zidian dictionary defines 39 meanings for 道; dào and 6 for 道; dǎo. [45]

John DeFrancis's Chinese-English dictionary gives twelve meanings for 道; dào, three for 道; dǎo, and one for 道; dāo. Note that brackets clarify abbreviations and ellipsis marks omitted usage examples.

2dào道 N. [ noun ] road; path ◆M. [nominal measure word ] ① (for rivers/topics/etc.) ② (for a course (of food); a streak (of light); etc.) ◆V. [ verb ] ① say; speak; talk (introducing direct quote, novel style) ... ② think; suppose ◆B.F. [bound form, bound morpheme ] ① channel ② way; reason; principle ③ doctrine ④ Daoism ⑤ line ⑥〈hist.〉 [history] ⑦ district; circuit canal; passage; tube ⑧ say (polite words) ... See also 4dǎo, 4dāo

4dǎo导/道[導/- B.F. [bound form] ① guide; lead ... ② transmit; conduct ... ③ instruct; direct ...

4dāo道 in shénshendāodāo ... 神神道道 R.F. [ reduplicated form] 〈topo.〉[non-Mandarin form] odd; fantastic; bizarre [46]

Dao, starting from the Song dynasty, also referred to an ideal in Chinese landscape paintings that artists sought to live up to by portraying "nature scenes" that reflected "the harmony of man with his surroundings." [47]

Etymology

The etymological linguistic origins of dao "way; path" depend upon its Old Chinese pronunciation, which scholars have tentatively reconstructed as *d'ôg, *dəgwx, *dəw, *luʔ, and *lûʔ.

Boodberg noted that the shou首 "head" phonetic in the dao道 character was not merely phonetic but "etymonic", analogous with English to head meaning "to lead" and "to tend in a certain direction," "ahead," "headway".

Paronomastically, tao is equated with its homonym 蹈 tao < d'ôg, "to trample," "tread," and from that point of view it is nothing more than a "treadway," "headtread," or "foretread "; it is also occasionally associated with a near synonym (and possible cognate) 迪 ti < d'iôk, "follow a road," "go along," "lead," "direct"; "pursue the right path"; a term with definite ethical overtones and a graph with an exceedingly interesting phonetic, 由 yu < djôg," "to proceed from." The reappearance of C162 [辶] "walk" in ti with the support of C157 [⻊] "foot" in tao, "to trample," "tread," should perhaps serve us as a warning not to overemphasize the headworking functions implied in tao in preference to those of the lower extremities. [48]

Victor H. Mair proposes a connection with Proto-Indo-European drogh, supported by numerous cognates in Indo-European languages, as well as semantically similar Semitic Arabic and Hebrew words.

The archaic pronunciation of Tao sounded approximately like drog or dorg. This links it to the Proto-Indo-European root drogh (to run along) and Indo-European dhorg (way, movement). Related words in a few modern Indo-European languages are Russian doroga (way, road), Polish droga (way, road), Czech dráha (way, track), Serbo-Croatian draga (path through a valley), and Norwegian dialect drog (trail of animals; valley). .... The nearest Sanskrit (Old Indian) cognates to Tao (drog) are dhrajas (course, motion) and dhraj (course). The most closely related English words are "track" and "trek", while "trail" and "tract" are derived from other cognate Indo-European roots. Following the Way, then, is like going on a cosmic trek. Even more unexpected than the panoply of Indo-European cognates for Tao (drog) is the Hebrew root d-r-g for the same word and Arabic t-r-q, which yields words meaning "track, path, way, way of doing things" and is important in Islamic philosophical discourse. [49]

Axel Schuessler's etymological dictionary presents two possibilities for the tonal morphology of dào道 "road; way; method" < Middle Chinese dâuB < Old Chinese *lûʔ and dào道 or 導 "to go along; bring along; conduct; explain; talk about" < Middle dâuC < Old *lûh. [50] Either dào道 "the thing which is doing the conducting" is a Tone B (shangsheng上聲 "rising tone") "endoactive noun" derivation from dào導 "conduct", or dào導 is a Later Old Chinese (Warring States period) "general tone C" (qusheng去聲 "departing tone") derivation from dào道 "way". [51] For a possible etymological connection, Schuessler notes the ancient Fangyan dictionary defines yu < *lokh裕 and lu < *lu猷 as Eastern Qi State dialectal words meaning dào < *lûʔ道 "road".

Other languages

Many languages have borrowed and adapted "Tao" as a loanword.

