Wall Township is a township within Monmouth County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. Crisscrossed by several different highways within the heart of the Jersey Shore region, the township is a transportation hub of Central New Jersey and a bedroom suburb of New York City, in the New York Metropolitan Area. As of the 2020 United States census, Wall Township's population was 26,525, its highest decennial count ever and an increase of 361 (+1.4%) from the 2010 census count of 26,164, which in turn reflected an increase of 903 (+3.6%) from the 25,261 counted in the 2000 census.

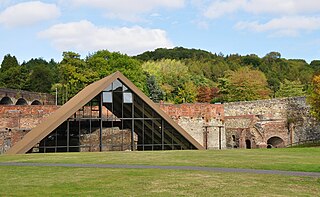

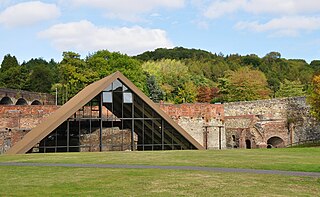

Coalbrookdale is a village in the Ironbridge Gorge and the Telford and Wrekin borough of Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. It lies within the civil parish called the Gorge.

Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site is a National Historic Site about 10 miles northeast of Downtown Boston in Saugus, Massachusetts. It is the site of the first integrated ironworks in North America, founded by John Winthrop the Younger and in operation between 1646 and approximately 1670. It includes the reconstructed blast furnace, forge, rolling mill, shear, slitter and a quarter-ton trip hammer.

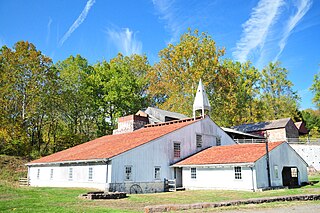

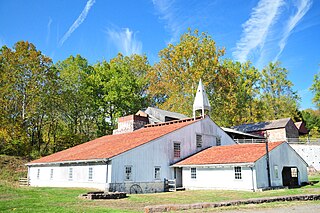

Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site in southeastern Berks County, near Elverson, Pennsylvania, is an example of an American 19th century rural iron plantation, whose operations were based around a charcoal-fired cold-blast iron blast furnace. The significant restored structures include the furnace group (blast furnace, water wheel, blast machinery, cast house and charcoal house), as well as the ironmaster's house, a company store, the blacksmith's shop, a barn and several worker's houses.

Arthur Brisbane was one of the best known American newspaper editors of the 20th century as well as a real estate investor.

Allaire State Park is a park located in Howell and in Wall Township in Monmouth County, New Jersey, United States, near the borough of Farmingdale, operated and maintained by the New Jersey Division of Parks and Forestry and is part of the New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail Route. The park is known for its restored 19th century ironworks, Allaire Village, on the park premises. It is named after James P. Allaire, founder of the Howell Works at the same site. The park also hosts the Pine Creek Railroad, a tourist railroad.

Iron plantations were rural localities emergent in the late-18th century and predominant in the early-19th century that specialized in the production of pig iron and bar iron from crude iron ore.

Allaire Village is a living history museum located within New Jersey's Allaire State Park in Wall Township, Monmouth County, New Jersey. The property was initially an Indian ceremonial ground prior to 1650, by 1750 a sawmill had been established on the property by Issac Palmer. The village was later established as a bog iron furnace originally known as Williamsburg Forge 'Monmouth Furnace' was then renamed the Howell Works by Benjamin B. Howell. In 1822, it was then purchased by philanthropist James P. Allaire, who endeavoured to turn into a self-contained community. The wood burning furnace business collapsed in 1846 and the village closed. During its height, the town supported about 500 people. Following his death, the property passed through a number of family members before being used by the Boy Scouts who started to restore the buildings for use as a summer camp. Losing the lease, the property then passed to the State of New Jersey. Allaire Village and its existing buildings are now operated by a non-profit organization - Allaire Village, Inc. Historic interpreters work using period tools and equipment in the blacksmith, tinsmith, and carpentry shops, while the old bakery sells cookies, and general store serves as a museum gift-shop styled store. The church building is frequently used for weddings. The site is also host to community events such as community band concerts, antique sales, weekly flea markets and square dance competitions.

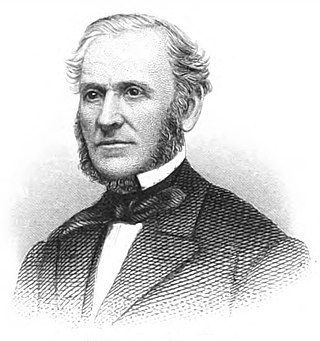

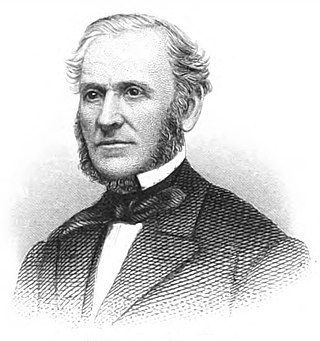

James Peter Allaire was a master mechanic and steam engine builder, and founder of the Allaire Iron Works, the first marine steam engine company in New York City, and later Howell Works, in Wall Township, New Jersey. His credits also include building both the first compound steam engine for marine use and the first New York City tenement structure.

