The United States President's Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) is a United States governmental initiative to address the global HIV/AIDS epidemic and help save the lives of those suffering from the disease. Launched by U.S. President George W. Bush in 2003, as of May 2020, PEPFAR has provided about $90 billion in cumulative funding for HIV/AIDS treatment, prevention, and research since its inception, making it the largest global health program focused on a single disease in history until the COVID-19 pandemic. PEPFAR is implemented by a combination of U.S. government agencies in over 50 countries and overseen by the Global AIDS Coordinator at the United States Department of State. As of 2023, PEPFAR has saved over 25 million lives, primarily in sub-Saharan Africa.

Health in Uganda refers to the health of the population of Uganda. The average life expectancy at birth of Uganda has increased from 59.9 years in 2013 to 63.4 years in 2019. This is lower than in any other country in the East African Community except Burundi. As of 2017, females had a life expectancy higher than their male counterparts of 69.2 versus 62.3. It is projected that by 2100, males in Uganda will have an expectancy of 74.5 and females 83.3. Uganda's population has steadily increased from 36.56 million in 2016 to an estimate of 42.46 in 2021. The fertility rate of Ugandan women slightly increased from an average of 6.89 babies per woman in the 1950s to about 7.12 in the 1970s before declining to an estimate 5.32 babies in 2019. This figure is higher than most world regions including South East Asia, Middle East and North Africa, Europe and Central Asia and America. The under-5-mortality-rate for Uganda has decreased from 191 deaths per 1000 live births in 1970 to 45.8 deaths per 1000 live births in 2019.

Diseases of poverty, also known as poverty-related diseases, are diseases that are more prevalent in low-income populations. They include infectious diseases, as well as diseases related to malnutrition and poor health behaviour. Poverty is one of the major social determinants of health. The World Health Report (2002) states that diseases of poverty account for 45% of the disease burden in the countries with high poverty rate which are preventable or treatable with existing interventions. Diseases of poverty are often co-morbid and ubiquitous with malnutrition. Poverty increases the chances of having these diseases as the deprivation of shelter, safe drinking water, nutritious food, sanitation, and access to health services contributes towards poor health behaviour. At the same time, these diseases act as a barrier for economic growth to affected people and families caring for them which in turn results into increased poverty in the community. These diseases produced in part by poverty are in contrast to diseases of affluence, which are diseases thought to be a result of increasing wealth in a society.

Available healthcare and health status in Sierra Leone is rated very poorly. Globally, infant and maternal mortality rates remain among the highest. The major causes of illness within the country are preventable with modern technology and medical advances. Most deaths within the country are attributed to nutritional deficiencies, lack of access to clean water, pneumonia, diarrheal diseases, anemia, malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS.

Mali, one of the world's poorest nations, is greatly affected by poverty, malnutrition, epidemics, and inadequate hygiene and sanitation. Mali's health and development indicators rank among the worst in the world, with little improvement over the last 20 years. Progress is impeded by Mali's poverty and by a lack of physicians. The 2012 conflict in northern Mali exacerbated difficulties in delivering health services to refugees living in the north. With a landlocked, agricultural-based economy, Mali is highly vulnerable to climate change. A catastrophic harvest in 2023 together with escalations in armed conflict have exacerbated food insecurity in Northern and Central Mali.

In terms of major health indicators, health in Paraguay ranks near the median among South American countries. In 2003 Paraguay had a child mortality rate of 29.5 deaths per 1,000 children, ranking it behind Argentina, Colombia, and Uruguay but ahead of Brazil and Bolivia. The health of Paraguayans living outside urban areas is generally worse than those residing in cities. Many preventable diseases, such as Chagas' disease, run rampant in rural regions. Parasitic and respiratory diseases, which could be controlled with proper medical treatment, drag down Paraguay's overall health. In general, malnutrition, lack of proper health care, and poor sanitation are the root of many health problems in Paraguay.

Healthcare in Laos is provided by both the private and public sector. It is limited in comparison with other countries. Western medical care is available in some locations, but remote areas and ethnic groups are underserved. Public spending on healthcare is low compared with neighbouring countries. Still, progress has been made since Laos joined the World Health Organization in 1950: life expectancy at birth rose to 66 years by 2015; malaria deaths and tuberculosis prevalence have plunged; and the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) has declined by 75 percent.

HIV/AIDS in Eswatini was first reported in 1986 but has since reached epidemic proportions. As of 2016, Eswatini had the highest prevalence of HIV among adults aged 15 to 49 in the world (27.2%).

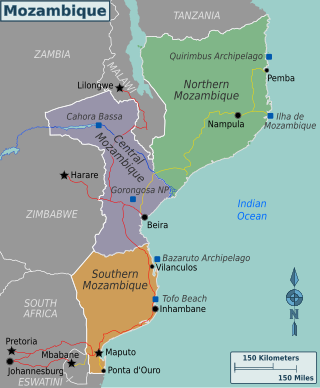

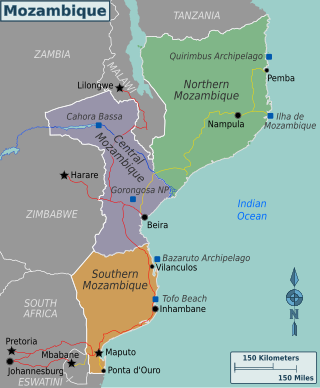

Mozambique is a country particularly hard-hit by the HIV/AIDS epidemic. According to 2008 UNAIDS estimates, this southeast African nation has the 8th highest HIV rate in the world. With 1,600,000 Mozambicans living with HIV, 990,000 of which are women and children, Mozambique's government realizes that much work must be done to eradicate this infectious disease. To reduce HIV/AIDS within the country, Mozambique has partnered with numerous global organizations to provide its citizens with augmented access to antiretroviral therapy and prevention techniques, such as condom use. A surge toward the treatment and prevention of HIV/AIDS in women and children has additionally aided in Mozambique's aim to fulfill its Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Nevertheless, HIV/AIDS has made a drastic impact on Mozambique; individual risk behaviors are still greatly influenced by social norms, and much still needs to be done to address the epidemic and provide care and treatment to those in need.

