Marginalia (or apostils) are marks made in the margins of a book or other document. They may be scribbles, comments, glosses (annotations), critiques, doodles, drolleries, or illuminations.

Marginalia (or apostils) are marks made in the margins of a book or other document. They may be scribbles, comments, glosses (annotations), critiques, doodles, drolleries, or illuminations.

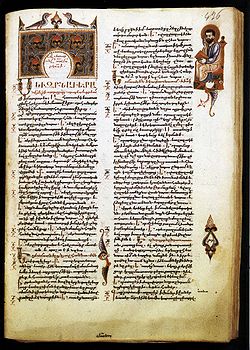

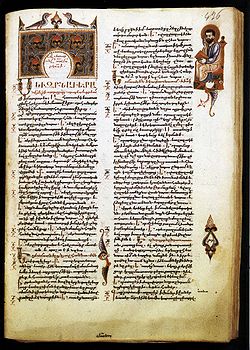

Biblical manuscripts have notes in the margin, for liturgical use. Numbers of texts' divisions are given at the margin (κεφάλαια, Ammonian Sections, Eusebian Canons). There are some scholia, corrections and other notes usually made later by hand in the margin. Marginalia may also be of relevance because many ancient or medieval writers of marginalia may have had access to other relevant texts that, although they may have been widely copied at the time, have since then been lost due to wars, prosecution, or censorship. As such, they might give clues to an earlier, more widely known context of the extant form of the underlying text than is currently appreciated. For this reason, scholars of ancient texts usually try to find as many surviving manuscripts of the texts they are researching as possible, because the notes scribbled in the margins might contain additional clues to the interpretation of these texts.

One of the earliest forms of marginal commentary were scholia, or written notes in the margins of text, typically provided by the scribe who created the handwritten manuscript copy. [1] Three ancient Greek Homeric scholars — Zenodotus of Ephesus, Aristophanes of Byzantium, and Aristarchus of Samothrace —who were all librarians at the Library of Alexandria, successively developed a system of symbols to be used in the margins of Homer's poetry. Named after the obelus, which evolved into the modern dagger †, this system of marking up a text with a set of symbols for scholarly commentary became known as obelism. [2] Among these Aristarchian symbols, the ancora, an anchor-shaped pointer ⸔ or ⸕, was used to draw attention to a passage. [3]

In Europe, before the invention of the printing press, books were copied by hand, originally onto vellum and later onto paper. Paper was expensive and vellum was much more expensive. A single book cost as much as a house. Books, therefore, were long-term investments expected to be handed down to succeeding generations. Readers commonly wrote notes in the margins of books in order to enhance the understanding of later readers. Of the 52 extant manuscript copies of Lucretius' "De rerum natura" (On the Nature of Things) available to scholars, all but three contain marginal notes. [4]

The practice of writing in the margins of books gradually declined over several centuries after the invention of the printing press. Printed books gradually became much less expensive, so they were no longer regarded as long-term assets to be improved for succeeding generations. The first Gutenberg Bible was printed in the 1450s. Hand annotations occur in most surviving books through the end of the 1500s. [4] Marginalia did not become unusual until sometime in the 1800s.

Fermat's claim, written around 1637, of a proof of Fermat's last theorem too big to fit in the margin is the most famous mathematical marginal note. [5] Voltaire, in the 1700s, annotated books in his library so extensively that his annotations have been collected and published. [6] The first recorded use of the word marginalia is in 1819 in Blackwood's Magazine . [7] From 1845 to 1849 Edgar Allan Poe titled some of his reflections and fragmentary material "Marginalia". [8] [9] Five volumes of Samuel T. Coleridge's marginalia have been published. Beginning in the 1990s, attempts have been made to design and market e-book devices permitting a limited form of marginalia.

Some famous marginalia were serious works, or drafts thereof, written in margins due to scarcity of paper. Voltaire composed in book margins while in prison, and Sir Walter Raleigh wrote a personal statement in margins just before his execution.

Marginalia can add to or detract from the value of an association copy of a book, depending on the author of the marginalia and on the book.

Catherine C. Marshall, doing research on the future of user interface design, has studied the phenomenon of user annotation of texts. She discovered that in several university departments, students would scour the piles of textbooks at used book dealers for consistently annotated copies. The students had a good appreciation for their predecessors' distillation of knowledge. [10] [11] [12] In recent years, the marginalia left behind by university students as they engage with library textbooks has also been a topic of interest to sociologists looking to understand the experience of being a university student. [13] [14]

The former Moscow correspondent of The Financial Times, John Lloyd, has stated that he was shown Stalin's copy of Machiavelli's The Prince , with marginal comments. [15]

American poet Billy Collins has explored the phenomenon of annotation within his poem titled "Marginalia". [16]

In the last thirty years or so, many efforts have been made to analyze and understand marginalia found within Illuminated manuscripts. However, multiple theories exist as to its function and meaning within context. One study on medieval and Renaissance manuscripts where snails are depicted on marginalia shows that these illustrations are a comic relief due to the similarity between the armor of knights and the shell of snails. [17] [18] [19] Other studies of marginalia indicate it was used to provide additional commentary and support for surrounding text. Some types of marginalia may have also been a scribe’s form of artistic expression and skill while others were deliberate exaggerations to humor and entertain the reader. In addition, other marginalia may have existed as moral guides, providing bad examples of what behaviors should not be imitated. Lastly, some manuscript scholars believe medieval illuminators utilized marginalia due to fear of empty space left on pages or simply to supply a form of ornate meaningless distraction for the reader. [20] [21] Other examples of marginalia found within medieval manuscripts include drawings of centaurs, warrior women, battles between cats and mice, parables from biblical texts, personified foxes, rabbits, and monkeys, and hidden words and messages buried within border decorations. [22]