A Tory is an individual who supports a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalist conservatism which upholds the established social order as it has evolved through the history of Great Britain. The Tory ethos has been summed up with the phrase "God, King, and Country". Tories are monarchists, were historically of a high church Anglican religious heritage, and were opposed to the liberalism of the Whig party.

The Irish Free State, also known by its Irish name Saorstát Éireann, was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between the forces of the Irish Republic – the Irish Republican Army (IRA) – and British Crown forces.

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was a sovereign state in Northwestern Europe that was established by the union in 1801 of the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland. The establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922 led to the remainder later being renamed the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in 1927.

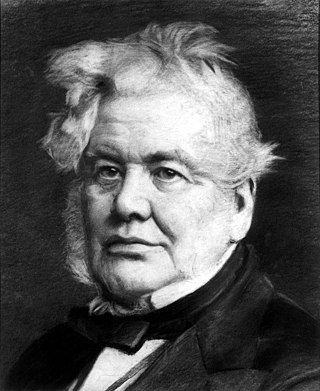

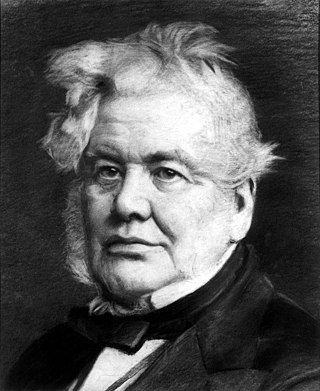

Isaac Butt was an Irish barrister, editor, politician, Member of Parliament in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, economist and the founder and first leader of a number of Irish nationalist parties and organisations. He was a leader in the Irish Metropolitan Conservative Society in 1836, the Home Government Association in 1870, and the Home Rule League in 1873. Colin W. Reid argues that Home Rule was the mechanism Butt proposed to bind Ireland to Great Britain. It would end the ambiguities of the Act of Union of 1800. He portrayed a federalised United Kingdom, which would have weakened Irish exceptionalism within a broader British context. Butt was representative of a constructive national unionism. As an economist, he made significant contributions regarding the potential resource mobilisation and distribution aspects of protection, and analysed deficiencies in the Irish economy such as sparse employment, low productivity, and misallocation of land. He dissented from the established Ricardian theories and favoured some welfare state concepts. As editor he made the Dublin University Magazine a leading Irish journal of politics and literature.

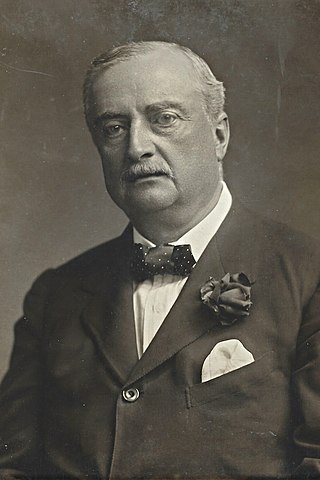

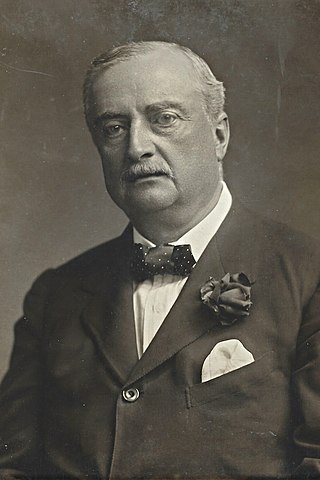

John Edward Redmond was an Irish nationalist politician, barrister, and MP in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom. He was best known as leader of the moderate Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) from 1900 until his death in 1918. He was also the leader of the paramilitary organisation the Irish National Volunteers (INV).

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cultural nationalism based on the principles of national self-determination and popular sovereignty. Irish nationalists during the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries such as the United Irishmen in the 1790s, Young Irelanders in the 1840s, the Fenian Brotherhood during the 1880s, Fianna Fáil in the 1920s, and Sinn Féin styled themselves in various ways after French left-wing radicalism and republicanism. Irish nationalism celebrates the culture of Ireland, especially the Irish language, literature, music, and sports. It grew more potent during the period in which all of Ireland was part of the United Kingdom, which led to most of the island gaining independence from the UK in 1922.

Irish republicanism is the political movement for an Irish republic, void of any British rule. Throughout its centuries of existence, it has encompassed various tactics and identities, simultaneously elective and militant and has been both widely supported and iconoclastic.

The Imperial Federation was a series of proposals in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to create a federal union to replace the existing British Empire, presenting it as an alternative to colonial imperialism. No such proposal was ever adopted, but various schemes were popular in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and other colonial territories. The project was championed by Unionists such as Joseph Chamberlain as an alternative to William Gladstone's proposals for home rule in Ireland.

