Related Research Articles

The Nation was an Irish nationalist weekly newspaper, published in the 19th century. The Nation was printed first at 12 Trinity Street, Dublin from 15 October 1842 until 6 January 1844. The paper was afterwards published at 4 D'Olier Street from 13 July 1844, to 28 July 1848, when the issue for the following day was seized and the paper suppressed. It was published again in Middle Abbey Street on its revival in September 1849.

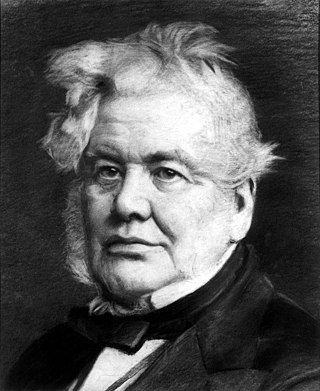

Daniel O'Connell (I) (Irish: Dónall Ó Conaill; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), hailed in his time as The Liberator, was the acknowledged political leader of Ireland's Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th century. His mobilization of Catholic Ireland, down to the poorest class of tenant farmers, secured the final installment of Catholic emancipation in 1829 and allowed him to take a seat in the United Kingdom Parliament to which he had been twice elected.

Isaac Butt was an Irish barrister, editor, politician, Member of Parliament in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, economist and the founder and first leader of a number of Irish nationalist parties and organisations. He was a leader in the Irish Metropolitan Conservative Society in 1836, the Home Government Association in 1870, and the Home Rule League in 1873. Colin W. Reid argues that Home Rule was the mechanism Butt proposed to bind Ireland to Great Britain. It would end the ambiguities of the Act of Union of 1800. He portrayed a federalised United Kingdom, which would have weakened Irish exceptionalism within a broader British context. Butt was representative of a constructive national unionism. As an economist, he made significant contributions regarding the potential resource mobilisation and distribution aspects of protection, and analysed deficiencies in the Irish economy such as sparse employment, low productivity, and misallocation of land. He dissented from the established Ricardian theories and favoured some welfare state concepts. As editor he made the Dublin University Magazine a leading Irish journal of politics and literature.

Thomas Osborne Davis was an Irish writer; with Charles Gavan Duffy and John Blake Dillon, a founding editor of The Nation, the weekly organ of what came to be known as the Young Ireland movement. While embracing the common cause of a representative, national government for Ireland, Davis took issue with the nationalist leader Daniel O'Connell by arguing for the common ("mixed") education of Catholics and Protestants and by advocating for Irish as the national language.

The Society of United Irishmen was a sworn association in the Kingdom of Ireland formed in the wake of the French Revolution to secure "an equal representation of all the people" in a national government. Despairing of constitutional reform, in 1798 the United Irishmen instigated a republican insurrection in defiance of British Crown forces and of Irish sectarian division. Their suppression was a prelude to the abolition of the Protestant Ascendancy Parliament in Dublin and to Ireland's incorporation in a United Kingdom with Great Britain. An attempt to revive the movement and renew the insurrection following the Acts of Union was defeated in 1803.

West Brit, an abbreviation of West Briton, is a derogatory term for an Irish person who is perceived as Anglophilic in matters of culture or politics. West Britain is a description of Ireland emphasising it as under British influence.

Sir Charles Gavan Duffy, KCMG, PC, was an Irish poet and journalist, Young Irelander and tenant-rights activist. After emigrating to Australia in 1856 he entered the politics of Victoria on a platform of land reform, and in 1871–1872 served as the colony's 8th Premier.

Ireland was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 1801 to 1922. For almost all of this period, the island was governed by the UK Parliament in London through its Dublin Castle administration in Ireland. Ireland underwent considerable difficulties in the 19th century, especially the Great Famine of the 1840s which started a population decline that continued for almost a century. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a vigorous campaign for Irish Home Rule. While legislation enabling Irish Home Rule was eventually passed, militant and armed opposition from Irish unionists, particularly in Ulster, opposed it. Proclamation was shelved for the duration following the outbreak of World War I. By 1918, however, moderate Irish nationalism had been eclipsed by militant republican separatism. In 1919, war broke out between republican separatists and British Government forces. Subsequent negotiations between Sinn Féin, the major Irish party, and the UK government led to the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which resulted in five-sixths of Ireland seceding from the United Kingdom.