HIV/AIDS in Namibia is a critical public health issue. HIV has been the leading cause of death in Namibia since 1996, but its prevalence has dropped by over 70 percent in the years from 2006 to 2015. While the disease has declined in prevalence, Namibia still has some of the highest rates of HIV of any country in the world. In 2016, 13.8 percent of the adult population between the ages of 15 and 49 are infected with HIV. Namibia had been able to recover slightly from the peak of the AIDS epidemic in 2002. At the heart of the epidemic, AIDS caused the country's live expectancy to decline from 61 years in 1991 to 49 years in 2001. Since then, the life expectancy has rebounded with men living an average of 60 years and women living an average of 69 years

UNAIDS has said that HIV/AIDS in Indonesia is one of Asia's fastest growing epidemics. In 2010, it is expected that 5 million Indonesians will have HIV/AIDS. In 2007, Indonesia was ranked 99th in the world by prevalence rate, but because of low understanding of the symptoms of the disease and high social stigma attached to it, only 5-10% of HIV/AIDS sufferers actually get diagnosed and treated. According to the a census conducted in 2019, it is counted that 640,443 people in the country are living with HIV. The adult prevalence for HIV/ AIDS in the country is 0.4%. Indonesia is the country in Southeast Asia to have the most number of recorded people living with HIV while Thailand has the highest adult prevalence.

With less than 1 percent of the population estimated to be HIV-positive, Egypt is a low-HIV-prevalence country. However, between the years 2006 and 2011, HIV prevalence rates in Egypt increased tenfold. Until 2011, the average number of new cases of HIV in Egypt was 400 per year, but in 2012 and 2013, it increased to about 600 new cases, and in 2014, it reached 880 new cases per year. According to 2016 statistics from UNAIDS, there are about 11,000 people currently living with HIV in Egypt. The Ministry of Health and Population reported in 2020 over 13,000 Egyptians are living with HIV/AIDS. However, unsafe behaviors among most-at-risk populations and limited condom usage among the general population place Egypt at risk of a broader epidemic.

In precolonial Ghana, infectious diseases were the main cause of morbidity and mortality. The modern history of health in Ghana was heavily influenced by international actors such as Christian missionaries, European colonists, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund. In addition, the democratic shift in Ghana spurred healthcare reforms in an attempt to address the presence of infectious and noncommunicable diseases eventually resulting in the formation of the National Health insurance Scheme in place today.

The quality of health in Cambodia is rising along with its growing economy. The public health care system has a high priority from the Cambodian government and with international help and assistance, Cambodia has seen some major and continuous improvements in the health profile of its population since the 1980s, with a steadily rising life expectancy.

Health problems have been a long-standing issue limiting development in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The current population of Myanmar is 54.05 million. It was 27.27 million in 1970. The general state of healthcare in Myanmar is poor. The military government of 1962-2011 spent anywhere from 0.5% to 3% of the country's GDP on healthcare. Healthcare in Myanmar is consistently ranked among the lowest in the world. In 2015, in congruence with a new democratic government, a series of healthcare reforms were enacted. In 2017, the reformed government spent 5.2% of GDP on healthcare expenditures. Health indicators have begun to improve as spending continues to increase. Patients continue to pay the majority of healthcare costs out of pocket. Although, out of pocket costs were reduced from 85% to 62% from 2014 to 2015. They continue to drop annually. The global average of healthcare costs paid out of pocket is 32%. Both public and private hospitals are understaffed due to a national shortage of doctors and nurses. Public hospitals lack many of the basic facilities and equipment. WHO consistently ranks Myanmar among the worst nations in healthcare.

A landlocked sub-Saharan country, Burkina Faso is among the poorest countries in the world—44 percent of its population lives below the international poverty line of US$1.90 per day —and it ranks 185th out of 188 countries on UNDP's 2016 Human Development Index. Rapid population growth, gender inequality, and low levels of educational attainment contribute to food insecurity and poverty in Burkina Faso. The total population is just over 20 million with the estimated population growth rate is 3.1 percent per year and seven out of 10 Burkinabe are younger than 30. Total health care expenditures were an estimated 5% of GDP. Total expenditure on health per capita is 82 in 2014.

The health status of Namibia has increased steadily since independence, and the government does have focus on health in the country and seeks to make health service upgrades. As a guidance to achieve this goal, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) and World Health Organization (WHO) recently published the report "Namibia: State of the Nation's Health: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease." The report backs the fact that Namibia has made steady progress in the last decades when it comes to general health and communicable diseases, but despite this progress, HIV/AIDS still is the major reason for low life expectancy in the country.

Guinea faces a number of ongoing health challenges.

The quality of health in Rwanda has historically been very low, both before and immediately after the 1994 genocide. In 1998, more than one in five children died before their fifth birthday, often from malaria. But in recent years Rwanda has seen improvement on a number of key health indicators. Between 2005 and 2013, life expectancy increased from 55.2 to 64.0, under-5 mortality decreased from 106.4 to 52.0 per 1,000 live births, and incidence of tuberculosis has dropped from 101 to 69 per 100,000 people. The country's progress in healthcare has been cited by the international media and charities. The Atlantic devoted an article to "Rwanda's Historic Health Recovery". Partners In Health described the health gains "among the most dramatic the world has seen in the last 50 years".