The 1921 Irish elections took place in Ireland on 24 May 1921 to elect members of the House of Commons of Northern Ireland and the House of Commons of Southern Ireland. These legislatures had been established by the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which granted Home Rule to a partitioned Ireland within the United Kingdom.

The Irish Unionist Alliance (IUA), also known as the Irish Unionist Party, Irish Unionists or simply the Unionists, was a unionist political party founded in Ireland in 1891 from a merger of the Irish Conservative Party and the Irish Loyal and Patriotic Union (ILPU) to oppose plans for home rule for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The party was led for much of its existence by Colonel Edward James Saunderson and later by St John Brodrick, 1st Earl of Midleton. In total, eighty-six members of the House of Lords affiliated themselves with the Irish Unionist Alliance, although its broader membership among Irish voters outside Ulster was relatively small.

Stephen Lucius Gwynn was an Irish journalist, biographer, author, poet and Protestant Nationalist politician. As a member of the Irish Parliamentary Party he represented Galway city as its Member of Parliament from 1906 to 1918. He served as a British Army officer in France during World War I and was a prominent proponent of Irish involvement in the Allied war effort. He founded the Irish Centre Party in 1919, but his moderate nationalism was eclipsed by the growing popularity of Sinn Féin.

Ulster nationalism is a minor school of thought in the politics of Northern Ireland that seeks the independence of Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom without joining the Republic of Ireland, thereby becoming an independent sovereign state separate from both.

The Partition of Ireland was the process by which the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (UK) divided Ireland into two self-governing polities: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland. It was enacted on 3 May 1921 under the Government of Ireland Act 1920. The Act intended both territories to remain within the United Kingdom and contained provisions for their eventual reunification. The smaller Northern Ireland was duly created with a devolved government and remained part of the UK. The larger Southern Ireland was not recognised by most of its citizens, who instead recognised the self-declared 32-county Irish Republic. On 6 December 1922, Ireland was partitioned. At that time, the territory of Southern Ireland left the UK and became the Irish Free State, now known as the Republic of Ireland. Ireland had a large Catholic, nationalist majority who wanted self-governance or independence. Prior to partition the Irish Home Rule movement compelled the British Parliament to introduce bills that would give Ireland a devolved government within the UK. This led to the Home Rule Crisis (1912–14), when Ulster unionists/loyalists founded a large paramilitary organization, the Ulster Volunteers, that could be used to prevent Ulster from being ruled by an Irish government. The British government proposed to exclude all or part of Ulster, but the crisis was interrupted by the First World War (1914–18). Support for Irish independence grew during the war and after the 1916 armed rebellion known as the Easter Rising.

William Martin Murphy was an Irish businessman, newspaper publisher and politician. A member of parliament (MP) representing Dublin from 1885 to 1892, he was dubbed "William Murder Murphy" among the Irish press and the striking members of the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union during the Dublin Lockout of 1913. He was arguably both Ireland's first "press baron" and the leading promoter of tram development.

The Irish Convention was an assembly which sat in Dublin, Ireland from July 1917 until March 1918 to address the Irish question and other constitutional problems relating to an early enactment of self-government for Ireland, to debate its wider future, discuss and come to an understanding on recommendations as to the best manner and means this goal could be achieved. It was a response to the dramatically altered Irish political climate after the 1916 rebellion and was proposed by David Lloyd George, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, in May 1917 to John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, announcing that "Ireland should try her hand at hammering out an instrument of government for her own people".

Frederick Scott Oliver, known as F. S. Oliver, was a prominent Scottish political writer and businessman who advocated tariff reform and imperial union for the British Empire. He played an important role in the Round Table movement, collaborated in the downfall of Prime Minister H. H. Asquith's wartime government and its replacement by David Lloyd George in 1916, and pressed for "home rule all round" to resolve the political conflict between Britain and Irish nationalists.

The Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the end of World War I.

The Irish Dominion League was an Irish political party and movement in Britain and Ireland which advocated Dominion status for Ireland within the British Empire, and opposed partition of Ireland into separate southern and northern jurisdictions. It attracted modest support from middle-class Dubliners of moderate unionist and nationalist backgrounds, anxious to achieve a compromise in the face of the escalating conflict between the Irish Republican Army and the British. It operated between 1919 and 1921.

The Unionist Anti-Partition League (UAPL) was a unionist political organisation in Ireland which campaigned for a united Ireland within the United Kingdom. Led by St John Brodrick, 1st Earl of Midleton, it split from the Irish Unionist Alliance on 24 January 1919 over disagreements regarding the partition of Ireland.

In 20th century politics, Winston Churchill (1874–1965) was one of the world's most influential and significant figures. He was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945, when he led the country to victory in the Second World War, and again from 1951 to 1955. Apart from two years between 1922 and 1924, he was a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1900 to 1964. Ideologically an economic liberal and imperialist, he was for most of his career a member of the Conservative Party, and its leader from 1940 to 1955. He was a member of the Liberal Party from 1904 to 1924.