Kamarupi Prakrit is the postulated Middle Indo-Aryan (MIA) Prakrit language used in ancient Kamarupa. This language has been derived from Gauda-Kamarupi Prakrit and the historical ancestor of the Kamatapuri lects and the modern Assamese language; and can be dated prior to 1250 CE, when the proto-Kamta language, the parent of the Kamatapuri lects, began to develop. Though not substantially proven, the existence of the language that predated the Kamatapuri lects and modern Assamese is widely believed to be descended from it.

The Assam Movement (1979–1985) was a popular uprising in Assam, India, that demanded the Government of India detect, disenfranchise and deport illegal aliens. Led by All Assam Students Union (AASU) and All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad (AAGSP) the movement defined a six-year period of sustained civil disobedience campaigns, political instability and widespread ethnic violence. The movement ended in 1985 with the Assam Accord.

Goalpariya is a group of Indo-Aryan dialects spoken in the Goalpara region of Assam, India. Along with Kamrupi, they form the western group of Assamese dialects. The North Bengali dialect is situated to its west, amidst a number of Tibeto-Burman speech communities. The basic characteristic of the Goalpariya is that it is a composite one into which words of different concerns and regions have been amalgamated. Deshi people speak this language and there are around 20 lakhs people.

The Brahmaputra Valley is a region situated between hill ranges of the eastern and northeastern Himalayan range in Eastern India.

The Nellie massacre took place in central Assam during a six-hour period on the morning of 18 February 1983. The massacre claimed the lives of 1,600–2,000 people from 14 villages—Alisingha, Khulapathar, Basundhari, Bugduba Beel, Bugduba Habi, Borjola, Butuni, Dongabori, Indurmari, Mati Parbat, Muladhari, Mati Parbat no. 8, Silbheta, Borburi and Nellie—of Nagaon district. The victims were Muslim of Bengali origin. Three media personnel—Hemendra Narayan of The Indian Express, Bedabrata Lahkar of The Assam Tribune and Sharma of ABC—were witnesses to the massacre.

The Noakhali riots were a series of semi-organized massacres, rapes and abductions, combined with looting and arson of Hindu properties, perpetrated by the Muslim mobs in the districts of Noakhali in the Chittagong Division of Bengal in October–November 1946, a year before India's independence from British rule.

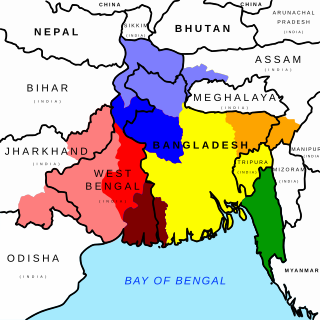

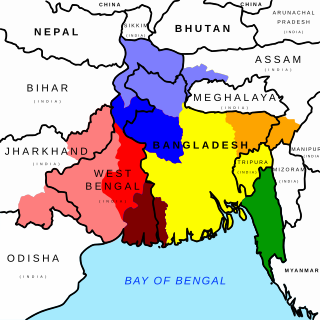

Bengali Hindus are an ethnoreligious population who make up the majority in the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Jharkhand, and Assam's Barak Valley region. In Bangladesh, they form the largest minority. They are adherents of Hinduism and are native to the Bengal region in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent. Comprising about one-third of the global Bengali population, they are the largest ethnic group among Hindus. Bengali Hindus speak Bengali, which belongs to the Indo-Aryan language family and adhere to Shaktism or Vaishnavism of their native religion Hinduism with some regional deities. There are significant numbers of Bengali-speaking Hindus in different Indian states.

The 1950 East Pakistan riots took place between Hindus and Muslims in East Pakistan, which resulted in several thousands of Hindus being killed in pogroms.

Maniram Dutta Baruah, popularly known as Maniram Dewan, was an Assamese nobleman in British India. He was one of the first people to establish tea gardens in Assam. While he was a loyal ally of the British East India Company in his early years, later he was hanged by the British for conspiring against them during the 1857 uprising. He was popular among the people of Upper Assam as "Kalita Raja".

Kamrupi dialects are a group of regional dialects of Assamese, spoken in the Kamrup region. It formerly enjoyed prestige status. It is one of two western dialect groups of the Assamese language, the other being Goalpariya. Kamrupi is heterogeneous with three subdialects— Barpetia dialect, Nalbariya dialect and Palasbaria dialect.

Bongal Kheda (trans. "Drive out the Bengalis was a xenophobic movement in Assam, India, orchestrated by native Assamese job seekers which aimed to purge out non-native job competitors — primarily, middle-class Hindu Bengalis. SooAssam has long been anti-Bengali. n after the Independence of India, the Assamese Hindu middle class gained political control in Assam and tried to gain social and economic parity with their competitors, the Bengali Hindu middle class. A significant period of property damage, ethnic policing and even instances of street violence occurred in the region. The exact timeline is disputed, though many authors agree the 1960s saw a height of disruption. It was part of a broader discontent within Assam that would foreshadow the Assamese Language Movement and the anti-Bangladeshi Assam Movement.

