The German revolutions of 1848–1849, the opening phase of which was also called the March Revolution, were initially part of the Revolutions of 1848 that broke out in many European countries. They were a series of loosely coordinated protests and rebellions in the states of the German Confederation, including the Austrian Empire. The revolutions, which stressed pan-Germanism, demonstrated popular discontent with the traditional, largely autocratic political structure of the thirty-nine independent states of the Confederation that inherited the German territory of the former Holy Roman Empire after its dismantlement as a result of the Napoleonic Wars. This process began in the mid-1840s.

Friedrich Wilhelm Rüstow was a Prussian-born Swiss soldier and military writer.

Georg Friedrich Rudolph Theodor Herwegh was a German poet, who is considered part of the Young Germany movement.

Gustav Struve, known as Gustav von Struve until he gave up his title, was a German surgeon, politician, lawyer and publicist, and a revolutionary during the German revolutions of 1848–1849 in Baden, Germany. He also spent over a decade in the United States and was active there as a reformer.

Friedrich Franz Karl Hecker was a German lawyer, politician and revolutionary. He was one of the most popular speakers and agitators of the 1848 Revolution. After moving to the United States, he served as a brigade commander in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Pasewalk is a town in the Vorpommern-Greifswald district, in the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern in Germany. Located on the Uecker river, it is the capital of the former Uecker-Randow district, and the seat of the Uecker-Randow-Tal Amt, of which it is not part.

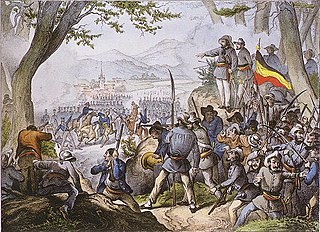

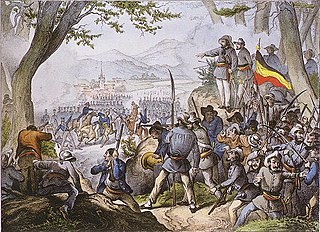

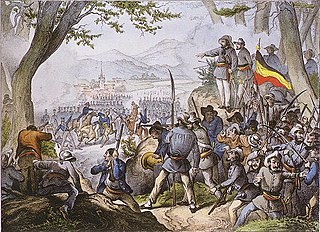

The Hecker uprising was an attempt in April 1848 by Baden revolutionary leaders Friedrich Hecker, Gustav von Struve, and several other radical democrats to overthrow the monarchy and establish a republic in the Grand Duchy of Baden. The uprising was the first major clash in the Baden Revolution and among the first in the March Revolution in Germany, part of the broader Revolutions of 1848 across Europe. The main action of the uprising consisted of an armed civilian militia under the leadership of Friedrich Hecker moving from Konstanz on the Swiss border in the direction of Karlsruhe, the ducal capital, with the intention of joining with another armed group under the leadership of revolutionary poet Georg Herwegh there to topple the government. The two groups were halted independently by the troops of the German Confederation before they could combine forces.

Henry Boernstein [in Europe, Heinrich Börnstein] was a German revolutionary who served as the publisher of the Anzeiger des Westens in St. Louis, Missouri, the oldest German newspaper west of the Mississippi River. He was also a political activist, author, soldier, actor and stage manager, and was briefly yet closely acquainted with Karl Marx during his tenure as publisher of the radical newspaper Vorwärts. He played a major role in keeping Missouri in the Union at the start of the Civil War.

Friedrich Wilhelm Schulz was a German officer, political writer and radical liberal publisher in Hesse. His most famous works are Der Tod des Pfarrers Friedrich Ludwig Weidig as well as Die Bewegung der Produktion, which Karl Marx quoted extensively in his 1844 Manuscripts. Schulz was the first to describe the movement of society "as flowing from the contradiction between the forces of production and the mode of production," which would later form the basis of historical materialism. Marx continued to praise Schulz's work decades later when writing Das Kapital.

The Baden Revolution of 1848/1849 was a regional uprising in the Grand Duchy of Baden which was part of the revolutionary unrest that gripped almost all of Central Europe at that time.

