Related Research Articles

The human genome is a complete set of nucleic acid sequences for humans, encoded as DNA within the 23 chromosome pairs in cell nuclei and in a small DNA molecule found within individual mitochondria. These are usually treated separately as the nuclear genome and the mitochondrial genome. Human genomes include both protein-coding DNA sequences and various types of DNA that does not encode proteins. The latter is a diverse category that includes DNA coding for non-translated RNA, such as that for ribosomal RNA, transfer RNA, ribozymes, small nuclear RNAs, and several types of regulatory RNAs. It also includes promoters and their associated gene-regulatory elements, DNA playing structural and replicatory roles, such as scaffolding regions, telomeres, centromeres, and origins of replication, plus large numbers of transposable elements, inserted viral DNA, non-functional pseudogenes and simple, highly repetitive sequences. Introns make up a large percentage of non-coding DNA. Some of this non-coding DNA is non-functional junk DNA, such as pseudogenes, but there is no firm consensus on the total amount of junk DNA.

Genome projects are scientific endeavours that ultimately aim to determine the complete genome sequence of an organism and to annotate protein-coding genes and other important genome-encoded features. The genome sequence of an organism includes the collective DNA sequences of each chromosome in the organism. For a bacterium containing a single chromosome, a genome project will aim to map the sequence of that chromosome. For the human species, whose genome includes 22 pairs of autosomes and 2 sex chromosomes, a complete genome sequence will involve 46 separate chromosome sequences.

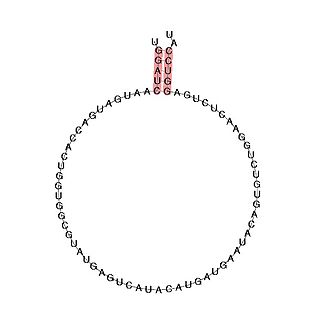

An Alu element is a short stretch of DNA originally characterized by the action of the Arthrobacter luteus (Alu) restriction endonuclease. Alu elements are the most abundant transposable elements, containing over one million copies dispersed throughout the human genome. Alu elements were thought to be selfish or parasitic DNA, because their sole known function is self reproduction. However, they are likely to play a role in evolution and have been used as genetic markers. They are derived from the small cytoplasmic 7SL RNA, a component of the signal recognition particle. Alu elements are highly conserved within primate genomes and originated in the genome of an ancestor of Supraprimates.

Comparative genomics is a field of biological research in which the genomic features of different organisms are compared. The genomic features may include the DNA sequence, genes, gene order, regulatory sequences, and other genomic structural landmarks. In this branch of genomics, whole or large parts of genomes resulting from genome projects are compared to study basic biological similarities and differences as well as evolutionary relationships between organisms. The major principle of comparative genomics is that common features of two organisms will often be encoded within the DNA that is evolutionarily conserved between them. Therefore, comparative genomic approaches start with making some form of alignment of genome sequences and looking for orthologous sequences in the aligned genomes and checking to what extent those sequences are conserved. Based on these, genome and molecular evolution are inferred and this may in turn be put in the context of, for example, phenotypic evolution or population genetics.

Indel (insertion-deletion) is a molecular biology term for an insertion or deletion of bases in the genome of an organism. Indels ≥ 50 bases in length are classified as structural variants.

In evolutionary biology, conserved sequences are identical or similar sequences in nucleic acids or proteins across species, or within a genome, or between donor and receptor taxa. Conservation indicates that a sequence has been maintained by natural selection.

The Chimpanzee Genome Project was an effort to determine the DNA sequence of the chimpanzee genome. Sequencing began in 2005 and by 2013 twenty-four individual chimpanzees had been sequenced. This project was folded into the Great Ape Genome Project.

Human evolutionary genetics studies how one human genome differs from another human genome, the evolutionary past that gave rise to the human genome, and its current effects. Differences between genomes have anthropological, medical, historical and forensic implications and applications. Genetic data can provide important insights into human evolution.

Transcriptional repressor CTCF also known as 11-zinc finger protein or CCCTC-binding factor is a transcription factor that in humans is encoded by the CTCF gene. CTCF is involved in many cellular processes, including transcriptional regulation, insulator activity, V(D)J recombination and regulation of chromatin architecture.

In molecular biology, SNORD115 is a non-coding RNA (ncRNA) molecule known as a small nucleolar RNA which usually functions in guiding the modification of other non-coding RNAs. This type of modifying RNA is usually located in the nucleolus of the eukaryotic cell which is a major site of snRNA biogenesis. HBII-52 refers to the human gene, whereas RBII-52 is used for the rat gene and MBII-52 is used for naming the mouse gene.

Probable G-protein coupled receptor 85 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the GPR85 gene.

Sodium-coupled neutral amino acid transporter 3 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the SLC38A3 gene.

AT-rich interactive domain-containing protein 2 (ARID2) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ARID2 gene.

