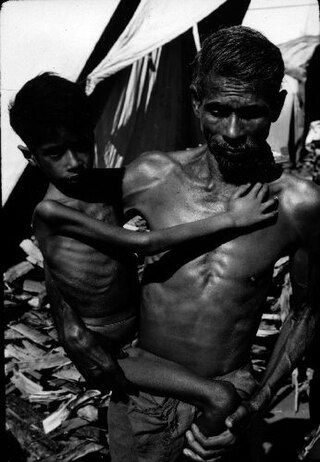

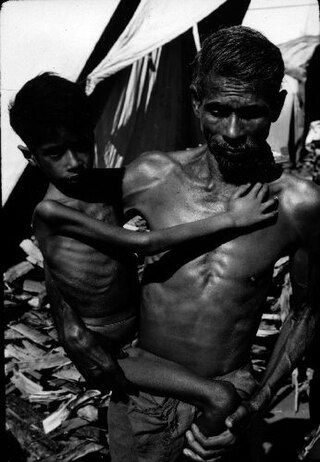

Marasmus is a form of severe malnutrition characterized by energy deficiency. It can occur in anyone with severe malnutrition but usually occurs in children. Body weight is reduced to less than 62% of the normal (expected) body weight for the age. Marasmus occurrence increases prior to age 1, whereas kwashiorkor occurrence increases after 18 months. It can be distinguished from kwashiorkor in that kwashiorkor is protein deficiency with adequate energy intake whereas marasmus is inadequate energy intake in all forms, including protein. This clear-cut separation of marasmus and kwashiorkor is however not always clinically evident as kwashiorkor is often seen in a context of insufficient caloric intake, and mixed clinical pictures, called marasmic kwashiorkor, are possible. Protein wasting in kwashiorkor generally leads to edema and ascites, while muscular wasting and loss of subcutaneous fat are the main clinical signs of marasmus, which makes the ribs and joints protrude.

Health in Uganda refers to the health of the population of Uganda. The average life expectancy at birth of Uganda has increased from 59.9 years in 2013 to 63.4 years in 2019. This is lower than in any other country in the East African Community except Burundi. As of 2017, females had a life expectancy higher than their male counterparts of 69.2 versus 62.3. It is projected that by 2100, males in Uganda will have an expectancy of 74.5 and females 83.3. Uganda's population has steadily increased from 36.56 million in 2016 to an estimate of 42.46 in 2021. The fertility rate of Ugandan women slightly increased from an average of 6.89 babies per woman in the 1950s to about 7.12 in the 1970s before declining to an estimate 5.32 babies in 2019. This figure is higher than most world regions including South East Asia, Middle East and North Africa, Europe and Central Asia and America. The under-5-mortality-rate for Uganda has decreased from 191 deaths per 1000 live births in 1970 to 45.8 deaths per 1000 live births in 2019.

India's population in 2021 as per World Bank is 1.39 billion. Being the world's second-most-populous country and one of its fastest-growing economies, India experiences both challenges and opportunities in context of public health. India is a hub for pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries; world-class scientists, clinical trials and hospitals yet country faces daunting public health challenges like child undernutrition, high rates of neonatal and maternal mortality, growth in noncommunicable diseases, high rates of road traffic accidents and other health related issues.

Diseases of poverty are diseases that are more prevalent in low-income populations. They include infectious diseases, as well as diseases related to malnutrition and poor health behaviour. Poverty is one of the major social determinants of health. The World Health Report (2002) states that diseases of poverty account for 45% of the disease burden in the countries with high poverty rate which are preventable or treatable with existing interventions. Diseases of poverty are often co-morbid and ubiquitous with malnutrition. Poverty increases the chances of having these diseases as the deprivation of shelter, safe drinking water, nutritious food, sanitation, and access to health services contributes towards poor health behaviour. At the same time, these diseases act as a barrier for economic growth to affected people and families caring for them which in turn results into increased poverty in the community. These diseases produced in part by poverty are in contrast to diseases of affluence, which are diseases thought to be a result of increasing wealth in a society.

In Nigeria, there has been a major progress in the improvement of health since 1950. Although lower respiratory infections, neonatal disorders and HIV/AIDS have ranked the topmost causes of deaths in Nigeria, in the case of other diseases such as monkeypox, polio, malaria and tuberculosis, progress has been achieved. Among other threats to health are malnutrition, pollution and road traffic accidents. In 2020, Nigeria had the highest number of cases of COVID-19 in Africa.

Tropical diseases, especially malaria and tuberculosis, have long been a public health problem in Kenya. In recent years, infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which causes acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), also has become a severe problem. Estimates of the incidence of infection differ widely.

HIV/AIDS in Eswatini was first reported in 1986 but has since reached epidemic proportions. As of 2016, Eswatini had the highest prevalence of HIV among adults aged 15 to 49 in the world (27.2%).