The factions in the Frankfurt Assembly were groups that developed among delegates to the Frankfurt Parliament that met from 18 May 1848 to 31 May 1849 in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt am Main. They coalesced as groups of like-minded representatives started meeting, and were named after the various hostelries at which they met.

The Palatine uprising was a rebellion that took place in May and June 1849 in the Rhenish Palatinate, then an exclave territory of the Kingdom of Bavaria. Related to uprisings across the Rhine river in Baden, it was part of the widespread Imperial Constitution Campaign (Reichsverfassungskampagne). Revolutionaries worked to defend the constitution as well as to secede from the Kingdom of Bavaria.

The Freischar was the German name given to an irregular, volunteer military unit that, unlike regular or reserve military forces, participated in a war without the formal authorisation of one of the belligerents, but on the instigation of a political party or an individual. A Freischar deployed against a foreign enemy was often called a Freikorps. The term Freischar has been commonly used in German-speaking Europe since 1848. The members of a Freischar were called Freischärler. As early as 1785 Johann von Ewald published in Kassel his Essay on Partisan Warfare, which described his experiences with the rebels in the North American colonies.

The Battle on the Scheideck, also known as the Battle of Kandern took place on 20 April 1848 during the Baden Revolution on the Scheideck Pass southeast of Kandern in south Baden in what is now southwest Germany. Friedrich Hecker's Baden band of revolutionaries encountered troops of the German Confederation under the command of General Friedrich von Gagern. After several negotiations and some skirmishing a short battle ensued on the Scheideck, in which von Gagern fell and the rebels were scattered. The German Federal Army took up the pursuit and dispersed a second revolutionary force that same day under the leadership of Joseph Weißhaar. The Battle on the Scheideck was the end of the road for the two rebel forces. After the battle, there were disputes over the circumstances of von Gagern's death.

Karl Georg Heinrich Bernhard von Poten, known as Bernhard von Poten, was a royal Prussian colonel best known for his military writing.

Emma Herwegh was a German salonnière and woman of letters who participated in the 1848 uprisings, undertaking at least one secret quasi-diplomatic mission on behalf of the Legion of German Democrats. She is known to posterity in particular, partly because she married the poet and activist Georg Herwegh, and partly because she was an exceptionally prolific letter writer.

The Wiesental, named after the river Wiese, is a valley in the Southern Black Forest. The Wiese is a right-hand tributary of the Rhine which has its source in Feldberg and flows into the Rhine in Basel, Switzerland. The Wiesental was one of the first industrialized regions of the former grand dutchy of Baden and an important production location for the textile industry.

Amalie Struve was a democratic radical participant in the 1848 March Revolution. She is also remembered as an early feminist and author.

The Battle of Günterstal took place on 23 April 1848 during the Baden Revolution at Jägerbrunnen not far from the village of Günterstal. Here government troops stopped a vanguard of the militants who were advancing towards the city of Freiburg im Breisgau under Franz Sigel.

The Baden Army was the military organisation of the German state of Baden until 1871. The origins of the army were a combination of units that the Badenese margraviates of Baden-Durlach and Baden-Baden had set up in the Baroque era, and the standing army of the Swabian Circle, to which both territories had to contribute troops. The reunification of the two small states to form the Margraviate of Baden in 1771 and its subsequent enlargement and elevation by Napoleon to become the Grand Duchy of Baden in 1806 created both the opportunity and obligation to maintain a larger army, which Napoleon used in his campaigns against Austria, Prussia and Spain and, above all, Russia. After the end of Napoleon's rule, the Grand Duchy of Baden contributed a division to the German Federal Army. In 1848, Badenese troops helped to suppress the Hecker uprising, but a year later a large number sided with the Baden revolutionaries. After the violent suppression of the revolution by Prussian and Württemberg troops, the army was re-established and fought in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 on the side of Austria and the southern German states, as well as in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 on the side of the Germans. When Baden joined the German Empire in 1870/71, the Grand Duchy gave up its military sovereignty and the Badenese troops became part of the XIV Army Corps of the Imperial German Army.