DGLUCY is a protein that in humans is encoded by the DGLUCY gene.

Protein ITFG3 also known as family with sequence similarity 234 member A (FAM234A) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ITFG3 gene. Here, the gene is explored as encoded by mRNA found in Homo sapiens. The FAM234A gene is conserved in mice, rats, chickens, zebrafish, dogs, cows, frogs, chimpanzees, and rhesus monkeys. Orthologs of the gene can be found in at least 220 organisms including the tropical clawed frog, pandas, and Chinese hamsters. The gene is located at 16p13.3 and has a total of 19 exons. The mRNA has a total of 3224 bp and the protein has 552 aa. The molecular mass of the protein produced by this gene is 59660 Da. It is expressed in at least 27 tissue types in humans, with the greatest presence in the duodenum, fat, small intestine, and heart.

Long non-coding RNAs are a type of RNA, generally defined as transcripts more than 200 nucleotides that are not translated into protein. This arbitrary limit distinguishes long ncRNAs from small non-coding RNAs, such as microRNAs (miRNAs), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs), and other short RNAs. Given that some lncRNAs have been reported to have the potential to encode small proteins or micro-peptides, the latest definition of lncRNA is a class of RNA molecules of over 200 nucleotides that have no or limited coding capacity. Long intervening/intergenic noncoding RNAs (lincRNAs) are sequences of lncRNA which do not overlap protein-coding genes.

In molecular biology, Small nucleolar RNA SNORD113 is a small nucleolar RNA molecule which is located in the imprinted human 14q32 locus and may play a role in the evolution and/or mechanism of the epigenetic imprinting process.

A conserved non-coding sequence (CNS) is a DNA sequence of noncoding DNA that is evolutionarily conserved. These sequences are of interest for their potential to regulate gene production.

An ultra-conserved element (UCE) was originally defined as a genome segment longer than 200 base pairs (bp) that is absolutely conserved, with no insertions or deletions and 100% identity, between orthologous regions of the human, rat, and mouse genomes. 481 ultra-conserved elements have been identified in the human genome. If ribosomal DNA are excluded, these range in size from 200 bp to 781 bp. UCRs are found on all chromosomes except for 21 and Y. A database collecting genomic information about ultra-conserved elements (UCbase) is available at http://ucbase.unimore.it.

Donna R. Maglott is a staff scientist at the National Center for Biotechnology Information known for her research on large-scale genomics projects, including the mouse genome and development of databases required for genomics research.

References

- 1 2 Woolfe, A.; Goodson, M.; Goode, D. K.; Snell, P.; McEwen, G. K.; Vavouri, T.; Smith, S. F.; North, P.; Callaway, H.; Kelly, K.; Walter, K.; Abnizova, I.; Gilks, W.; Edwards, Y. J. K.; Cooke, J. E.; Elgar, G. (2005). "Highly Conserved Non-Coding Sequences Are Associated with Vertebrate Development". PLOS Biology. 3 (1): e7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030007 . PMC 526512 . PMID 15630479.

- ↑ Dermitzakis, E. T.; Reymond, A.; Scamuffa, N.; Ucla, C.; Kirkness, E.; Rossier, C.; Antonarakis, S. E. (2003). "Evolutionary Discrimination of Mammalian Conserved Non-Genic Sequences (CNGs)". Science. 302 (5647): 1033–1035. Bibcode:2003Sci...302.1033D. doi: 10.1126/science.1087047 . PMID 14526086. S2CID 35299360.

- 1 2 McLean, C. Y.; Reno, P. L.; Pollen, A. A.; Bassan, A. I.; Capellini, T. D.; Guenther, C.; Indjeian, V. B.; Lim, X.; Menke, D. B.; Schaar, B. T.; Wenger, A. M.; Bejerano, G.; Kingsley, D. M. (2011). "Human-specific loss of regulatory DNA and the evolution of human-specific traits". Nature. 471 (7337): 216–9. Bibcode:2011Natur.471..216M. doi:10.1038/nature09774. PMC 3071156 . PMID 21390129.

- ↑ Chen, R.; Bouck, J. B.; Weinstock, G. M.; Gibbs, R. A. (2001). "Comparing Vertebrate Whole-Genome Shotgun Reads to the Human Genome". Genome Research. 11 (11): 1807–1816. doi:10.1101/gr.203601. PMC 311156 . PMID 11691844.

- ↑ Harris, R. A.; Rogers, J.; Milosavljevic, A. (2007). "Human-Specific Changes of Genome Structure Detected by Genomic Triangulation". Science. 316 (5822): 235–237. Bibcode:2007Sci...316..235H. doi: 10.1126/science.1139477 . PMID 17431168.

