Veterinary medicine is the branch of medicine that deals with the prevention, management, diagnosis, and treatment of disease, disorder, and injury in animals. Along with this, it deals with animal rearing, husbandry, breeding, research on nutrition, and product development. The scope of veterinary medicine is wide, covering all animal species, both domesticated and wild, with a wide range of conditions that can affect different species.

A veterinarian (vet), also known as a veterinary surgeon or veterinary physician, is a medical professional who practices veterinary medicine. They manage a wide range of health conditions and injuries in non-human animals. Along with this, vets also play a role in animal reproduction, animal health management, conservation, husbandry and breeding and preventive medicine like animal nutrition, vaccination and parasitic control as well as biosecurity and zoonotic disease surveillance and prevention.

The Virginia–Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine is a state-supported college of two states, Virginia and Maryland, filling the need for veterinary medicine education in both states. Students from both states are considered "in-state" students for admissions purposes.

A veterinary specialist is a veterinarian who specializes in a clinical field of veterinary medicine.

The U.S. Army Veterinary Corps is a staff corps of the U.S. Army Medical Department (AMEDD) consisting of commissioned veterinary officers and Health Professions Scholarship Program (HPSP) veterinary students. It was established by an Act of Congress on 3 June 1916. Recognition of the need for veterinary expertise had been evolving since 1776 when General Washington directed that a "regiment of horse with a farrier" be raised. It has evolved to include sanitary food inspectors and animal healthcare specialists.

Veterinary education is the tertiary education of veterinarians. To become a veterinarian, one must first complete a veterinary degree in Doctor of Veterinary Medicine.

The Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, commonly referred to as the Dick Vet, is the veterinary school of the University of Edinburgh in Scotland and part of the College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine the head of which is Moira Whyte. David Argyle has been Dean and Head of School since 1 November 2011.

North Carolina State University College of Veterinary Medicine is an American educational institution located in Raleigh, North Carolina that offers master's and doctorate-level degree programs; interdisciplinary research in a range of veterinary and comparative medicine topics through centers, institutes, programs and laboratories; and external engagement through public service programs and activities.

Veterinary acupuncture is a form of traditional Chinese medicine and a pseudoscientific practice of performing acupuncture on animals. The best studies of the effects of animal acupuncture have produced consistently negative results.

In horse trading, an equine prepurchase exam is an examination of a horse requested by the buying party prior to the purchase, in order to identify any preexisting problems which may affect a horse's future performance and reduce buyer risk. The inspection usually consists of four phases in which a veterinarian examines all aspects of the horse's health.

Veterinary chiropractic, also known as animal chiropractic, is the practice of spinal manipulation or manual therapy for animals. Veterinary chiropractors typically treat horses, racing greyhounds, and pets. Veterinary chiropractic is a fast-developing field that is complementary to the conventional approach.

The Faculty of Veterinary Science is a faculty of the University of Pretoria. Founded in 1920, it is the second oldest veterinary faculty in Africa. With the exception of the faculties in Khartoum, and Cairo, all the other African faculties were established after 1960. It is the only one of its kind in South Africa and is one of 33 veterinary faculties in Africa.

Paraveterinary worker is the professional of veterinary science that performs procedures autonomously or semi autonomously, as part of a veterinary assistance system. The job role varies throughout the world, and common titles include veterinary nurse, veterinary technician and veterinary assistant, and variants with the prefix of 'animal health'.

Veterinary medicine in the United Kingdom is the performance of veterinary medicine by licensed professionals. It is strictly regulated by the statute law, notably the Veterinary Surgeons Act 1966. Veterinary medicine is led by veterinary physicians, termed "veterinary surgeons", normally referred to as "vets".

Veterinary medicine in the United States is the performance of veterinary medicine in the United States, normally performed by licensed professionals, and subject to provisions of statute law which vary by state. Veterinary medicine is normally led by veterinary physicians, termed veterinarians or vets.

The history of veterinary medicine in the Philippines discusses the history of veterinary medicine as a profession in the Philippines. Its history in the Philippines began in 1828, while the Philippines was still a colony of Spain, progressing further during the time when the Philippines became a territory of the United States, until the establishment of the Philippines as an independent Republic in the modern-day era.

Zoobiquity is a 2012 non-fiction science book co-written by the cardiologist Barbara Natterson-Horowitz and Kathryn Bowers. It was a New York Times Bestseller.

Susan Marie Stover is a professor of veterinary anatomy at the University of California, Davis School of Veterinary Medicine and director of the J.D. Wheat Veterinary Orthopedic Research Laboratory. One of the focuses of her wide-ranging research is musculoskeletal injuries in racehorses, particularly catastrophic breakdowns. Her identification of risk factors has resulted in improved early detection and changes to horse training and surgical repair methods. On July 30, 2016, Stover received the Lifetime Excellence in Research Award from the American Veterinary Medical Association. In August 2016, she was selected for induction into the University of Kentucky Equine Research Hall of Fame.

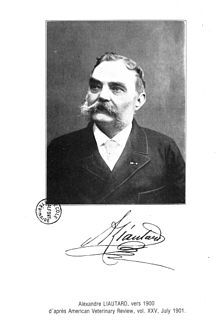

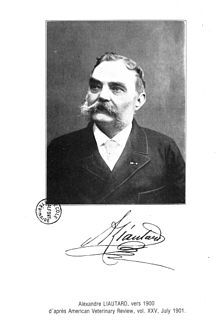

Alexandre François Augustin Liautard was a French veterinarian. After graduating from the École nationale vétérinaire de Toulouse in 1856, he emigrated to the United States in 1859 to exercise his profession of veterinary practitioner in New York until 1900, when he retired and returned to France. The name of Alexandre Liautard is associated with the beginning of private veterinary education in America. Liautard was the founder and dean of the New York American Veterinary College. He participated in organizing the American Veterinary profession and founded the United States Veterinary Medical Association, now the American Veterinary Medical Association, of which he was for many years a driving force. His name is still cited in the American veterinary press as a dominant figure in the history of the profession for having defined its professional standards and missions, and been a uniting force, and as founder of the American Veterinary Review, now the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association (JAVMA).