History

Early Works

Scholars like Hobbes, who presented the idea of the social contract, created an emphasis on liberalism promoting individualism, equality, and consent. However, his ideas exclude women, making them hypocritical. Brennan and Pateman state, “Hobbes in particular, denied the central tenets of patriarchal theory. Moreover, to emphasize patriarchal arguments does nothing to explain why it is that social contract theory and patriarchal theory emerged together and engaged in mutual criticism.” [5]

The earliest works of feminist political theory come from texts written by white women defending women's abilities and moral capacity along with protesting about women's exclusion and subordination. Since then, feminist theory has been expanded to include the intersection of racism and sexism. Scholars like Kimberlé Crenshaw note that "the intersectional experience is greater than the sum of racism and sexism" [6] and that the early framework of feminist political theory ignored how Black women are marginalized. It wasn't until late in the 20th century that black women became included in feminism political theory. [7]

The origins of feminist political theory include texts written by women about women's abilities and their protesting about women's exclusion and subordination. Some key primary texts include:

Renaissance

In The Book of the City of Ladies (1450), Christine de Pizan praises women and defends their capabilities and virtues. She argues against contemporary writing that did not include women in political life. Pizan focuses on woman warriors, illuminating the contribution of women in political society. The work was considered rebellious at Pizan's time. [8]

Early Modern

Mary Astell's A Serious Proposal to the Ladies, for the Advancement of Their True and Greatest Interest" (1694) argues that women who do not intend to marry should use their dowries to finance residential women's colleges to provide the recommended education for upper- and middle-class women. Astell was one of the earliest critics of John Locke's political philosophy. She argued that Locke’ did not apply his theory of consent to government or his guarantees of "life, liberty, and property" to women. Patricia Springborg notes, " Her challenge to Locke to extend to women against domestic tyrants the liberty he claimed for subjects against the Crown was a subversive strataem" intended to expose “the tenets of contractarian liberalism” as hypocritical when restricted to men. [9]

Catharine Macaulay's Letters on Education (1790) intervened in Enlightenment debate about liberty, education and the social contract. In her work, "she fought for equality of women and criticized contemporary theories of gender difference." [10] Macaulay argues that women inferiority stemmed from mis-education instead of nature, directly challenging Rousseau's claim that women's subordination derived from inherent sexual differences. [11]

Olympia de Gouges's Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen (1971) was written as a direct response to the French Revolution's Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which was "the death knell for any hopes of inclusion of women's rights under the “Rights of Man.” [12] In her work, she argues "for women's active citizenship by criticizing the exclusion of women from the public sphere.” [13] Gouge talks about how women should enjoy the same civil and political rights as men and exposed the hypocrisy of revolutionary ideas that excluded women from citizenship and political participation.

Mary Wollstonecraft's A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), that argued that women's apparent inferiority to men was due to lack of educational resources, not nature. Her work is often considered the first major feminist text in the Western tradition, but her ideas draw upon many other early feminist thinkers, "she explicitly recognized the contribution of Hester Chapone and much admired--and borrowed from--Catherine Macaulay." [14]

Nineteenth Century

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Declaration of Sentiments (1848), was a document that modeled itself on the U.S. Declaration of Independence, asserting that women and men were created equal. Her work was written for the Seneca Falls Convention and was foundational to first-wave feminism. [15]

Twentieth Century

Virginia Woolf, A Room of One's Own (1929), argued that every woman needs a "room of her own", a luxury that men are able to enjoy without question, in order have the time and the space to engage in uninterrupted writing time. Molly Hite stated, "A Room of One's Own was a foundational document in the late twentieth-century rediscovery of a female literary tradition. It led generations of feminist scholars to repopulate the field of modernist literary studies with innovative, influential, and successful women writers of prose and poetry." [16]

Simone de Beauvoir's, The Second Sex (1949), examined how women are socially constructed as "the Other" through cultural systems. She exposed the power dynamics surrounding womanhood, Judith Butler explained that Beauvoir's insight “distinguishes sex from gender and suggests that gender is an aspect of identity gradually acquired." [17]

Several accounts of feminist political theory emphasize the abstract principles of equality, but KT Bartlett's, Feminist Legal Methods (1990) argues that feminist analysis must also examine how legal rules are shaped by the experiences and values of those in power. [18] Her work shows that feminist legal methods show hidden biases within supposedly neutral laws by focusing on lived experience and the unequal effects of legal decisions on different groups. [18]

Contemporary Movementsand Understandings

Feminist political philosophy expanded from “the struggles of the feminist movements of the twentieth century” in order to refine the ideas of feminism, to political issues instead of personal. Ericka Tucker sees feminist political theory as redefining what counts as political by exposing how power operates and redefining political norms. She notes that feminism is not restrictive to women and gender, but rather encompasses understanding how power works for and against people in society. This field of philosophical questioning combines the traditional structures, assumptions and exclusions that are prominent in mainstream political thought. Feminist political theory aims to reshape and reconstruct the political sphere to be equal for all. Feminist political theory combines aspects of both feminist theory and political theory in order to take a feminist approach to traditional questions within political philosophy. [2]

More recent movements include the MeToo movement which demonstrated how feminist political theory continues to influence activism. This specific movement represented how harassment aren't isolated incidents but rather the consequence of the current political structures that allow these injustices to occur.

