Justus was the fourth archbishop of Canterbury. Pope Gregory the Great sent Justus from Italy to England on a mission to Christianise the Anglo-Saxons from their native paganism; he probably arrived with the second group of missionaries despatched in 601. Justus became the first bishop of Rochester in 604 and signed a letter to the Irish bishops urging the native Celtic church to adopt the Roman method of calculating the date of Easter. He attended a church council in Paris in 614.

Malmesbury Abbey, at Malmesbury in Wiltshire, England, is a former Benedictine abbey dedicated to Saint Peter and Saint Paul. It was one of the few English religious houses with a continuous history from the 7th century through to the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

Æthelweard was an ealdorman and the author of a Latin version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle known as the Chronicon Æthelweardi. He was a kinsman of the royal family, being a descendant of the Anglo-Saxon King Æthelred I of Wessex, the elder brother of Alfred the Great.

William of Malmesbury was the foremost English historian of the 12th century. He has been ranked among the most talented English historians since Bede. Modern historian C. Warren Hollister described him as "a gifted historical scholar and an omnivorous reader, impressively well versed in the literature of classical, patristic, and earlier medieval times as well as in the writings of his own contemporaries. Indeed William may well have been the most learned man in twelfth-century Western Europe."

Ælfweard was the second son of Edward the Elder, the eldest born to his second wife Ælfflæd.

Osmund, Count of Sées, was a Norman noble and clergyman. Following the Norman conquest of England, he served as Lord Chancellor and as the second bishop of Salisbury, or Old Sarum.

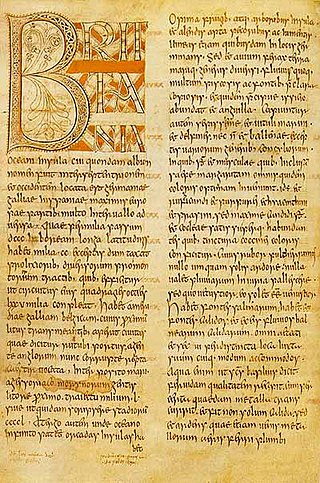

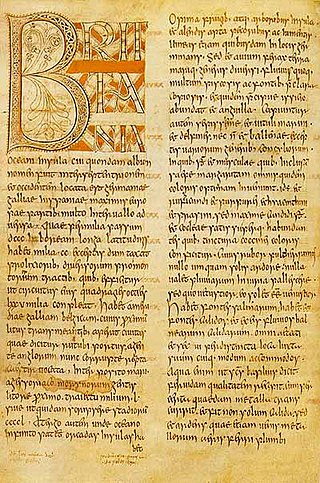

The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, written by Bede in about AD 731, is a history of the Christian Churches in England, and of England generally; its main focus is on the conflict between the pre-Schism Roman Rite and Celtic Christianity. It was composed in Latin, and is believed to have been completed in 731 when Bede was approximately 59 years old. It is considered one of the most important original references on Anglo-Saxon history, and has played a key role in the development of an English national identity.

