Early life and education

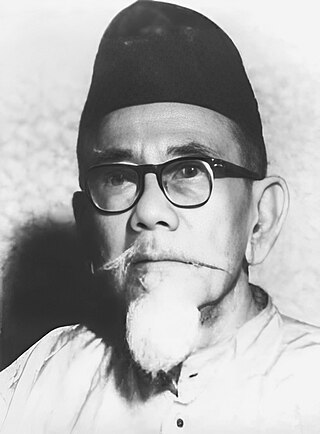

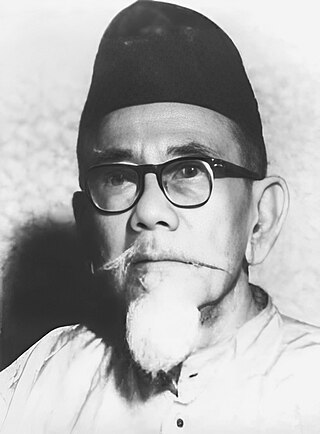

Hausman Baboe was born in Hampatong village in the Kuala Kapuas, a town that is now the capital of Kapuas Regency. There are conflicting sources for his birth year; possible dates include 1880, 1881, and 1885. [3] [4] [2] He was born to an Utus Gantung family, an aristocratic class of the Ngaju people. [3] [4] Hampatong village was founded as a result of the outbreak of the Banjarmasin War in 1859, causing a mass exodus from villages near the Mangkatip River, a tributary of the Barito River. Hampatong was inhabited mostly by aristocrat families of the Dayak Ngaju people and Christian missionaries nicknamed it kampong adligendrof (village of nobles). As a result of being born an aristocrat, Baboe and his family enjoyed a relatively privileged life compared to the general population of the region. [2] [3]

Baboe's father Yoesoea Baboe was married to Soemboel, the daughter of a village chief. The couple had nine children, including Baboe. Most of Hausman's siblings left the village after their marriages. Hausman Baboe worked as a colonial administrator and frequently travelled around Kalimantan. He married a woman named Reginae and had eight children. [2] Some sources, however, say he later married a second woman of Banjar ethnicity, [2] whom he later divorced. According to these sources, this second marriage brought him a child named Roeslan Baboe, for whom Baboe and Reginae cared. [3] [5]

Baboe was educated by Christian missionaries. It is unclear if he ever pursued higher education due to a lack of records. He was appointed as head of the Kuala Kapuas district despite it being unclear if he fulfilled the requirements to do so, such as receiving a higher education. Heads of districts usually needed to be graduates of OSVIA (Opleiding School Voor Inlandsche Ambtenaren), the indigenous civil-servant school. [3] Indonesian historians speculated Baboe was appointed due to his aristocratic status and because his grandfather Nikodemus Ambo was also a district chief. [3] [6] [2] In 1905, Baboe started to work as a journalist for the newspaper Sinar Borneo; he also worked as a district chief between 1919 and 1922. [4]

Political career

Hausman Baboe was inspired by early contemporaneous political movements and organizations in Surabaya, and argued for the establishment of Pakat Dayak, a Dayak-based political organization similar to those of Sarekat Islam and Indische Party. [7] In February 1922, Baboe was dismissed from his job as district chief due to his increasingly anti-colonial remarks, and Pakat Dayak's support for a Sarekat Islam insurrection in Sampit and Pangkalan Bun. [8]

In 1920, Baboe established a cooperative under Pakat Dayak. He was described by missionary records as "susceptible to communist ideas" [8] and, due to his political activities, was placed under tight government surveillance. [9] In 1924, Baboe founded a school for Dayak called Hollandsche Dajak School, which was used to spread nationalist ideas among Dayak youths. [7] He continued to help Sarekat Islam, spreading its political activities across Kalimantan; he also founded another private school in Mentangai. [8] In Java, Baboe became friends with Oemar Said Tjokroaminoto, the chairman of Sarekat Islam. [7] Briefly after Tjokroaminoto's release and his rumoured plan to visit Kalimantan, Baboe mobilized Dayak political organizations such as Serikat Dajak, another Dayak organization, to distribute pamphlets about the visit to the interior Dayak populations. The goal was to rally political support behind Tjokroaminoto and spread anti-government ideas. [8] As a result of unrest following Tjokroaminoto's actions, the government banned Tjokroaminoto from visiting Kalimantan and placed a travel ban across Kalimantan to limit the spread of Baboe's pamphlets. The travel ban proved to be ineffective. [8]