- ↑ Gibbs, R. A.; Gibbs, J.; Rogers, M. G.; Katze, R.; Bumgarner, G. M.; Weinstock, E. R.; Mardis, K. A.; Remington, R. L.; Strausberg, J. C.; Venter, R. K.; Wilson, M. A.; Batzer, C. D.; Bustamante, E. E.; Eichler, M. W.; Hahn, R. C.; Hardison, K. D.; Makova, W.; Miller, A.; Milosavljevic, R. E.; Palermo, A.; Siepel, J. M.; Sikela, T.; Attaway, S.; Bell, K. E.; Bernard, C. J.; Buhay, M. N.; Chandrabose, M.; Dao, C.; Davis, K. D.; et al. (2007). "Evolutionary and Biomedical Insights from the Rhesus Macaque Genome". Science. 316 (5822): 222–234. Bibcode:2007Sci...316..222.. doi: 10.1126/science.1139247 . PMID 17431167.

- ↑ Schwartz, S.; Kent, W. J.; Smit, A.; Zhang, Z.; Baertsch, R.; Hardison, R. C.; Haussler, D.; Miller, W. (2003). "Human–Mouse Alignments with BLASTZ". Genome Research. 13 (1): 103–107. doi:10.1101/gr.809403. PMC 430961 . PMID 12529312.

- ↑ Blanchette, M.; Kent, W. J.; Riemer, C.; Elnitski, L.; Smit, A. F.; Roskin, K. M.; Baertsch, R.; Rosenbloom, K.; Clawson, H.; Green, E. D.; Haussler, D.; Miller, W. (2004). "Aligning Multiple Genomic Sequences with the Threaded Blockset Aligner". Genome Research. 14 (4): 708–715. doi:10.1101/gr.1933104. PMC 383317 . PMID 15060014.

- ↑ Green, R. E.; Krause, J.; Briggs, A. W.; Maricic, T.; Stenzel, U.; Kircher, M.; Patterson, N.; Li, H.; Zhai, W.; Fritz, M. H. Y.; Hansen, N. F.; Durand, E. Y.; Malaspinas, A. S.; Jensen, J. D.; Marques-Bonet, T.; Alkan, C.; Prüfer, K.; Meyer, M.; Burbano, H. A.; Good, J. M.; Schultz, R.; Aximu-Petri, A.; Butthof, A.; Höber, B.; Höffner, B.; Siegemund, M.; Weihmann, A.; Nusbaum, C.; Lander, E. S.; Russ, C. (2010). "A Draft Sequence of the Neandertal Genome". Science. 328 (5979): 710–722. Bibcode:2010Sci...328..710G. doi:10.1126/science.1188021. PMC 5100745 . PMID 20448178.

- ↑ Musto, H.; Cacciò, S.; Rodríguez-Maseda, H.; Bernardi, G. (1997). "Compositional constraints in the extremely GC-poor genome of Plasmodium falciparum". Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 92 (6): 835–841. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02761997000600020 . PMID 9566216.

- ↑ Levy, S.; Hannenhalli, S.; Workman, C. (2001). "Enrichment of regulatory signals in conserved non-coding genomic sequence". Bioinformatics. 17 (10): 871–877. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.10.871 . PMID 11673231.

- ↑ Suzuki, R.; Saitou, N. (2011). "Exploration for Functional Nucleotide Sequence Candidates within Coding Regions of Mammalian Genes". DNA Research. 18 (3): 177–187. doi:10.1093/dnares/dsr010. PMC 3111233 . PMID 21586532.

- ↑ Chou, H. -H.; Takematsu, H.; Diaz, S.; Iber, J.; Nickerson, E.; Wright, K. L.; Muchmore, E. A.; Nelson, D. L.; Warren, S. T.; Varki, A. (1998). "A mutation in human CMP-sialic acid hydroxylase occurred after the Homo-Pan divergence". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 95 (20): 11751–11756. Bibcode:1998PNAS...9511751C. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11751 . PMC 21712 . PMID 9751737.

- ↑ Poulin, F.; Nobrega, M. A.; Plajzer-Frick, I.; Holt, A.; Afzal, V.; Rubin, E. M.; Pennacchio, L. A. (2005). "In vivo characterization of a vertebrate ultraconserved enhancer" (PDF). Genomics. 85 (6): 774–781. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.03.003. PMID 15885503. S2CID 21888183.

- ↑ Gotea, V.; Visel, A.; Westlund, J. M.; Nobrega, M. A.; Pennacchio, L. A.; Ovcharenko, I. (2010). "Homotypic clusters of transcription factor binding sites are a key component of human promoters and enhancers". Genome Research. 20 (5): 565–577. doi:10.1101/gr.104471.109. PMC 2860159 . PMID 20363979.

- ↑ Hill, R. S.; Walsh, C. A. (2005). "Molecular insights into human brain evolution". Nature. 437 (7055): 64–67. Bibcode:2005Natur.437...64H. doi:10.1038/nature04103. PMID 16136130. S2CID 4406401.