The Freehold and Jamesburg Agricultural Railroad was a short-line railroad in New Jersey. The railroad traversed through the communities of Freehold Borough, Freehold Township, Manalapan Township, Englishtown Borough, Monroe Township, and Jamesburg Borough, en route to Monmouth Junction in South Brunswick Township.

Oxford Furnace is a historic blast furnace on Washington Avenue, near the intersection with Belvidere Avenue, in Oxford, Oxford Township, Warren County, New Jersey. The furnace was built by Jonathan Robeson in 1741 and produced its first pig iron in 1743. The first practical use in the United States of hot blast furnace technology took place here in 1834. The furnace was added to the National Register of Historic Places on July 6, 1977 for its significance in industry during the 19th century. It was later added as a contributing property to the Oxford Industrial Historic District on August 27, 1992.

Cornwall Iron Furnace is a designated National Historic Landmark that is administered by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission in Cornwall, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania in the United States. The furnace was a leading Pennsylvania iron producer from 1742 until it was shut down in 1883. The furnaces, support buildings and surrounding community have been preserved as a historical site and museum, providing a glimpse into Lebanon County's industrial past. The site is the only intact charcoal-burning iron blast furnace in its original plantation in the western hemisphere. Established by Peter Grubb in 1742, Cornwall Furnace was operated during the Revolution by his sons Curtis and Peter Jr. who were major arms providers to George Washington. Robert Coleman acquired Cornwall Furnace after the Revolution and became Pennsylvania's first millionaire. Ownership of the furnace and its surroundings was transferred to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1932.

John Roach was an American industrialist who rose from humble origins as an Irish immigrant laborer to found the largest and most productive shipbuilding empire in the Reconstruction Era United States, John Roach & Sons.

The Allaire Iron Works was a leading 19th-century American marine engineering company based in New York City. Founded in 1816 by engineer and philanthropist James P. Allaire, the Allaire Works was one of the world's first companies dedicated to the construction of marine steam engines, supplying the engines for more than 50% of all the early steamships built in the United States.

The Etna Iron Works was a 19th-century ironworks and manufacturing plant for marine steam engines located in New York City. The Etna Works was a failing small business when purchased by ironmolder John Roach and three partners in 1852. Roach soon gained full ownership of the business and quickly transformed it into a successful general-purpose ironworks.

The Delaware River Iron Ship Building and Engine Works was a major late-19th-century American shipyard located on the Delaware River in Chester, Pennsylvania. It was founded by the industrialist John Roach and is often referred to by its parent company name of John Roach & Sons, or just known as the Roach shipyard. For the first fifteen years of its existence, the shipyard was by far the largest and most productive in the United States, building more tonnage of ships than its next two major competitors combined, in addition to being the U.S. Navy's largest contractor. The yard specialized in the production of large passenger freighters, but built every kind of vessel from warships to cargo ships, oil tankers, ferries, barges, tugs and yachts.

The Grubb Family Iron Dynasty was a succession of iron manufacturing enterprises owned and operated by Grubb family members for more than 165 years. Collectively, they were Pennsylvania's leading iron manufacturer between 1840 and 1870.

Batsto Village is a historic unincorporated community located on CR 542 within Washington Township in Burlington County, New Jersey, United States. It is located in Wharton State Forest in the south central Pine Barrens, and a part of the Pinelands National Reserve. It is listed on the New Jersey and National Register of Historic Places, and is administered by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection's Division of Parks & Forestry. The name is derived from the Swedish bastu, bathing place ; the first bathers were probably the Lenni Lenape Native Americans.

Theodosius Fowler Secor was an American marine engineer. Secor co-founded T. F. Secor & Co. in New York in 1838, which was one of the leading American marine engineering facilities of its day. In 1850, he sold his stake in the company to his erstwhile partner, Charles Morgan, in order to go into partnership with Cornelius Vanderbilt in the purchase of another leading New York marine engineering facility, the Allaire Iron Works.

Martha Furnace is an abandoned iron furnace in Burlington County, New Jersey, in the New Jersey Pine Barrens. It operated between 1793 and the mid-1840s, using charcoal fuel and locally-mined bog iron to make a variety of cast products as well as pig iron. For most of its operating history, it was principally owned by the New Jersey ironmaster Samuel Richards and managed by Jesse Evans. The settlement that grew up around it was abandoned after ironmaking ceased, and the site of the furnace now lies undeveloped in Wharton State Forest.