Bongal is a term used in Assam to refer to outsiders. Assam has been settled by colonial officials (amlahs) from Bengal pre-Independence and Hindu Bengali refugees in the post-Independence periods. The Muslims peasants from East Bengal settled in Assam are now referred to as Miya. The term lent the name to the Bongal Kheda movement of the 1950s and 1960s which sought to drive out non-Assamese competitors and to secure jobs for the natives.

Assam has a rich and complex history of Islam that dates back over 700 years. After the earlier Burmese Muslims and Sindhi or Indian Muslims converted to Islam, after them Assam has significant place on earlier conversion. The majority of Muslims in Assam are associated with the traditional culture and society of ancient India, with about 10.67% of the population identifying as Muslim, the second largest religion in the Republic of India. There are two main types of Islam in Assam: Shia Islam, which is practiced by about 1.5% of Muslims, and Sunni Islam, which is practiced by about 98.5% of Muslims, including Bengali Muslims, Kabuli Muslims, Ahom or Assamese Muslims, and All India Caste Muslims, with many of them being followers and representatives of the multi-party movement Nadwatul Ulama, Deobandi, Jamiat, Tablighi Jamaat. There are also some Muslims, many of whom are not religious believers or followers (non-practising). Muslims live in a total of Fifteen districts in the state of Assam.

Silapathar massacre refers to the massacre of Bengali Hindu refugee settlers from East Pakistan in Silapathar in undivided Lakhimpur district of Assam in February 1983. Around fifty Bengali Hindus were killed in the massacre. Veteran journalist Sabita Goswami reminisced that according to Government sources, more than a thousand people were killed in the clashes. The Hajongs, another refugee group though not the primary target, suffered casualties. The news of the massacre was reported after several days as the attackers had destroyed several bridges leading to the remote area.

The Khoirabari massacre was an ethnic massacre of an estimated 100 to 500 immigrant Bengalis in the Khoirabari area of Assam, India, on 7 February 1983. Activists of the Assam Agitation sought to block an assembly election that day and had cut communications to the Bengali enclaves, which were perceived to be pro-election. Indigenous Assamese groups, who held resentments towards the immigrant Bengalis, took advantage of the resulting isolation and surrounded and attacked the Bengali villages at night.

North Kamrup violence was a series of violent activities in North Kamrup, Assam, on 4–5 January 1980 between those who supported the Assam Movement and those who opposed it. Triggered by the death of a high school student, a member of the AASU, it led to a series of attacks and counter-attacks between Assamese and immigrant villages leading to a curfew.

The Miya people, alternatively identified as Na-Asamiya by themselves, denote the progeny of Bangladeshi Bengali Muslim migrants originating from the contemporary Mymensingh, Rangpur, and Rajshahi Divisions. These individuals established residence in the Brahmaputra Valley during the 20th century, coinciding with the period of British colonial rule in Assam. The migration of the Miya people was actively promoted by the Colonial British Government from the Bengal Province, spanning the years 1757 to 1942. This migratory trend persisted until the year 1947. Presently, the term "Miya" is employed as a discriminatory label.

In May 1948, widespread rioting broke out in Guwahati and adjoining areas where Bengali Hindu businesses, schools and residences in general and Bengali Hindu staff of the Bengal and Assam Railway in particular were attacked. The Assamese Hindu nationalists who saw the Bengali Hindus as foreign usurpers in the territory of Assam led the attacks while Muslim League members joined them. The Bengali Hindus were looted and their properties were looted and set on fire. No Bengali-speaking Muslim was attacked, as they were seen as Na Asamiyas who had adopted Assamese language and culture and therefore assimilated in the land Assam. The Guwahati riots mark the beginning of the Bongal Kheda movement.

The Bengali Hindus are the second-largest ethno-religious group just after Assamese Hindus in Assam. As per as estimation research, around 6–7.5 million Bengali Hindus live in Assam as of 2011, majority of whom live in Barak Valley and a significant population also resides in mainland Brahmaputra Valley. The Bengali Hindus are today mostly concentrated in the Barak Valley region, and now are politically, economically and socially dominant. Assam hosts the second-largest Bengali Hindu population in India after West Bengal.

Anti-Bengali sentiment comprises negative attitudes and views on Bengalis. This sentiment is present in several parts of India: Gujarat, Bihar, Assam, and various tribal areas. etc. Issues include discrimination in inhabitation, other forms of discrimination, political reasons, government actions, anti-Bangladeshi sentiment, etc. The discriminative condition of Bengalis can be traced from Khoirabari massacre, Nellie massacre, Silapathar massacre, North Kamrup massacre, Goreswar massacre, Bongal Kheda, etc. This has led to emergence of Bengali sub-nationalism in India as a form of protest and formation of many pro-Bengali organisations in India.