In Chinese, this character 道 is pronounced as Cantonese dou6 and Hokkian to7. In Sino-Xenic languages, 道 is pronounced as Japanese dō, tō, or michi; Korean do or to; and Vietnamese đạo.

Since 1982, when the International Organization for Standardization adopted Pinyin as the standard romanization of Chinese, many Western languages have changed from spelling this loanword tao in national systems (e.g., French EFEO Chinese transcription and English Wade–Giles) to dao in Pinyin.

The tao/dao "the way" English word of Chinese origin has three meanings, according to the Oxford English Dictionary .

1. a. In Taoism, an absolute entity which is the source of the universe; the way in which this absolute entity functions.

1. b. = Taoism, taoist

2. In Confucianism and in extended uses, the way to be followed, the right conduct; doctrine or method.

The earliest recorded usages were Tao (1736), Tau (1747), Taou (1831), and Dao (1971).

The term "Taoist priest" (道士; Dàoshì), was used already by the Jesuits Matteo Ricci and Nicolas Trigault in their De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas , rendered as Tausu in the original Latin edition (1615), [note 5] and Tausa in an early English translation published by Samuel Purchas (1625). [note 6]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Chinese :道; pinyin :dào( ⓘ )

- ↑ Tao Te Ching, Chapter 1. "It is from the unnamed Tao

That Heaven and Earth sprang;

The named is but

The Mother of the ten thousand creatures." - ↑ I Ching, Ta Chuan (Great Treatise). "The kind man discovers it and calls it kind;

the wise man discovers it and calls it wise;

the common people use it every day

and are not aware of it." - ↑ Water is soft and flexible, yet possesses an immense power to overcome obstacles and alter landscapes, even carving canyons with its slow and steady persistence. It is viewed as a reflection of, or close in action to, the Tao. The Tao is often expressed as a sea or flood that cannot be dammed or denied. It flows around and over obstacles like water, setting an example for those who wish to live in accord with it. [13]

- ↑ De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas suscepta ab Societate Jesu , Book One, Chapter 10, p. 125. Quote: "sectarii quidam Tausu vocant". Chinese gloss in Pasquale M. d' Elia, Matteo Ricci. Fonti ricciane: documenti originali concernenti Matteo Ricci e la storia delle prime relazioni tra l'Europa e la Cina (1579-1615), Libreria dello Stato, 1942; can be found by searching for "tausu". Louis J. Gallagher (China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journals of Matteo Ricci; 1953), apparently has a typo (Taufu instead of Tausu) in the text of his translation of this line (p. 102), and Tausi in the index (p. 615)

- ↑ A discourse of the Kingdome of China, taken out of Ricius and Trigautius, containing the countrey, people, government, religion, rites, sects, characters, studies, arts, acts ; and a Map of China added, drawne out of one there made with Annotations for the understanding thereof (excerpts from De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas , in English translation) in Purchas his Pilgrimes , Volume XII, p. 461 (1625). Quote: "... Lauzu ... left no Bookes of his Opinion, nor seemes to have intended any new Sect, but certaine Sectaries, called Tausa, made him the head of their sect after his death..." Can be found in the full text of "Hakluytus posthumus" on archive.org.

References

Citations

- ↑ Zai (2015), p. [ page needed ].

- ↑ DeFrancis (1996), p. 113.

- ↑ LaFargue (1992), pp. 245–247.

- ↑ Chan (1963), p. 136.

- ↑ Hansen (2000), p. 206.

- ↑ Liu (1981), pp. 1–3.

- ↑ Liu (1981), pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Cane (2002), p. 13.

- ↑ Keller (2003), p. 289.

- ↑ LaFargue (1994), p. 283.

- 1 2 Carlson et al. (2010), p. 704.

- ↑ Jian-guang (2019), pp. 754, 759.

- ↑ Ch'eng & Cheng (1991), pp. 175–177.

- ↑ Wright (2006), p. 365.

- ↑ Carlson et al. (2010), p. 730.

- ↑ "Taoism". education.nationalgeographic.org. Retrieved 2024-05-29.

- ↑ Maspero (1981), p. 32.

- ↑ Bodde & Fung (1997), pp. 99–101.

- ↑ Waley (1958), p. [ page needed ].

- ↑ Kohn (1993), p. 11.

- 1 2 Kohn (1993), pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Kohn (1993), p. 12.

- ↑ Fowler (2005), pp. 5–7.

- ↑ "Daoism". Encarta . Microsoft. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28.

- ↑ Moeller (2006), pp. 133–145.

- ↑ Fowler (2005), pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Mair (2001), p. 174.

