Basque is a language spoken by Basques and other residents of the Basque Country, a region that straddles the westernmost Pyrenees in adjacent parts of northern Spain and southwestern France. Basque is classified as a language isolate and the only language isolate in Europe. The Basques are indigenous to and primarily inhabit the Basque Country. The Basque language is spoken by 806,000 Basques in all territories. Of these, 93.7% (756,000) are in the Spanish area of the Basque Country and the remaining 6.3% (50,000) are in the French portion.

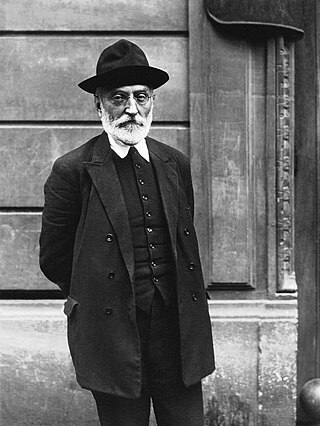

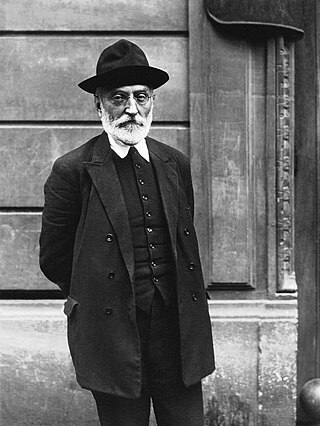

Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo was a Spanish essayist, novelist, poet, playwright, philosopher, professor of Greek and Classics, and later rector at the University of Salamanca.

Federico Krutwig Sagredo was a Spanish Basque writer, philosopher, politician, and author of several books, with Vasconia standing out in the political domain for its influence in the early stages of ETA, and as an advocate of classic Labourdin for the standardization of Basque. He distanced himself from Sabino Arana's brand of Basque nationalism, emphasizing language instead of race as pivotal for the Basque nation.

Augustin Chaho in French or Agosti Xaho in Basque was an important Romantic Basque writer. He was born in Tardets, Soule, French Basqueland on 10 October 1811 and died in Bayonne, Labourd 23 October 1858. He is considered a precursor of left-wing Basque patriotism.

Gabriel Aresti Segurola was one of the most important writers and poets in the Basque language in the 20th century.

Koldo Mitxelena Elissalt was an eminent Spanish Basque linguist. He taught in the Department of Philology at the University of the Basque Country, and was a member of the Royal Academy of the Basque Language.

Although the first instances of coherent Basque phrases and sentences go as far back as the San Millán glosses of around 950, the large-scale damage done by periods of great instability and warfare, such as the clan wars of the Middle Ages, the Carlist Wars and the Spanish Civil War, led to the scarcity of written material predating the 16th century.

Salbatore Mitxelena was a friar and a writer in the Basque language.

Nikolas Ormaetxea, also known as Orixe was a Basque language writer.

José Luis Álvarez Enparantza, better known by his pseudonym Txillardegi, was a Basque linguist, politician, and writer. He was born and raised in the Basque Country, and although he did not learn the Basque language until the age of 17, he later came to be considered one of the most influential figures in Basque nationalism and culture in the second half of the 20th century. He was one of the founders of ETA, but in 1967 he left because he did not agree with its political line.

Koldo Zuazo is a Basque linguist, professor at the University of the Basque Country and specialist in Basque language dialectology and sociolinguistics.

Jon Mirande was a Basque writer, poet and translator who lived in Paris. Mirande exerted a great literary influence in the 1970s and 1980s, writing in Basque literary and cultural magazines as well as Breton ones. He wrote poetry and short stories in his youth, and essays and novels in his later years. Mirande was a nationalist and believed in the value of ethnicity, especially in the Basque language, but he was also pagan and laid claim to the values of paganism and of the ancient Basques.

Laura Mintegi Lakarra is a Basque author, politician and a professor at the University of the Basque Country. Although she was born in Navarre, she moved to Biscay at an early age and has lived there ever since; first in Bilbao and later in Algorta.

Jakin is a Spanish cultural group, magazine, and publishing house. Founded in 1956, it is one of the oldest in Basque language. "Jakin" means "knowledge" in Basque and the magazine specializes on social and cultural issues. One of the leading members of Jakin is the philosopher Joxe Azurmendi. Currently, the editor-in-chief of Jakin is Lorea Agirre.

Iñaki Goirizelaia, PhD is a full professor of Telecommunication Engineering at the University of the Basque Country in the Department of Communication Engineering. In 1981 he began his work as a professor at the Faculty of Engineering of Bilbao. He is the former President of the University of the Basque Country (2009–2017). Previously, he was Vice-president of the Campus of Biscay of the same university (2005–2008).

Joxe Austin Arrieta Ugartetxea is a Basque writer and translator.

Mikel Zalbide Elustondo is a Basque linguist and sociolinguist.

Joan Mari Torrealdai Nabea was a Basque writer, journalist and sociologist. He was a member of Euskaltzaindia. He was born in Forua, Biscay, Basque Autonomous Community, Spain.

The Basque Summer University is a university institution created in 1973, which works to promote extensive use of Basque language at the university level. It promotes courses, book publications, Internet services, congresses, professional meetings and postgraduate degrees at university level and in Basque. It offers university courses in collaboration with the University of the Basque Country, Mondragon University, Public University of Navarra, the University of Pau and Pays de l'Adour in Bayonne, and Basque Wikipedia.

Joseba Agirreazkuenaga is a researcher and historian. He is specialist in the history of the Basque Country particularly: the crisis of the Ancien Régime; the fueros, self-governance, the economic concert between Spain and the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country and its fiscal system, and the social movements both in Bilbao and in the Basque Country as a whole.