The Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution is part of the Bill of Rights. It prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures. In addition, it sets requirements for issuing warrants: warrants must be issued by a judge or magistrate, justified by probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and must particularly describe the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized.

Telephone tapping is the monitoring of telephone and Internet-based conversations by a third party, often by covert means. The wire tap received its name because, historically, the monitoring connection was an actual electrical tap on the telephone line. Legal wiretapping by a government agency is also called lawful interception. Passive wiretapping monitors or records the traffic, while active wiretapping alters or otherwise affects it.

The Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 (ECPA) was enacted by the United States Congress to extend restrictions on government wire taps of telephone calls to include transmissions of electronic data by computer, added new provisions prohibiting access to stored electronic communications, i.e., the Stored Communications Act, and added so-called pen trap provisions that permit the tracing of telephone communications . ECPA was an amendment to Title III of the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968, which was primarily designed to prevent unauthorized government access to private electronic communications. The ECPA has been amended by the Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA) of 1994, the USA PATRIOT Act (2001), the USA PATRIOT reauthorization acts (2006), and the FISA Amendments Act (20

Mobile phone tracking is a process for identifying the location of a mobile phone, whether stationary or moving. Localization may be effected by a number of technologies, such as the multilateration of radio signals between (several) cell towers of the network and the phone or by simply using GNSS. To locate a mobile phone using multilateration of mobile radio signals, the phone must emit at least the idle signal to contact nearby antenna towers and does not require an active call. The Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM) is based on the phone's signal strength to nearby antenna masts.

Kyllo v. United States, 533 U.S. 27 (2001), held in a 5–4 decision which crossed ideological lines that the use of a thermal imaging, or FLIR, device from a public vantage point to monitor the radiation of heat from a person's home was a "search" within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment, and thus required a warrant.

The Stored Communications Act is a law that addresses voluntary and compelled disclosure of "stored wire and electronic communications and transactional records" held by third-party internet service providers (ISPs). It was enacted as Title II of the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 (ECPA).

United States v. Warshak, 631 F.3d 266 is a criminal case decided by the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit holding that government agents violated the defendant's Fourth Amendment rights by compelling his Internet service provider (ISP) to turn over his emails without first obtaining a search warrant based on probable cause. However, constitutional violation notwithstanding, the evidence obtained with these emails was admissible at trial because the government agents relied in good faith on the Stored Communications Act (SCA). The court further declared that the SCA is unconstitutional to the extent that it allows the government to obtain emails without a warrant.

United States v. Jones, 565 U.S. 400 (2012), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case which held that installing a Global Positioning System (GPS) tracking device on a vehicle and using the device to monitor the vehicle's movements constitutes a search under the Fourth Amendment.

The StingRay is an IMSI-catcher, a cellular phone surveillance device, manufactured by Harris Corporation. Initially developed for the military and intelligence community, the StingRay and similar Harris devices are in widespread use by local and state law enforcement agencies across Canada, the United States, and in the United Kingdom. Stingray has also become a generic name to describe these kinds of devices.

The Geolocation Privacy and Surveillance Act was a bill introduced in the U.S. Congress in 2011 that attempted to limit government surveillance using geolocation information such as signals from GPS systems in mobile devices. The bill was sponsored by Sen. Ron Wyden and Rep. Jason Chaffetz. Since its initial proposal in June 2011, the GPS Act awaits consideration by the Senate Judiciary Committee as well as the House.

United States v. Graham, 846 F. Supp. 2d 384, was a Maryland District Court case in which the Court held that historical cell site location data is not protected by the Fourth Amendment. Reacting to the precedent established by the recent Supreme Court case United States v. Jones in conjunction with the application of the third party doctrine, Judge Richard D. Bennett, found that "information voluntarily disclosed to a third party ceases to enjoy Fourth Amendment protection" because that information no longer belongs to the consumer, but rather to the telecommunications company that handles the transmissions records. The historical cell site location data is then not subject to the privacy protections afforded by the Fourth Amendment standard of probable cause, but rather to the Stored Communications Act, which governs the voluntary or compelled disclosure of stored electronic communications records.