Feminist political theory is not just about women or gender. There are no strict necessary and sufficient conditions for being ‘feminist’, due both to the nature of categories and to the myriad developments, orientations and approaches within feminism. [19] Although understanding and analyzing the political effects of gendered contexts is an important field of feminist political theory, feminist theory, and hence feminist political theory, is about more than gender. Feminist political theorists are found throughout the academy, in departments of political science, history, women's studies, sociology, geography, anthropology, religion, and philosophy. [19] Recent feminist political theory has also been reshaped by trans activism and the development of transfeminism, which argues that feminism must include how gender norms and patriarchal violence affect transgender and gender-nonconforming people. [20]

Feminist political theory encompasses a broad scope of approaches. It overlaps with related areas including feminist jurisprudence/feminist legal theory; feminist political philosophy; ecological feminism; female-centered empirical research in political science; and feminist research methods (feminist method) for use in political science the social sciences.

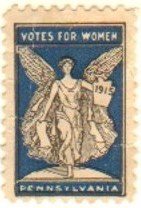

Women's Rights Movement (1800s - early 1900s)

Women's involvement in the women's right movement began mostly as a part of the international movement to abolish slavery. The Women's Rights Movement in the U.S. “mirrored similar struggles throughout Europe, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.” [21] During this, the women participating sought equal political rights with men, namely the right to vote. They also countered the societal norms of women as being weak, irrational and unable to participate in politics by arguing against the cult of domesticity that women were entitled to the same civil and political rights. Furthermore, the members of the suffrage movement worked for women's rights to divorce, rights to inheritance, rights to matriculate into colleges and universities, and more. [2]

Many early women activists discovered their political voices through antislavery movements. Women such as Angelina and Sarah Grimké, "saw in the bonds of womanhood their deep connection with Black women" stating "They are our countrywomen, they are our sisters; and to us, as women, they have a right to look for sympathy for their sorrow, and effort and prayer for their rescue." [22] Sojourner Truth is another example of someone who insisted on recognition of Black women's rights within women's conventions. However, Black women weren't always included as "Few activist women of the period shared the Grimkés’ and Truth's sensitivity to the position of Black women." [22] Other white suffragists focused primarily on the legal concerns of middle-class white women, leaving Black women out of the feminist movement. [22]

Women's Liberation Movement (1960s -1970s)

Feminist political theory as a term only consolidated in the West during Women's liberation movement of the 1960s and 70s.

The women's liberation movement was a collective struggle for equality during the late 1960s and 1970s. This movement, which consisted of women's liberation groups, advocacy, protests, consciousness-raising, and feminist theory, sought to free women from oppression and male supremacy. [23]

Several distinct stages of feminism that arose from this movement are explained below. [24]

Radical feminism

Radical feminism argues that at the heart of women's oppression is pervasive male domination, which is built into the conceptual and social architecture of modern patriarchal societies. Men dominate women not just through violence and exclusion but also through language. [2] Thus came to be Catharine A. MacKinnon's famous line, “Man fucks woman; subject verb object.” [25] Radical feminists argue that, because of patriarchy, women have come to be viewed as the "other" to the male norm, and as such have been systematically oppressed and marginalized. [26]

Early radical feminism was grounded in the rejection of the nuclear family and femininity as constructed within heterosexuality. [27] The strongest forms of radical feminism argue that there can be no reform, but only recreation of the notions of family, partnership, and childrearing, and that to do so in a way that preserves women's dignity requires the creation of women-only spaces. [2]

Liberal feminism

Liberal feminism argues that the central aims of liberal theory: freedom, equality, universal human rights and justice are also the proper aims of feminist theory. Its primary focus is to achieve gender equality through political and legal reform within the framework of liberal democracy. [28]

Liberal feminists use figures and concepts from the liberal tradition to develop feminist institutions and political analyses. They suggest that emancipating women requires that women be treated and recognized as equal, rights bearing human agents. [2] A common theme of liberal feminism is an emphasis on equal opportunity via fair opportunity and equal political rights. [3]

Marxist and socialist feminism

Marxist feminism is a philosophical variant of feminism that incorporates and extends Marxist theory. It recognizes that women are oppressed and attributes the oppression to capitalism and the individual ownership of private property. [29] Thus they insist that the only way to end the oppression of women and achieve the women's liberation is to overthrow the capitalist system in which they contend much of women's labor is uncompensated. [30]

Socialist feminism is the result of Marxism meeting radical feminism. Socialist feminists consider how sexism and the gendered division of labor of each historical era is determined by the economic system of the time, largely expressed through capitalist and patriarchal relations. They believe that women's liberation must be sought in conjunction with the social and economic justice of all people and see the fight to end male supremacy as key to social justice. [31]

Ecological feminism

Ecological feminism is the branch of feminism that examines the connections between women and nature. Connections between environment and gender can be made by looking at the gender division of labor and environmental roles rather than an inherent connection with nature. The gender division of labor requires a more nurturing and caring role for women, therefore that caring nature places women closer with the environment. [32]

In the 1970s, the impacts of post-World War II technological development led many women to organize against issues from the toxic pollution of neighborhoods to nuclear weapons testing on indigenous lands. This grassroots activism emerging across every continent was both intersectional and cross-cultural in its struggle to protect the conditions for reproduction of Life on Earth. [33]

Postmodernist/Poststructuralist feminism

Postmodernist feminism rejects the dualisms of the previous 20 years of feminist theory: man/woman, reason/emotion, difference/equality. It challenges the very notion of stable categories of sex, gender, race or sexuality. [2] Postmodernist feminists agree with others that gender is the most important identity, however what makes Postmodern feminists different is that they are interested in how people 'pick and mix' their identities. They are also interested in the topic of masculinity, and instead reject the stereotypical aspects of feminism, embracing it as a positive aspect of identity. One of their key goals is to disable the patriarchal norms that have led to gender inequality. [34]