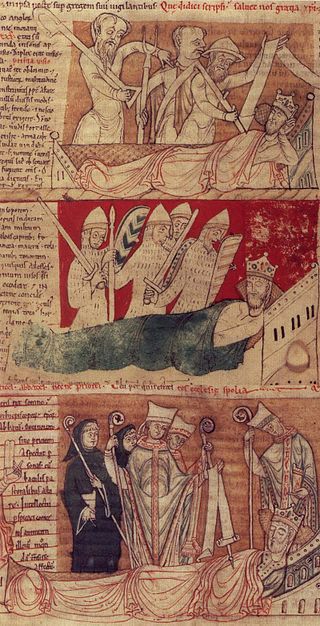

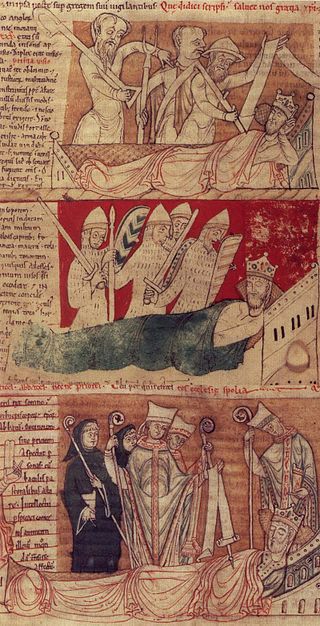

Historians in England during the Middle Ages helped to lay the groundwork for modern historical historiography, providing vital accounts of the early history of England, Wales and Normandy, its cultures, and revelations about the historians themselves.

Stigand was the last Bishop of Selsey, and first Bishop of Chichester.

Francis Thynne was an English antiquary and an officer of arms at the College of Arms.

Æthelwold, also known as Æthelwald or Æþelwald, was a 7th-century king of East Anglia, the long-lived Anglo-Saxon kingdom which today includes the English counties of Norfolk and Suffolk. He was a member of the Wuffingas dynasty, which ruled East Anglia from their regio at Rendlesham. The two Anglo-Saxon cemeteries at Sutton Hoo, the monastery at Iken, the East Anglian see at Dommoc and the emerging port of Ipswich were all in the vicinity of Rendlesham.

John of Worcester was an English monk and chronicler who worked at Worcester Priory. He is now usually held to be the author of the Chronicon ex Chronicis.

The Gesta Regum Anglorum, originally titled De Gestis Regum Anglorum and also anglicized as The Chronicles or The History of the Kings of England, is an early-12th-century history of the kings of England by William of Malmesbury. It is a companion work of his Gesta Pontificum Anglorum and was followed by his Historia Novella, which continued its account for several more years. The portions of the work concerning the First Crusade were derived from Gesta Francorum Iherusalem peregrinantium, a chronicle by Fulcher of Chartres.

Pehthelm was the first historical bishop of the episcopal see of Candida Casa at Whithorn. He was consecrated in 730 or 731 and served until his demise. His name is also spelled as Pecthelm, Pechthelm, and sometimes as Wehthelm.

Ælfgifu of Shaftesbury was the first wife of King Edmund I. She was Queen of the English from her marriage in around 939 until her death in 944. Ælfgifu and Edmund were the parents of two future English kings, Eadwig and Edgar. Like her mother Wynflaed, Ælfgifu had a close and special if unknown connection with the royal nunnery of Shaftesbury (Dorset), founded by King Alfred, where she was buried and soon revered as a saint. According to a pre-Conquest tradition from Winchester, her feast day is 18 May.

The Liber Eliensis is a 12th-century English chronicle and history, written in Latin. Composed in three books, it was written at Ely Abbey on the island of Ely in the fenlands of eastern Cambridgeshire. Ely Abbey became the cathedral of a newly formed bishopric in 1109. Traditionally the author of the anonymous work has been given as Richard or Thomas, two monks at Ely, one of whom, Richard, has been identified with an official of the monastery, but some historians hold that neither Richard nor Thomas was the author.

Tidfrith or Tidferth was an early 9th-century Northumbrian prelate. Said to have died on his way to Rome, he is the last known Anglo-Saxon bishop of Hexham. This bishopric, like the bishopric of Whithorn, probably ceased to exist, and was probably taken over by the authority of the bishopric of Lindisfarne. A runic inscription on a standing cross found in the cemetery of the church of Monkwearmouth is thought to bear his name.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons.

Æthelwine of Athelney was a 7th-century saint venerated in the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches. He lived as a hermit on the island of Athelney in the marsh country of Somerset, and is known to us through being recorded in the hagiography of the Secgan Manuscript. He was venerated as a saint after his death, Nov. 26.

Eadwold of Cerne, also known as Eadwold of East Anglia, was a 9th-century hermit, East Anglian prince and patron saint of Cerne, Dorset, who lived as a hermit on a hill about four miles from Cerne. His feast day is 29 August.