In 1923, Baboe together with many Dayak activists established the National Borneo Council and in April that year held the National Borneo Congress in Banjarmasin. Baboe was referred to in the congress as "advisor for government affairs" for Sarekat Islam; he wrote a grievance motion to the Governor General of Dutch East Indies but this did not have the effect he had hoped for. From 1924 to 1930, Dutch colonial administrators, who were known as colonial residents, in Kalimantan routinely included mentions of Baboe in their reports, minimizing his influence and trying to assure the colonial government in Batavia he was not a significant threat. [2] In October 1925, Baboe gave speech to around 200 Christian Dayaks in Kuala Kapuas regarding land rights, women's status, and urging native Kalimantan people to join labour unions. He also argued villagers should grow vegetables and fruits rather than rubber, arguing for the abolition of the slaughter tax, and arguing in favour of cooperation between the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) and Sarekat Islam in Java. Newspapers in Banjarmasin later reported his meeting as a communist activity. [2]

In 1925, both Sarekat Islam and Sarekat Dajak made another attempt to invite Tjokroaminoto to Kalimantan; they also invited Agus Salim. Later, as the chairman of Sarekat Dajak, Baboe co-wrote the invitation with Mohamad Arip and Mohamad Horman of Sarekat Islam. As a result, the colonial government again banned the invited figures from Java from entering Kalimantan but the congress under Sarekat Dajak was still held, mainly focusing on the land tax and forced labour. In December 1926, Baboe and Sarekat Dajak led another National Borneo Congress. He also started to argue for Dayak representation in the Volksraad, and that the absence of secondary schools in Dayak districts showed the Dutch administration was discriminating against Dayaks.

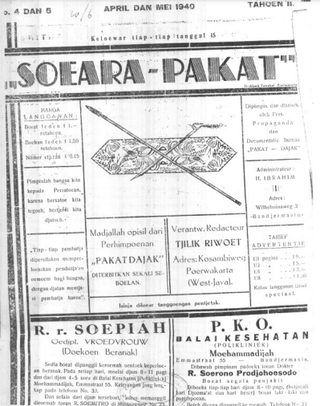

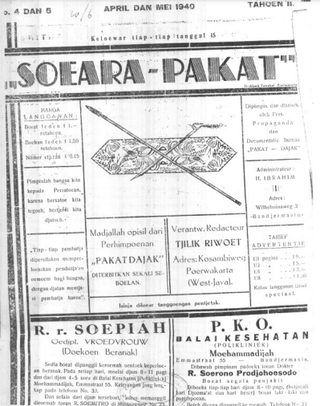

Two months before the 1926 National Borneo Congress, Baboe established Suara Borneo, a newspaper with strong Indonesian nationalist sentiments. His newspaper was short-lived, mainly due to lack of funding and because the colonial government in Banjarmasin expelled its editor Achmad for communist tendencies. [2] Achmad, a teacher and activist from East Java, was affiliated with Sarekat Rakjat and PKI. He was exiled to Kalimantan in 1925 and was befriended by Baboe the next year. Fearing a nationwide communist revolt and to separate him from Baboe, police sent Achmad back to Java in November 1926 under pretext of facing trial. Suara Borneo later wrote Achmad's detention proved he was doing the right thing. [2]

Suara Borneo mostly attracted readers from the urban Dayaks and Malays in Banjarmasin, and reached some readers as far away as Makassar. The newspaper was marked by ideas of the Indonesian National Awakening, that all ethnic identities should see all of themselves as part of a whole and that all Indonesian people "were united in the same fate". Baboe named the first edition of his newspaper "Progress", and urged readers to subscribe and submit news to the newspaper as long as it was not slanderous or about religion. His writing moved away from land rights and taxes, mostly relevant only to Dayaks, towards identity issues, challenging the "savage stereotypes" often used against Indonesian ethnicities such as the Dayaks and Madurese. [2] Baboe was criticized by Bingkisan, another progressive newspaper based in Banjarmasin, which said his criticism of colonial governments was often too polite and soft. Gerry van Klinken, researcher of Dayak political history, said Baboe's moderation was due to his age—by that time he was older than most Indonesian nationalist leaders—and because he was relatively wealthy. [2]

Legacy

Hausman Baboe is regarded as an early figure who brought native Kalimantan, and especially Dayak, participation in the Indonesian nationalist movement. His organizations such as Sarekat Dajak later became the foundation of Dayak political movements in Kalimantan and Indonesia. He was also a pioneer of journalism in Kalimantan. [10] Together with George Obus and Tjilik Riwut, Baboe is regarded as a pioneer of the nationalist movement in what is today Central Kalimantan, and he was crucial for the spread of Indonesian nationalism within Kalimantan. Baboe's ideas led to the creation of Central Kalimantan province in 1957. [11]

