In corporate finance, a debenture is a medium- to long-term debt instrument used by large companies to borrow money, at a fixed rate of interest. The legal term "debenture" originally referred to a document that either creates a debt or acknowledges it, but in some countries the term is now used interchangeably with bond, loan stock or note. A debenture is thus like a certificate of loan or a loan bond evidencing the company's liability to pay a specified amount with interest. Although the money raised by the debentures becomes a part of the company's capital structure, it does not become share capital. Senior debentures get paid before subordinate debentures, and there are varying rates of risk and payoff for these categories.

Debt restructuring is a process that allows a private or public company or a sovereign entity facing cash flow problems and financial distress to reduce and renegotiate its delinquent debts to improve or restore liquidity so that it can continue its operations.

Distressed securities are securities over companies or government entities that are experiencing financial or operational distress, default, or are under bankruptcy. As far as debt securities, this is called distressed debt. Purchasing or holding such distressed-debt creates significant risk due to the possibility that bankruptcy may render such securities worthless.

A vulture fund is a hedge fund, private-equity fund or distressed debt fund, that invests in debt considered to be very weak or in default, known as distressed securities. Investors in the fund profit by buying debt at a discounted price on a secondary market and then using numerous methods to subsequently sell the debt for a larger amount than the purchasing price. Debtors include companies, countries, and individuals.

The Argentine debt restructuring is a process of debt restructuring by Argentina that began on January 14, 2005, and allowed it to resume payment on 76% of the US$82 billion in sovereign bonds that defaulted in 2001 at the depth of the worst economic crisis in the nation's history. A second debt restructuring in 2010 brought the percentage of bonds under some form of repayment to 93%, though ongoing disputes with holdouts remained. Bondholders who participated in the restructuring settled for repayments of around 30% of face value and deferred payment terms, and began to be paid punctually; the value of their nearly worthless bonds also began to rise. The remaining 7% of bondholders were later repaid 25% less than they were demanding, after centre-right and US-aligned leader Mauricio Macri came to power in 2015.

A collective action clause (CAC) allows a supermajority of bondholders to agree to a debt restructuring that is legally binding on all holders of the bond, including those who vote against the restructuring. Bondholders generally opposed such clauses in the 1980s and 1990s, fearing that it gave debtors too much power. However, following Argentina's December 2001 default on its debts in which its bonds lost 70% of their value, CACs have become much more common, as they are now seen as potentially warding off more drastic action, but enabling easier coordination of bondholders.

Exit consent is a formal agreement that allows a majority group of creditors holding sovereign bonds to change the non-financial terms of the bonds in a way that makes the bonds effectively worthless for the minority holdouts, motivating them to accept a restructuring offer. Thus creditors willing to restructure can outmaneuver holdouts by using the supermajority voting features of existing bonds to secure changes, which reduce their value as they are tendered in exchange for restructured debt.

David Martínez Guzmán is a Mexican investor who is the founder and managing partner of Fintech Advisory. This firm specializes in corporate and sovereign debt. Fintech Advisory has offices in London and New York City, and he currently divides his time between those two cities.

A sovereign default is the failure or refusal of the government of a sovereign state to pay back its debt in full when due. Cessation of due payments may either be accompanied by that government's formal declaration that it will not pay its debts (repudiation), or it may be unannounced. A credit rating agency will take into account in its gradings capital, interest, extraneous and procedural defaults, and failures to abide by the terms of bonds or other debt instruments.

The Corporation of Foreign Bondholders was a British association established in London in 1868 by private holders of debt securities issued by foreign governments, states and municipalities. In an era before extensive financial regulation.and of wide sovereign immunity, it provided a forum for British creditors to co-ordinate their actions during the financial boom from the 1860s to the 1950s. It created an important mechanism through which investors could formulate proposals to deal with the government defaults, particularly in the Great Depression following the 1929 Wall Street crash, including several early debt restructurings.

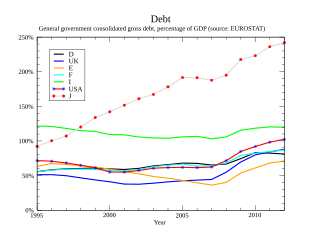

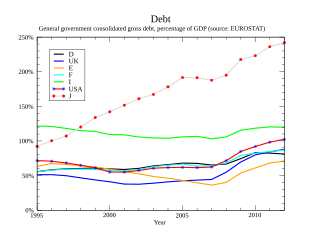

The European debt crisis, often also referred to as the eurozone crisis or the European sovereign debt crisis, was a multi-year debt crisis that took place in the European Union (EU) from 2009 until the mid to late 2010s. Several eurozone member states were unable to repay or refinance their government debt or to bail out over-indebted banks under their national supervision without the assistance of third parties like other eurozone countries, the European Central Bank (ECB), or the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Debt crisis is a situation in which a government loses the ability of paying back its governmental debt. When the expenditures of a government are more than its tax revenues for a prolonged period, the government may enter into a debt crisis. Various forms of governments finance their expenditures primarily by raising money through taxation. When tax revenues are insufficient, the government can make up the difference by issuing debt.

Hernán Gaspar Lorenzino is an Argentine lawyer and public policy maker. He was appointed Minister of Economy of Argentina by President Cristina Kirchner in 2011.

In the context of sovereign debt crisis, private sector involvement (PSI) refers, broadly speaking, to the forced contribution of private sector creditors to a financial crisis resolution process, and, specifically, to the private sector incurring outright reductions ("haircuts") on the value of its debt holdings.

Axel Kicillof is an Argentine Peronist economist and politician who has been Governor of Buenos Aires Province since 2019.

Jubilee USA Network is a nonprofit financial reform organization based in Washington D.C. Jubilee USA's work began in conjunction with the global Jubilee 2000 movement, founded in the late 1990s to advocate for debt relief for developing countries. It is "an alliance of more than 75 U.S. organizations, 650 faith communities and 50 Jubilee global partners."

The Second Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece, usually referred to as the second bailout package or the second memorandum, is a memorandum of understanding on financial assistance to the Hellenic Republic in order to cope with the Greek government-debt crisis.

Republic of Argentina v. NML Capital, Ltd., 573 U.S. 134 (2014), is a U.S. Supreme Court opinion regarding foreign sovereign immunity. After defaulting on its debt and losing a federal collection action, Argentina claimed that its foreign assets were immune from discovery. The Court found that no such immunity existed.

Greylock Capital Management, LLC is a U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission registered alternative investment adviser that invests in undervalued, distressed, and high yield assets worldwide, particularly in emerging and frontier markets. As is the case with comparable funds, the firm's investor base consists largely of institutional investors and a limited number of high net worth individuals. As a group, institutional investors may include banks, credit unions, insurance companies, pension funds, hedge funds, REITs, endowments and mutual funds. As is common with many asset management firms, Greylock Capital is organized across a series of onshore and offshore limited partnerships.