- ↑ Stark (2007), p. 259.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Taylor & Choy (2005), p. 589.

- ↑ Harl (2023), p. 272.

- ↑ Dumoulin (2005), pp. 63–65.

- ↑ Hershock (1996), pp. 67–70.

- ↑ Ni (2023), p. 168.

- ↑ Lewis, C.S. The Abolition of Man . p. 18.

- ↑ Damascene (2012), p. [ page needed ].

- ↑ Zheng (2017), p. 187.

- ↑ Boodberg (1957), p. 599.

- ↑ Lau (1979), p. 59, 1.5; p. 63, 2.8.

- ↑ Karlgren (1957), p. [ page needed ].

- ↑ Zhou (1972), p. [ page needed ].

- ↑ Pulleyblank (1991), p. 248.

- 1 2 Baxter (1992), pp. 753.

- 1 2 Schuessler (2007), p. [ page needed ].

- ↑ Li (1971), p. [ page needed ].

- ↑ Hanyu Da Zidian (1989), pp. 3864–3866.

- ↑ DeFrancis (2003), pp. 172, 829.

- ↑ Meyer (1994), p. 96.

- ↑ Boodberg (1957), p. 602.

- ↑ Mair (1990), p. 132.

- ↑ Schuessler (2007), p. 207.

- ↑ Schuessler (2007), pp. 48–41.

Works cited

- Baxter, William H. (1992). A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-110-12324-1.

- Bodde, Derk; Fung, Yu-Lan (1997). A short history of Chinese philosophy. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-684-83634-3.

- Boodberg, Peter A. (1957). "Philological Notes on Chapter One of the Lao Tzu". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 20 (3/4): 598–618. doi:10.2307/2718364. JSTOR 2718364.

- Cane, Eulalio Paul (2002). Harmony: Radical Taoism Gently Applied. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 1-4122-4778-0.

- Carlson, Kathie; Flanagin, Michael N.; Martin, Kathleen; Martin, Mary E.; Mendelsohn, John; Rodgers, Priscilla Young; Ronnberg, Ami; Salman, Sherry; Wesley, Deborah A. (2010). Arm, Karen; Ueda, Kako; Thulin, Anne; Langerak, Allison; Kiley, Timothy Gus; Wolff, Mary (eds.). The Book of Symbols: Reflections on Archetypal Images. Köln: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8365-1448-4.

- Chang, Stephen T. (1985). The Great Tao. Tao Publishing, imprint of Tao Longevity. ISBN 0-942196-01-5.

- Ch'eng, Chung-Ying; Cheng, Zhongying (1991). New dimensions of Confucian and Neo-Confucian philosophy. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-0283-5.

- Chan, Wing-tsit (1963). A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy. Princeton. ISBN 0-691-01964-9.

- Damascene, Hieromonk (2012). Christ the Eternal Tao (6th ed.). Valaam Books.

- DeFrancis, John, ed. (1996). ABC Chinese-English Dictionary: Alphabetically Based Computerized (ABC Chinese Dictionary). University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1744-3.

- DeFrancis, John, ed. (2003). ABC Chinese-English Comprehensive Dictionary. University of Hawaii Press.

- Dumoulin, Henrik (2005). Zen Buddhism: a History: India and China. Translated by Heisig, James; Knitter, Paul. World Wisdom. ISBN 0-941532-89-5.

- Fowler, Jeaneane (2005). An introduction to the philosophy and religion of Taoism: pathways to immortality. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 1-84519-085-8.

- Hansen, Chad D. (2000). A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought: A Philosophical Interpretation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513419-2.

- Hanyu Da Zidian (in Chinese). Vol. 6. Wuhan: Hubei Cishu Chubanshe. 1989. ISBN 978-7-5403-0022-7.

- Harl, Kenneth W. (2023). Empires of the Steppes: A History of the Nomadic Tribes Who Shaped Civilization. United States: Hanover Square Press. ISBN 978-1-335-42927-8.

- Hershock, Peter (1996). Liberating intimacy: enlightenment and social virtuosity in Ch'an Buddhism. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-2981-4.

- Jian-guang, Wang (December 2019). "Water Philosophy in Ancient Society of China: Connotation, Representation, and Influence" (PDF). Philosophy Study. 9 (12): 750–760.

- Karlgren, Bernhard (1957). Grammata Serica Recensa. Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities.

- Keller, Catherine (2003). The Face of the Deep: A Theology of Becoming. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25648-8.

- Kirkland, Russell (2004). Taoism: The Enduring Tradition. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-26321-4.

- Kohn, Livia (1993). The Taoist experience. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-1579-1.

- Komjathy, Louis (2008). Handbooks for Daoist Practice. Hong Kong: Yuen Yuen Institute.

- LaFargue, Michael (1994). Tao and Method: A Reasoned Approach to the Tao Te Ching. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-1601-1.

- LaFargue, Michael (1992). The tao of the Tao te ching: a translation and commentary. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-0986-4.

- Lau (1979). The Analects (Lun yu). Translated by Lau, D. C. Penguin.

- Li, Fanggui (1971). "Shanggu yin yanjiu" 上古音研究. Tsinghua Journal of Chinese Studies (in Chinese). 9: 1–61.

- Liu, Da (1981). The Tao and Chinese culture . Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-7100-0841-4.

- Mair, Victor H. (1990). Tao Te Ching: The Classic Book of Integrity and the Way, by Lao Tzu; an entirely new translation based on the recently discovered Ma-wang-tui manuscripts. Bantam Books.

- Mair, Victor H. (2001). The Columbia History of Chinese Literature. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-10984-9.

- Martinson, Paul Varo (1987). A theology of world religions: Interpreting God, self, and world in Semitic, Indian, and Chinese thought . Augsburg Publishing House. ISBN 0-8066-2253-9.

- Maspero, Henri (1981). Taoism and Chinese Religion . Translated by Kierman, Frank A. Jr. University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 0-87023-308-4.

- Meyer, Milton Walter (1994). China: A Concise History (2nd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Littlefield Adams Quality Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-8476-7953-9.

- Moeller, Hans-Georg (2006). The Philosophy of the Daodejing . Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-13679-X.

- Ni, Xueting C. (2023). Chinese Myths: From Cosmology and Folklore to Gods and Immortals. London: Amber Books. ISBN 978-1-83886-263-3.

- Pulleyblank, E.G. (1991). Lexicon of Reconstructed Pronunciation in Early Middle Chinese, Late Middle Chinese, and Early Mandarin. UBC Press.

- Schuessler, Axel (2007). ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2975-9.

- Sharot, Stephen (2001). A Comparative Sociology of World Religions: virtuosos, priests, and popular religion. New York: NYU Press. ISBN 0-8147-9805-5.

- Stark, Rodney (2007). Discovering God: The Origins of the Great Religions and the Evolution of Belief (1st ed.). New York: HarperOne. ISBN 978-0-06-117389-9.

- Sterckx, Roel (2019). Chinese Thought. From Confucius to Cook Ding. London: Penguin.

- Taylor, Rodney Leon; Choy, Howard Yuen Fung (2005). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Confucianism, Volume 2: N-Z. Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8239-4081-0.

- Waley, Arthur (1958). The way and its power: a study of the Tao tê ching and its place in Chinese thought. Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-5085-3.

- Watts, Alan Wilson (1977). Tao: The Watercourse Way with Al Chung-liang Huang. Pantheon. ISBN 0-394-73311-8.

- Wright, Edmund, ed. (2006). The Desk Encyclopedia of World History. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-7394-7809-7.

- Zai, J. (2015). Taoism and Science: Cosmology, Evolution, Morality, Health and more. Ultravisum. ISBN 978-0-9808425-5-5.

- Zheng, Yangwen, ed. (2017). Sinicizing Christianity. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-33038-2.

- Zhou Fagao (周法高) (1972). "Shanggu Hanyu he Han-Zangyu" 上古漢語和漢藏語. Journal of the Institute of Chinese Studies of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (in Chinese). 5: 159–244.

Further reading

- Translation of the Tao te Ching by Derek Lin

- Translation of the Dao de Jing by James Legge

- Legge translation of the Tao Teh King at Project Gutenberg

- Feng, Gia-Fu & Jane English (translators). 1972. Laozi/Dao De Jing. New York: Vintage Books.

- Komjathy, Louis. Handbooks for Daoist Practice. 10 vols. Hong Kong: Yuen Yuen Institute, 2008.

- Mitchell, Stephen (translator). 1988. Tao Te Ching: A New English Version. New York: Harper & Row.

- Robinet, Isabelle; Brooks, Phyllis; Robinet, Isabelle (1997). Taoism: growth of a religion. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2839-3.

- Sterckx, Roel. Chinese Thought. From Confucius to Cook Ding. London: Penguin, 2019.

- Dao entry from Center for Daoist Studies

- The Tao of Physics , Fritjof Capra, 1975

External links

| Tao | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 道 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | way | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||