The third-party doctrine is a United States legal doctrine that holds that people who voluntarily give information to third parties—such as banks, phone companies, internet service providers (ISPs), and e-mail servers—have "no reasonable expectation of privacy" in that information. A lack of privacy protection allows the United States government to obtain information from third parties without a legal warrant and without otherwise complying with the Fourth Amendment prohibition against search and seizure without probable cause and a judicial search warrant.

American Civil Liberties Union v. James Clapper, No. 13-3994, 959 F.Supp.2d 724, was a lawsuit by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and its affiliate, the New York Civil Liberties Union, against the United States federal government that challenged the legality of the National Security Agency's (NSA) bulk phone metadata collection program. On December 27, 2013, the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York dismissed the case, finding that the collection of metadata did not violate the Fourth Amendment. On January 2, 2014, the ACLU appealed the ruling to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. On May 7, 2015, the appeals court ruled that Section 215 of the Patriot Act did not authorize the bulk collection of metadata, which judge Gerard E. Lynch called a "staggering" amount of information.

Riley v. California, 573 U.S. 373 (2014), is a landmark United States Supreme Court case in which the Court unanimously held that the warrantless search and seizure of digital contents of a cell phone during an arrest is unconstitutional.

United States v. Quartavious Davis is a United States federal legal case that challenged the use in a criminal trial of location data obtained without a search warrant from MetroPCS, a cell phone service provider. Mobile phone tracking data had helped place the defendant in this case at the scene of several crimes, for which he was convicted. The defendant appealed to the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals, which found the warrantless data collection had violated his constitutional rights under the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution, but declined to order a new trial because the evidence was collected in good faith. The Eleventh Circuit has since vacated this decision pending a rehearing by the Eleventh Circuit en banc. United States v. Davis, 573 Fed. Appx. 925. On 5 May 2015, the en banc order upheld the use of the information. On 9th Nov 2015, the Supreme Court of the United States declined to hear this case on appeal.

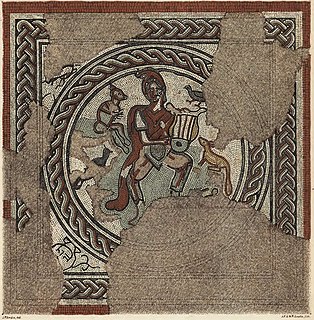

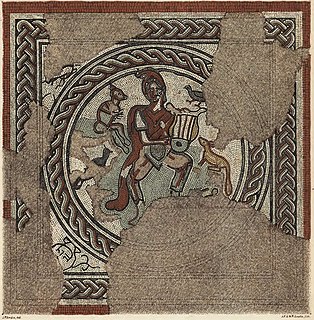

The mosaic theory is a legal doctrine in American courts for considering issues of information collection, government transparency, and search and seizure, especially in cases involving invasive or large-scale data collection by government entities. The theory takes its name from mosaic tile art: while an entire picture can be seen from a mosaic's tiles at a distance, no clear picture emerges from viewing a single tile in isolation. The mosaic theory calls for a cumulative understanding of data collection by law enforcement and analyzes searches "as a collective sequence of steps rather than individual steps."

The Email Privacy Act is a bill introduced in the United States Congress. The bipartisan proposed federal law was sponsored by Representative Kevin Yoder, a Republican from Kansas, and then-Representative Jared Polis, a Democrat of Colorado. The law is designed to update and reform existing online communications law, specifically the Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA) of 1986.

Microsoft Corp. v. United States, known on appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court as United States v. Microsoft Corp., 584 U.S. ___, 138 S. Ct. 1186 (2018), was a data privacy case involving the extraterritoriality of law enforcement seeking electronic data under the 1986 Stored Communications Act, Title II of the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 (ECPA), in light of modern computing and Internet technologies such as data centers and cloud storage.

Carpenter v. United States, 585 U.S. ____ (2018), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case concerning the privacy of historical cell site location information (CSLI). The Court held, in a 5–4 decision authored by Chief Justice Roberts, that the government violates the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution by accessing historical CSLI records containing the physical locations of cellphones without a search warrant.

Digital Search and Seizure refers to the ability of the United States Government to obtain and read an individual's private digital correspondence and material under The Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution.