Eärendil the Mariner and his wife Elwing are characters in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth legendarium. They are depicted in The Silmarillion as Half-elven, the children of Men and Elves. He is a great seafarer who, on his brow, carried the Morning Star, a jewel called a Silmaril, across the sky. The jewel had been saved by Elwing from the destruction of the Havens of Sirion. The Morning Star and the Silmarils are elements of the symbolism of light, for divine creativity, continually splintered as history progresses. Tolkien took Eärendil's name from the Old English name Earendel, found in the poem Crist I, which hailed him as "brightest of angels"; this was the beginning of Tolkien's Middle-earth mythology. Elwing is the granddaughter of Lúthien and Beren, and is descended from Melian the Maia, while Earendil is the son of Tuor and Idril. Through their progeny, Eärendil and Elwing became the ancestors of the Númenorean, and later Dúnedain, royal bloodline.

Glorfindel is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth legendarium. He is a member of the Noldor, one of the three groups of High Elves. The character and his name, which means "blond" or "golden-haired", were among the first created for what would become part of his Middle-earth legendarium in 1916–17, beginning with the initial draft of The Fall of Gondolin. His name indicates his hair as a mark of his distinction, as the Noldor were generally dark-haired. A character of the same name appears in the first book of The Lord of the Rings, The Fellowship of the Ring, which takes place in Middle-earth's Third Age. Within the story, he is depicted as a powerful Elf-lord who could withstand the Nazgûl, wraith-like servants of Sauron, and holds his own against some of them single-handedly. Glorfindel and a version of the story of the Fall of Gondolin appear in The Silmarillion, posthumously published in 1977.

A Balrog is a powerful demonic monster in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth. One first appeared in print in his high-fantasy novel The Lord of the Rings, where the Fellowship of the Ring encounter a Balrog known as Durin's Bane in the Mines of Moria. Balrogs appear also in Tolkien's The Silmarillion and his legendarium. Balrogs are tall and menacing beings who can shroud themselves in fire, darkness, and shadow. They are armed with fiery whips "of many thongs", and occasionally use long swords.

In the works of J. R. R. Tolkien, the Noldor are a kindred of Elves who migrate west to the blessed realm of Valinor from the continent of Middle-earth, splitting from other groups of Elves as they went. They then settle in the coastal region of Eldamar. The Dark Lord Morgoth murders their first leader, Finwë. The majority of the Noldor, led by Finwë's eldest son Fëanor, then return to Beleriand in the northwest of Middle-earth. This makes them the only group to return and then play a major role in Middle-earth's history; much of The Silmarillion is about their actions. They are the second clan of the Elves in both order and size, the other clans being the Vanyar and the Teleri.

Tuor Eladar and Idril Celebrindal are fictional characters from J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth legendarium. They are the parents of Eärendil the Mariner and grandparents of Elrond Half-elven: through their progeny, they become the ancestors of the Númenóreans and of the King of the Reunited Kingdom Aragorn Elessar. Both characters play a pivotal role in The Fall of Gondolin, one of Tolkien's earliest stories; it formed the basis for a section in his later work, The Silmarillion, and was expanded as a standalone publication in 2018.

In J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth, the Eagles or Great Eagles, are immense birds that are sapient and can speak. The Great Eagles resemble actual eagles, but are much larger. Thorondor is said to have been the greatest of all birds, with a wingspan of 30 fathoms. Elsewhere, the Eagles have varied in nature and size both within Tolkien's writings and in later adaptations.

Húrin is a fictional character in the Middle-earth legendarium of J. R. R. Tolkien. He is introduced in The Silmarillion as a hero of Men during the First Age, said to be the greatest warrior of both the Edain and all Men in Middle-earth. His actions, however, bring catastrophe and ruin to his family and to the people of Beleriand.

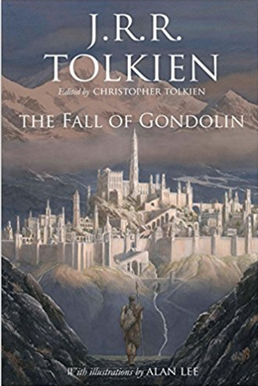

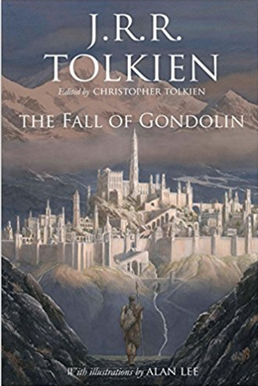

J. R. R. Tolkien's The Fall of Gondolin is a 2018 book of fantasy fiction by J. R. R. Tolkien, edited by his son Christopher. The story is one of what Tolkien called the three "Great Tales" from the First Age of Middle-earth; the other two are Beren and Lúthien and The Children of Húrin. All three stories are briefly summarised in the 1977 book The Silmarillion, and all three have now been published as stand-alone books. A version of the story also appears in The Book of Lost Tales. In the narrative, Gondolin was founded by King Turgon in the First Age. The city was carefully hidden, enduring for centuries before being betrayed and destroyed. Written in 1917, it is one of the first stories of Tolkien's legendarium.

The fictional races and peoples that appear in J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy world of Middle-earth include the seven listed in Appendix F of The Lord of the Rings: Elves, Men, Dwarves, Hobbits, Ents, Orcs and Trolls, as well as spirits such as the Valar and Maiar. Other beings of Middle-earth are of unclear nature such as Tom Bombadil and his wife Goldberry.

J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth legendarium features dragons based on those of European legend, but going beyond them in having personalities of their own, such as the wily Smaug, who has features of both Fafnir and the Beowulf dragon.

Morgoth Bauglir is a character, one of the godlike Valar, from Tolkien's legendarium. He is the primary antagonist of Tolkien's legendarium, the mythic epic published in parts as The Silmarillion, The Children of Húrin, Beren and Lúthien, and The Fall of Gondolin.

The Silmarillion is a book consisting of a collection of myths and stories in varying styles by the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien. It was edited, partly written, and published posthumously by his son Christopher Tolkien in 1977, assisted by Guy Gavriel Kay, who became a fantasy author. It tells of Eä, a fictional universe that includes the Blessed Realm of Valinor, the ill-fated region of Beleriand, the island of Númenor, and the continent of Middle-earth, where Tolkien's most popular works—The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings—are set. After the success of The Hobbit, Tolkien's publisher, Stanley Unwin, requested a sequel, and Tolkien offered a draft of the writings that would later become The Silmarillion. Unwin rejected this proposal, calling the draft obscure and "too Celtic", so Tolkien began working on a new story that eventually became The Lord of the Rings.

The naming of weapons in Middle-earth is the giving of names to swords and other powerful weapons in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium. He derived the naming of weapons from his knowledge of Medieval times; the practice is found in Norse mythology and in the Old English poem Beowulf. Among the many weapons named by Tolkien are Orcrist and Glamdring in The Hobbit, and Narsil / Andúril in The Lord of the Rings. Such weapons carry powerful symbolism, embodying the identity and ancestry of their owners.

J. R. R. Tolkien invented heraldic devices for many of the characters and nations of Middle-earth. His descriptions were in simple English rather than in specific blazon. The emblems correspond in nature to their bearers, and their diversity contributes to the richly-detailed realism of his writings.

Tolkien's monsters are the evil beings, such as Orcs, Trolls, and giant spiders, who oppose and sometimes fight the protagonists in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth legendarium. Tolkien was an expert on Old English, especially Beowulf, and several of his monsters share aspects of the Beowulf monsters; his Trolls have been likened to Grendel, the Orcs' name harks back to the poem's orcneas, and the dragon Smaug has multiple attributes of the Beowulf dragon. The European medieval tradition of monsters makes them either humanoid but distorted, or like wild beasts, but very large and malevolent; Tolkien follows both traditions, with monsters like Orcs of the first kind and Wargs of the second. Some scholars add Tolkien's immensely powerful Dark Lords Morgoth and Sauron to the list, as monstrous enemies in spirit as well as in body. Scholars have noted that the monsters' evil nature reflects Tolkien's Roman Catholicism, a religion which has a clear conception of good and evil.

J. R. R. Tolkien, a devout Roman Catholic, created what he came to feel was a moral dilemma for himself with his supposedly evil Middle-earth peoples like Orcs, when he made them able to speak. This identified them as sentient and sapient; indeed, he portrayed them talking about right and wrong. This meant, he believed, that they were open to morality, like Men. In Tolkien's Christian framework, that in turn meant they must have souls, so killing them would be wrong without very good reason. Orcs serve as the principal forces of the enemy in The Lord of the Rings, where they are slaughtered in large numbers in the battles of Helm's Deep and the Pelennor Fields in particular.

Tom Loback was an artist, known for his illustrations of characters from J. R. R. Tolkien's 1977 book The Silmarillion, his miniature figurines, and his public artworks in New York. He contributed also as a Tolkien scholar interested in Tolkien's constructed languages.

J. R. R. Tolkien derived the characters, stories, places, and languages of Middle-earth from many sources, especially medieval ones. Tolkien and the classical world have been linked by scholars, and by Tolkien himself. The suggested influences include the pervasive classical themes of divine intervention and decline and fall in Middle-earth; the splendour of the Atlantis-like lost island kingdom of Númenor; the Troy-like fall of Gondolin; the Rome-like stone city of Minas Tirith in Gondor; magical rings with parallels to the One Ring; and the echoes of the tale of Lúthien and Beren with the myth of Orpheus descending to the underworld. Other possible connections have been suggested by scholars.