Life

Power matriculated as a pensioner of Christ's College, Cambridge, in 1641 and graduated a Bachelor of Arts in 1644. [1] He became a regular correspondent of Sir Thomas Browne, who had lived in Halifax from 1633 to 1635 on scientific subjects. He graduated a Master of Arts in 1648 and a Doctor of Medicine in c. 1655. It appears that he practised his profession at Halifax for some time, but he eventually moved to New Hall, near Elland. Power was elected and admitted a fellow of the Royal Society 1 July 1663, he and Sir Justinian Isham, 2nd Baronet, being the first elected members.

He died at New Hall on 23 December 1668 and was buried in the All Saints' Church, Wakefield, with a brass plate to his memory, with a Latin inscription, on the floor in the middle chancel. [2]

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of modern science during the early modern period, when developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology and chemistry transformed the views of society about nature. The Scientific Revolution took place in Europe in the second half of the Renaissance period, with the 1543 Nicolaus Copernicus publication De revolutionibus orbium coelestium often cited as its beginning.

Robert Boyle was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the founders of modern chemistry, and one of the pioneers of modern experimental scientific method. He is best known for Boyle's law, which describes the inversely proportional relationship between the absolute pressure and volume of a gas, if the temperature is kept constant within a closed system. Among his works, The Sceptical Chymist is seen as a cornerstone book in the field of chemistry. He was a devout and pious Anglican and is noted for his writings in theology.

Boyle's law, also referred to as the Boyle–Mariotte law or Mariotte's law, is an empirical gas law that describes the relationship between pressure and volume of a confined gas. Boyle's law has been stated as:

The absolute pressure exerted by a given mass of an ideal gas is inversely proportional to the volume it occupies if the temperature and amount of gas remain unchanged within a closed system.

Henry Cavendish was an English natural philosopher and scientist who was an important experimental and theoretical chemist and physicist. He is noted for his discovery of hydrogen, which he termed "inflammable air". He described the density of inflammable air, which formed water on combustion, in a 1766 paper, On Factitious Airs. Antoine Lavoisier later reproduced Cavendish's experiment and gave the element its name.

John Wilkins was an Anglican clergyman, natural philosopher, and author, and was one of the founders of the Royal Society. He was Bishop of Chester from 1668 until his death.

Joseph Glanvill was an English writer, philosopher, and clergyman. Not himself a scientist, he has been called "the most skillful apologist of the virtuosi", or in other words the leading propagandist for the approach of the English natural philosophers of the later 17th century. In 1661 he predicted "To converse at the distance of the Indes by means of sympathetic conveyances may be as natural to future times as to us is a literary correspondence."

William Henry was an English chemist. He was the son of Thomas Henry and was born in Manchester England. He developed what is known today as Henry's Law.

Invisible College is the term used for a small community of interacting scholars who often met face-to-face, exchanged ideas and encouraged each other. One group that has been described as a precursor group to the Royal Society of London consisted of a number of natural philosophers around Robert Boyle, such as Christopher Wren. It has been suggested that other members included prominent figures later closely concerned with the Royal Society; but several groups preceded the formation of the Royal Society, and who the other members of this one were is still debated by scholars.

In the history of chemistry, the chemical revolution, also called the first chemical revolution, was the reformulation of chemistry during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, which culminated in the law of conservation of mass and the oxygen theory of combustion.

Corpuscularianism, also known as corpuscularism, is a set of theories that explain natural transformations as a result of the interaction of particles. It differs from atomism in that corpuscles are usually endowed with a property of their own and are further divisible, while atoms are neither. Although often associated with the emergence of early modern mechanical philosophy, and especially with the names of Thomas Hobbes, René Descartes, Pierre Gassendi, Robert Boyle, Isaac Newton, and John Locke, corpuscularian theories can be found throughout the history of Western philosophy.

Allen George Debus was an American historian of science, known primarily for his work on the history of chemistry and alchemy. In 1991 he was honored at the University of Chicago with an academic conference held in his name. Paul H. Theerman and Karen Hunger Parshall edited the proceedings, and Debus contributed his autobiography of which this article is a digest.

Robert Sharrock (1630–1684) was an English churchman and botanist. He is now known for The History of the Propagation and Improvement of Vegetables by the Concurrence of Art and Nature (1660), for philosophical work directed against Thomas Hobbes, and as an associate of Robert Boyle

George Starkey (1628–1665) was a Colonial American alchemist, medical practitioner, and writer of numerous commentaries and chemical treatises that were widely circulated in Western Europe and influenced prominent men of science, including Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton. After relocating from New England to London, England, in 1650, Starkey began writing under the pseudonym Eirenaeus Philalethes. Starkey remained in England and continued his career in medicine and alchemy until his death in the Great Plague of London in 1665.

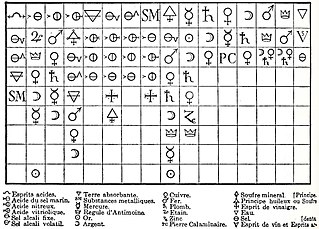

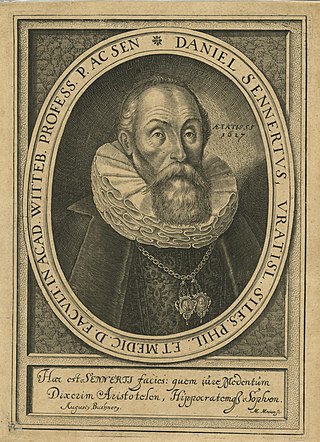

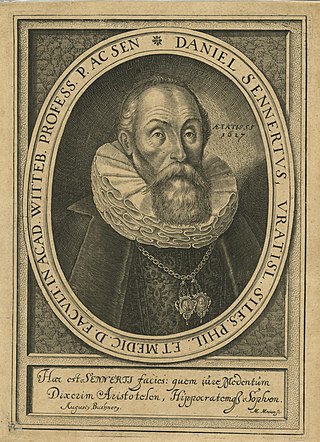

Daniel Sennert was a renowned German physician and a prolific academic writer, especially in the field of alchemy or chemistry. He held the position of professor of medicine at the University of Wittenberg for many years.

Richard Towneley was an English mathematician, natural philosopher and astronomer, resident at Towneley Hall, near Burnley in Lancashire. His uncle was the antiquarian and mathematician Christopher Towneley (1604–1674).

Marie Boas Hall was an American historian of science and is considered one of the postwar period pioneers of the study of the Scientific Revolution during the 16th and 17th centuries.

John Webster (1610–1682), also known as Johannes Hyphastes, was an English cleric, physician and chemist with occult interests, a proponent of astrology and a sceptic about witchcraft. He is known for controversial works.

John Beale was an English clergyman, scientific writer, and early Fellow of the Royal Society. He contributed to John Evelyn's Sylva, or A Discourse of Forest-Trees and the Propagation of Timber, and was an influential author on orchards and cider. He was also a member of the Hartlib Circle.

Peter Shaw (1694–1763) was an English physician and medical author.

John Young was an English stage actor of the seventeenth century. He was active as a member of the Duke's Company during the Restoration Era, appearing at Lincoln's Inn Fields and then at the Dorset Garden Theatre when the company relocated. While not much is known about his background, he was repeatedly in debt during his acting career. In 1667 he stood in for Thomas Betterton after he fell ill during the run of Macbeth appearing as the title role. Samuel Pepys described him as "a bad actor at best".

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : "Power, Henry". Dictionary of National Biography . London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : "Power, Henry". Dictionary of National Biography . London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.