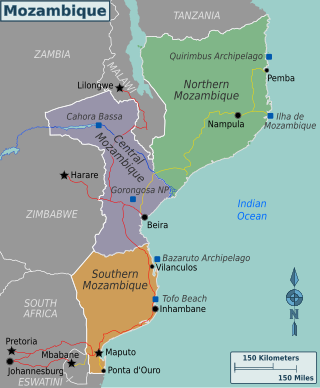

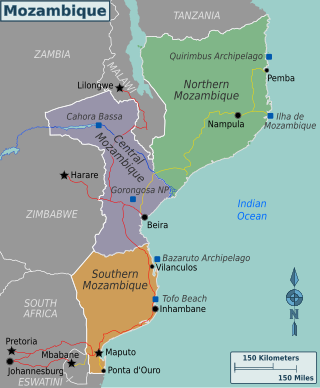

Mozambique is a country particularly hard-hit by the HIV/AIDS epidemic. According to 2008 UNAIDS estimates, this southeast African nation has the 8th highest HIV rate in the world. With 1,600,000 Mozambicans living with HIV, 990,000 of which are women and children, Mozambique's government realizes that much work must be done to eradicate this infectious disease. To reduce HIV/AIDS within the country, Mozambique has partnered with numerous global organizations to provide its citizens with augmented access to antiretroviral therapy and prevention techniques, such as condom use. A surge toward the treatment and prevention of HIV/AIDS in women and children has additionally aided in Mozambique's aim to fulfill its Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Nevertheless, HIV/AIDS has made a drastic impact on Mozambique; individual risk behaviors are still greatly influenced by social norms, and much still needs to be done to address the epidemic and provide care and treatment to those in need.

In precolonial Ghana, infectious diseases were the main cause of morbidity and mortality. The modern history of health in Ghana was heavily influenced by international actors such as Christian missionaries, European colonists, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund. In addition, the democratic shift in Ghana spurred healthcare reforms in an attempt to address the presence of infectious and noncommunicable diseases eventually resulting in the formation of the National Health insurance Scheme in place today.

The quality of health in Cambodia is rising along with its growing economy. The public health care system has a high priority from the Cambodian government and with international help and assistance, Cambodia has seen some major and continuous improvements in the health profile of its population since the 1980s, with a steadily rising life expectancy.

Health problems have been a long-standing issue limiting development in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The current population of Myanmar is 54.05 million. It was 27.27 million in 1970. The general state of healthcare in Myanmar is poor. The military government of 1962-2011 spent anywhere from 0.5% to 3% of the country's GDP on healthcare. Healthcare in Myanmar is consistently ranked among the lowest in the world. In 2015, in congruence with a new democratic government, a series of healthcare reforms were enacted. In 2017, the reformed government spent 5.2% of GDP on healthcare expenditures. Health indicators have begun to improve as spending continues to increase. Patients continue to pay the majority of healthcare costs out of pocket. Although, out of pocket costs were reduced from 85% to 62% from 2014 to 2015. They continue to drop annually. The global average of healthcare costs paid out of pocket is 32%. Both public and private hospitals are understaffed due to a national shortage of doctors and nurses. Public hospitals lack many of the basic facilities and equipment. WHO consistently ranks Myanmar among the worst nations in healthcare.

Health in Angola is rated among the worst in the world.

Botswana's healthcare system has been steadily improving and expanding its infrastructure to become more accessible. The country's position as an upper middle-income country has allowed them to make strides in universal healthcare access for much of Botswana's population. The majority of the Botswana's 2.3 million inhabitants now live within five kilometres of a healthcare facility. As a result, the infant mortality and maternal mortality rates have been on a steady decline. The country's improving healthcare infrastructure has also been reflected in an increase of the average life expectancy from birth, with nearly all births occurring in healthcare facilities.

A landlocked sub-Saharan country, Burkina Faso is among the poorest countries in the world—44 percent of its population lives below the international poverty line of US$1.90 per day —and it ranks 185th out of 188 countries on UNDP's 2016 Human Development Index .Rapid population growth, gender inequality, and low levels of educational attainment contribute to food insecurity and poverty in Burkina Faso. The total population is just over 20 million with the estimated population growth rate is 3.1 percent per year and seven out of 10 Burkinabe are younger than 30. Total health care expenditures were an estimated 5% of GDP. Total expenditure on health per capita is 82 in 2014.

Health in South Africa touches on various aspects of health including the infectious diseases, Nutrition, Mental Health and Maternal care.

The quality of health in Rwanda has historically been very low, both before and immediately after the 1994 genocide. In 1998, more than one in five children died before their fifth birthday, often from malaria. But in recent years Rwanda has seen improvement on a number of key health indicators. Between 2005 and 2013, life expectancy increased from 55.2 to 64.0, under-5 mortality decreased from 106.4 to 52.0 per 1,000 live births, and incidence of tuberculosis has dropped from 101 to 69 per 100,000 people. The country's progress in healthcare has been cited by the international media and charities. The Atlantic devoted an article to "Rwanda's Historic Health Recovery". Partners In Health described the health gains "among the most dramatic the world has seen in the last 50 years".

Life expectancy in Nicaragua at birth was 72 years for men and 78 for women in 2016. While communicable diseases such as dengue, chikungunya, and Zika continue to persist as national health concerns, there is a rising public health threat of non-communicable diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer, which were diseases previously thought to be more relevant and problematic for more developed nations. Additionally, in the women's health sector, high rates of adolescent pregnancy and cervical cancer continue to persist as national concerns.

Expenditure on health in Senegal was 4.7% of GDP in 2014, US$107 per capita.

Child health and nutrition in Africa is concerned with the health care of children through adolescents in the various countries of Africa. The right to health and a nutritious and sufficient diet are internationally recognized human rights that are protected by international treaties. Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) 1, 4, 5 and 6 highlight, respectively, how poverty, hunger, child mortality, maternal health, the eradication of HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis and other diseases are of particular significance in the context of child health.