Related Research Articles

Montana is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbia, and Saskatchewan to the north. It is the fourth-largest state by area, the eighth-least populous state, and the third-least densely populated state. Its state capital is Helena. The western half of Montana contains numerous mountain ranges, while the eastern half is characterized by western prairie terrain and badlands, with smaller mountain ranges found throughout the state.

Great Falls is the third most populous city in the U.S. state of Montana and the county seat of Cascade County. The population was 60,442 according to the 2020 census. The city covers an area of 22.9 square miles (59 km2) and is the principal city of the Great Falls, Montana, Metropolitan Statistical Area, which encompasses all of Cascade County. The Great Falls MSA’s population stood at 84,414 in the 2020 census.

The Chippewa Cree Tribe is a federally recognized tribe on the Rocky Boy Reservation in Montana who are descendants of Cree who migrated south from Canada and Chippewa (Ojibwe) who moved west from the Turtle Mountains in North Dakota in the late nineteenth century. The two different peoples spoke related but distinct Algonquian languages.

Fort Assinniboine was a United States Army fort located in present-day north central Montana. It was built in 1879 and operated by the Army through 1911. The 10th Cavalry Buffalo Soldiers, made up of African-American soldiers, were among the units making up the garrison at the fort. Determining that this fort was no longer needed after the end of the Indian Wars, the US Army closed and abandoned it.

Rocky Boy's Indian Reservation is one of seven Native American reservations in the U.S. state of Montana. Established by an act of Congress on September 7, 1916, it was named after Ahsiniiwin, the chief of the Chippewa band, who had died a few months earlier. It was established for landless Chippewa (Ojibwe) Indians in the American West, but within a short period of time many Cree (Nēhiyaw) and Métis were also settled there. Today the Cree outnumber the Chippewa on the reservation. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) recognizes it as the Chippewa Cree Reservation.

The Great Falls of the Missouri River are a series of waterfalls on the upper Missouri River in north-central Montana in the United States. From upstream to downstream, the five falls along a 10-mile (16 km) segment of the river are:

Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians of Montana is a federally-recognized tribe of Ojibwe people in Montana.

Fort Shaw was a United States Army fort located on the Sun River 24 miles west of Great Falls, Montana, in the United States. It was founded on June 30, 1867, and abandoned by the Army in July 1891. It later served as a school for Native American children from 1892 to 1910. Portions of the fort survive today as a small museum. The fort lent its name to the community of Fort Shaw, Montana, which grew up around it.

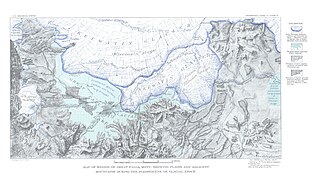

Lake Great Falls was a prehistoric proglacial lake which existed in what is now central Montana in the United States between 15,000 BCE and 11,000 BCE. Centered on the modern city of Great Falls, Montana, Glacial Lake Great Falls extended as far north as Cut Bank, Montana, and as far south as Holter Lake. At present-day Great Falls, the Glacial Lake Great Falls reached a depth of 600 feet.

The Shonkin Sag is a prehistoric fluvioglacial landform located along the northern edge of the Highwood Mountains in the state of Montana in the United States. The Sag is a river channel formed by the Missouri River and glacial meltwater pouring from Glacial Lake Great Falls. It is one of the most famous prehistoric meltwater channels in the world.

The Pryor Mountains are a mountain range in Carbon and Big Horn counties of Montana, and Big Horn County, Wyoming. They are located on the Crow Indian Reservation and the Custer National Forest, and portions of them are on private land. They lie south of Billings, Montana, and north of Lovell, Wyoming.

Medicine Rocks State Park is a park owned by the state of Montana in the United States. It is located about 25 miles (40 km) west-southwest of Baker, Montana, and 11 miles (18 km) north of Ekalaka, Montana. The park is named for the "Medicine Rocks," a series of sandstone pillars similar to hoodoos some 60 to 80 feet high with eerie undulations, holes, and tunnels in them. The rocks contain numerous examples of Native American rock art and are considered a sacred place by Plains Indians. As a young rancher, future president Theodore Roosevelt said Medicine Rocks was "as fantastically beautiful a place as I have ever seen." The park is 330 acres (130 ha) in size, sits at 3,379 feet (1,030 m) in elevation, and is managed by the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2017 and designated as a certified International Dark Sky Sanctuary in 2020.