In November 1938, Dayak political movements again tried to be appointed to the Volksraad under the name "Committee for Dayak Tribal Awareness". Its members, who were led by Baboe's nephew Mahir Mahar, were civil servants who had been educated as students and teachers at Baboe's schools. [2] One of his sons Ruslan Baboe later became a prominent Indonesian diplomat, working as a consul for Indonesia in San Francisco, and later as Indonesian ambassador to Hungary between 1970 and 1974. [3]

A street in Palangka Raya is named after Hausman Baboe. [2] [3]

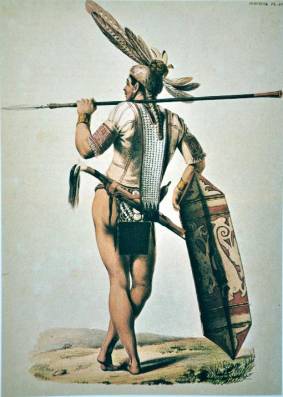

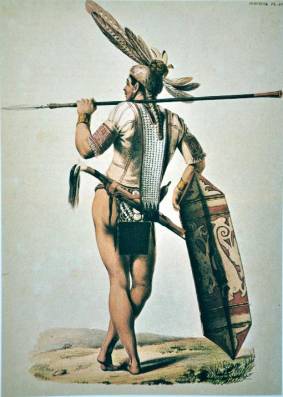

The Dayak or Dyak or Dayuh are one of the native groups of Borneo. It is a loose term for over 200 riverine and hill-dwelling ethnic groups, located principally in the central and southern interior of Borneo, each with its own dialect, customs, laws, territory, and culture, although common distinguishing traits are readily identifiable. The Dayak were animist in belief; however, since the 19th century there has been mass conversion to Christianity as well as Islam due to the spreading of Abrahamic religions.

South Kalimantan is a province of Indonesia. It is the smallest province in Kalimantan, the Indonesian territory of the island of Borneo. The provincial capital was Banjarmasin until 15 February 2022 when it was legally moved 35 kms southeast to Banjarbaru. The population of South Kalimantan was recorded at just over 3.625 million people at the 2010 Census, and at 4.07 million at the 2020 Census. The official estimate as at mid 2023 was 4,221,929. One of the five Indonesian provinces in Kalimantan, it is bordered by the Makassar Strait in the east, Central Kalimantan in the west and north, the Java Sea in the south, and East Kalimantan in the northeast. The province also includes the island of Pulau Laut, located off the eastern coast of Kalimantan, as well as other smaller offshore islands. The province is divided into 11 regencies and 2 cities. South Kalimantan is the traditional homeland of the Banjar people, although some parts of East Kalimantan and Central Kalimantan are also included in this criterion. Nevertheless, South Kalimantan, especially the former capital city Banjarmasin has always been the cultural capital of Banjarese culture. Many Banjarese have migrated to other parts of Indonesia, as well as neighbouring countries such as Singapore and Malaysia. In addition, other ethnic groups also inhabit the province, such as several groups of the Dayaks, who mostly live in the interior part of the province, as well as the Javanese, who mostly migrated from Java due to the Transmigration program which dated from the Dutch colonial era. It is one of the provinces in Indonesia that has a larger population than Mongolia.

The Communist Party of Indonesia was a communist party in the Dutch East Indies and later Indonesia. It was the largest non-ruling communist party in the world before its violent disbandment in 1965. The party had two million members in the 1955 elections, with 16 percent of the national vote and almost 30 percent of the vote in East Java. During most of the period immediately following the Indonesian Independence until the eradication of the PKI in 1965, it was a legal party operating openly in the country. After 1965, the party has since been declared as illegal and its activities are considered treason and terrorist by the Indonesian government.

Banjarmasin is a city in South Kalimantan, Indonesia. It was the capital of the province until 15 February 2022. The city is located on a delta island near the junction of the Barito and Martapura rivers. Historically the centre of the Banjarese culture, and the capital of the Sultanate of Banjar, it is the biggest city in South Kalimantan and one of the main cities of Kalimantan. The city covers an area of 98.46 km2 (38.02 sq mi) and had a population of 625,481 as of the 2010 Census and 657,663 as of the 2020 Census; the official estimate as of mid 2023 was 675,915. It is the third most populous city on the island of Borneo.

Semaun (1899–1971), also spelled Semaoen, was the first chairman of the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) and was a leader of the Semarang branch of the Sarekat Islam.

Negara Daha was a Hindu kingdom successor of Negara Dipa that appears in the Hikayat Banjar. It was located in what is now the Regency of Hulu Sungai Selatan, Province of South Kalimantan, Republic of Indonesia.