The following works deal with the cultural, political, economic, military, biographical and geologic history of pre-territorial Montana, Montana Territory and the State of Montana.

Black Eagle Dam is a hydroelectric gravity weir dam located on the Missouri River in the city of Great Falls, Montana. The first dam on the site, built and opened in 1890, was a timber-and-rock crib dam. This structure was the first hydroelectric dam built in Montana and the first built on the Missouri River. The dam helped give the city of Great Falls the nickname "The Electric City." A second dam, built of concrete in 1926 and opened in 1927, replaced the first dam, which was not removed and lies submerged in the reservoir. Almost unchanged since 1926, the dam is 782 feet (238 m) long and 34.5 feet (10.5 m) high, and its powerhouse contains three turbines capable of generating seven megawatts (MW) of power each. The maximum power output of the dam is 18 MW. Montana Power Company built the second dam, PPL Corporation purchased it in 1997 and sold it to NorthWestern Corporation in 2014. The reservoir behind the dam has no official name, but was called the Long Pool for many years. The reservoir is about 2 miles (3.2 km) long, and has a storage capacity of 1,710 acre-feet (2,110,000 m3) to 1,820 acre-feet (2,240,000 m3) of water.

First Peoples Buffalo Jump State Park is a Montana state park and National Historic Landmark in Cascade County, Montana in the United States. The park is 1,481 acres (599 ha) and sits at an elevation of 3,773 feet (1,150 m). It is located about 3.5 miles (5.6 km) northwest of the small town of Ulm, which is near the city of Great Falls. First Peoples Buffalo Jump State Park contains the Ulm Pishkun, a historic buffalo jump utilized by the Native American tribes of North America. It has been described as, geographically speaking, either North America's largest buffalo jump or the world's largest. There is some evidence that it was the most utilized buffalo jump in the world. The site was added to the National Register of Historic Places on December 17, 1974, and designated a National Historic Landmark in August 2015. The former name of the park was derived from the Blackfeet word "Pis'kun," meaning "deep kettle of blood," and the nearby town of Ulm.

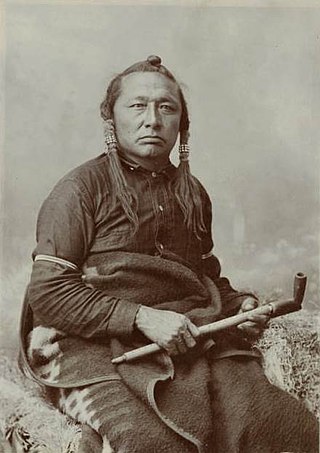

Asiniiwin, translated Rocky Boy or Stone Child, was an important Chippewa leader who was chief of a band in Montana in the late 19th century and early 20th century. His advocacy for his people helped gain the establishment of what is called Rocky Boy's Indian Reservation in his honor. Formed from part of Fort Assiniboine, which was closed, it is located in Hill and Chouteau counties in north central Montana.

Little Bear was a Cree leader who lived in the District of Alberta, Idaho Territory, Montana Territory, and District of Saskatchewan regions of Canada and the United States, in the 19th and early 20th centuries. He is known for his participation in the 1885 North-West Rebellion, which was fought in Alberta and Saskatchewan.

The Thermopolis Shale is a geologic formation which formed in west-central North America in the Albian age of the Late Cretaceous period. Surface outcroppings occur in central Canada, and the U.S. states of Montana and Wyoming. The rock formation was laid down over about 7 million years by sediment flowing into the Western Interior Seaway. The formation's boundaries and members are not well-defined by geologists, which has led to different definitions of the formation. Some geologists conclude the formation should not have a designation independent of the formations above and below it. A range of invertebrate and small and large vertebrate fossils and coprolites are found in the formation.

Tower Rock State Park is a state park near the community of Cascade in the U.S. state of Montana in the United States. The centerpiece of the park is Tower Rock, a 424-foot (129 m)-high rock formation which marks the entrance to the Missouri River Canyon in the Adel Mountains Volcanic Field. It was well known to Native Americans, and considered a sacred place by the Piegan Blackfeet. Tower Rock received its current name when Meriwether Lewis of the Lewis and Clark Expedition visited the site in 1805. Railroad and highway development in the late 1800s and 1900s skirted Tower Rock, but the landform itself remained pristine. The 87.2 acres (0.353 km2) encompassing Tower Rock was added to the National Register of Historic Places on March 18, 2002. The 140-acre (0.57 km2) Tower Rock State Park was created around the National Historic Site in 2004.

Marjorie Bear Don't Walk is an Ojibwa-Salish health care professional and Native American fashion designer. She is most known as an advocate for reforms in the Indian Health Service, and specifically the care of urban Native Americans. In addition, she is a fashion designer who has targeted career women, designing professional attire which incorporated traditional techniques into her clothing.

References

- Notes

- ↑ This gravel is derived from Belt Series rock, [7] a Precambrian metasedimentary rock. [15]

- ↑ Landless Native Americans living near the meatpacking plant had long found occasional work there. [29]

- Citations

- ↑ Malone, Roeder & Lang 1991, p. 21.

- ↑ Sonneborn 2007, p. 287.

- 1 2 Montana Almanac 1958, p. 117.

- 1 2 3 Robison 2011, p. 79.

- 1 2 Eder 1983, p. 32.

- ↑ Proctor, Cody; Sherman, David (June 10, 2015). "Firefighters offer tips to protect against wildfires in Great Falls communities". KXLH-TV. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Hansen 2000, p. 60.

- 1 2 Leckie, D.A.; Bhattacharya, J.P.; Bloch, J.; Gilboy, C.F.; Norris, B. (1994). "Chapter 20 - Cretaceous Colorado/Alberta Group of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin. Geological Atlas of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin". Alberta Geological Survey. Archived from the original on October 24, 2010. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ↑ Keroher 1966, p. 367.

- ↑ Keroher 1966, p. 1376.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lewis 1959, p. 148.

- ↑ Alden 1932, pp. vii–viii, 14, 49.

- ↑ Clawson & Shandera 1998, p. 13.

- ↑ Alden 1932, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Keroher 1966, pp. 294–295.

- ↑ Hill & Valppu 1997, pp. 159–161.

- ↑ Feathers, James K.; Hill, Christopher L. (2003). Luminescence Dating of Glacial Lake Great Falls, Montana, U.S.A. Stratigraphy and Geochronology Session. XVI International Quaternary Association Congress (Report). Reno, Nev.: International Quaternary Association. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- 1 2 Robison 2015, p. 373.

- 1 2 3 Pomnichowski, Ralph (June 28, 2009). "1920 to 1929: The Roaring Decade Was Hard on Montana and the Electric City". Great Falls Tribune. p. Anniversary Section, p. 7. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Peterson 2010, p. 123.

- ↑ Thompson, Ellen (March–April 2006). "Off the Res". Legal Affairs. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ↑ Henry 1950, p. 176.

- ↑ Subcommittees of the Committees on Interior and Insular Affairs 1954, p. 895.

- ↑ Gallant 2012, p. 54.

- 1 2 3 Basso 2013, p. 63.

- ↑ Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs 1969, p. 5573.

- ↑ Wilmot, Paula (April 4, 2010). "Test What You Know of Area's Rich History During 1920s". Great Falls Tribune.

- ↑ Cates, Kristen (July 3, 2012). "Great Falls High Students Paint GF Landmark on Hill 57". Great Falls Tribune.

- 1 2 3 Basso 2013, p. 58.

- ↑ Bureau of Land Management 1960, p. 52.

- 1 2 Basso 2013, p. 59.

- ↑ Basso 2013, pp. 57–58.

- ↑ Malone 2006, p. 68.

- ↑ Basso 2013, p. 57.

- ↑ Basso 2013, p. 60.

- ↑ Basso 2013, p. 64.

- 1 2 Barnhill 2013, p. 219.

- ↑ Campbell, Justin (October 26, 2014). "Little Shell Chippewa Tribe Holds Wellness Camp". KFBB-TV. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ↑ Wilson 1998, pp. 49–51.