Sarekat Islam or Syarikat Islam was an Indonesian socio-political organization founded at the beginning of the 20th century during the Dutch colonial era. Initially, SI served as a cooperative of Muslim Javanese batik traders to compete with the Chinese-Indonesian big traders. From there, SI rapidly evolved into a nationalist political organization that demanded self-governance against the Dutch colonial regime and gained wide popular support. SI was especially active during the 1910s and the early 1920s. By 1916, it claimed 80 branches with a total membership of around 350,000.

The Banjar or Banjarese are an Austronesian ethnic group native to the Banjar regions in the southeastern Kalimantan regions of Indonesia. Nowadays, Banjarese diaspora can be found in neighbouring Banjar regions as well; including Kotabaru Regency, the southeastern regions of Central Kalimantan, southernmost regions of East Kalimantan, and some provinces of Indonesia in general. The Banjarese diaspora community also can be found in neighbouring countries of Indonesia, such as Brunei, Malaysia, and Singapore.

HajiAgus Salim was an Indonesian journalist, diplomat, and statesman. He served as Indonesia's Minister of Foreign Affairs between 1947 and 1949.

Oemar Said Tjokroaminoto, better known in Indonesia as H.O.S. Tjokroaminoto, was an Indonesian nationalist. He became one of the leaders of the Islamic Trade Union, founded by Samanhudi, which became Sarekat Islam, which they both cofounded.

Indonesian Islamic Union Party was an Islamic political party in Indonesia before and after independence. In 1973 it was merged into the United Development Party.

The Ngaju people are an indigenous ethnic group of Borneo from the Dayak group. In a census from 2000, when they were first listed as a separate ethnic group, they made up 18.02% of the population of Central Kalimantan province. In an earlier census from 1930, the Ngaju people were included in the Dayak people count. They speak the Ngaju language.

Bakumpai or Baraki are indigenous people of Borneo and are considered as a sub-ethnic group of the Dayak Ngaju people group with Islamic background. The Bakumpai people first occupy along the Barito riverbanks in South Kalimantan and Central Kalimantan, from Marabahan to Puruk Cahu, Murung Raya Regency. The Bakumpai people first appeared as a newly recognized people group in census 2000 and were made up of 7.51% of Central Kalimantan population, which before this the Bakumpai people were considered as part of the Dayak people in a 1930 census.

Johanes Chrisostomus Oevaang Oeray was an Indonesian politician. He was the Governor of West Kalimantan from 1960 to 1966; he was the first ethnic Dayak to hold the position.

Great Dayak was a component entity of the United States of Indonesia in Dayak regions on the island of Borneo. It was established on 7 December 1946 with a temporary capital at Bandjermasin (Banjarmasin). Great Dayak was dissolved on 18 April 1950 and became part of Kalimantan Province which was formed on 14 August 1950 with its capital also at Banjarmasin. Following the division of Kalimantan Province, the former territory of Great Dayak was assigned first to South Kalimantan in 1956 and then Central Kalimantan in 1957 where it remains today.

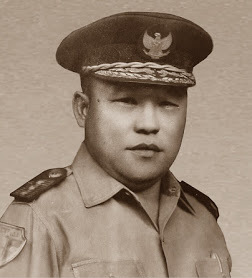

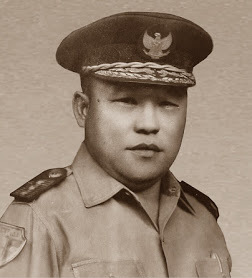

Hasan Basry was a military general, Indonesian nationalist leader, and was a key figure in the liberation of Kalimantan from Dutch rule. During the Indonesian National Revolution, he acted as the military representative of the Indonesian army in Kalimantan and led a guerilla war against the Linggadjati Agreement. He was a key figure behind the 17 May Proclamation which rallied Kalimantan natives against Dutch rule in 1949. He was declared a National Hero of Indonesia in 2001.

Anakletus Tjilik Riwut was an Indonesian military officer and journalist who served as the governor of Central Kalimantan from 1959 to 1967. He participated in the Indonesian National Revolution, becoming one of the leaders of the Kalimantan Physical Revolution in Dutch Borneo. In 1988, the government of Indonesia declared him a national hero.

Mohammad Misbach, commonly known as Haji Misbach, was a communist and Islamic activist from Surakarta, Dutch East Indies. He was a leading member of the left wing of the Sarekat Islam organization in the 1910s and famously advocated for the compatibility of Islam and communism.

Mandau Talawang Pancasila is a paramilitary organization, based mostly within the Indonesian provinces of Central Kalimantan and West Kalimantan.

Dayak in politics refers to the participation of Dayaks to represent their political ideas and interests outside of their community. The movement has continued to have a profound impact on the development of Indonesia and Malaysia, especially in Kalimantan and Sarawak.