The Protestant Ascendancy, also known simply as the Ascendancy, was the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland between the 17th century and the early 20th century by a minority of landowners, Protestant clergy, and members of the professions, all members of the Established Church. The Ascendancy excluded other groups from politics and the elite, most numerous among them Roman Catholics but also members of the Presbyterian and other Protestant denominations, along with non-Christians such as Jews, until the Reform Acts (1832–1928).

Young Ireland was a political and cultural movement in the 1840s committed to an all-Ireland struggle for independence and democratic reform. Grouped around the Dublin weekly The Nation, it took issue with the compromises and clericalism of the larger national movement, Daniel O'Connell's Repeal Association, from which it seceded in 1847. Despairing, in the face of the Great Famine, of any other course, in 1848 Young Irelanders attempted an insurrection. Following the arrest and the exile of most of their leading figures, the movement split between those who carried the commitment to "physical force" forward into the Irish Republican Brotherhood, and those who sought to build a "League of North and South" linking an independent Irish parliamentary party to tenant agitation for land reform.

The Catholic Relief Act 1829, also known as the Catholic Emancipation Act 1829, was passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1829. It was the culmination of the process of Catholic emancipation throughout the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

Dr. Robert Cane (1807–1858), was born in Kilkenny, Ireland in 1807. He was a member of the Repeal Association and the Irish Confederation. He qualified as an M.D. in 1836, became a member of Kilkenny Corporation and was Mayor twice.

The history of Ireland from 1691–1800 was marked by the dominance of the Protestant Ascendancy. These were Anglo-Irish families of the Anglican Church of Ireland, whose English ancestors had settled Ireland in the wake of its conquest by England and colonisation in the Plantations of Ireland, and had taken control of most of the land. Many were absentee landlords based in England, but others lived full-time in Ireland and increasingly identified as Irish.. During this time, Ireland was nominally an autonomous Kingdom with its own Parliament; in actuality it was a client state controlled by the King of Great Britain and supervised by his cabinet in London. The great majority of its population, Roman Catholics, were excluded from power and land ownership under the penal laws. The second-largest group, the Presbyterians in Ulster, owned land and businesses but could not vote and had no political power. The period begins with the defeat of the Catholic Jacobites in the Williamite War in Ireland in 1691 and ends with the Acts of Union 1800, which formally annexed Ireland in a United Kingdom from 1 January 1801 and dissolved the Irish Parliament.

In the history of Ireland, the Penal Laws was a series of laws imposed in an attempt to force Irish Catholics and to lesser extent Protestant dissenter planters and Quakers to accept the established Church of Ireland. These laws notably included the Education Act 1695, the Banishment Act 1697, the Registration Act 1704, the Popery Acts 1704 and 1709, and the Disenfranchising Act 1728. The majority of the penal laws were removed in the period 1778–1793 with the last of them of any significance being removed in 1829. Notwithstanding those previous enactments, the Government of Ireland Act 1920 contained an all-purpose provision in section 5 removing any that might technically still then be in existence.

The Irish Conservative Party, often called the Irish Tories, was one of the dominant Irish political parties in Ireland in the 19th century. It was affiliated with the Conservative Party in Great Britain. Throughout much of the century it and the Irish Liberal Party were rivals for electoral dominance among Ireland's small electorate within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, with parties such as the movements of Daniel O'Connell and later the Independent Irish Party relegated into third place. The Irish Conservatives became the principal element of the Irish Unionist Alliance following the alliance's foundation in 1891.

William Sharman Crawford (1780–1861) was an Irish landowner who, in the Parliament of the United Kingdom, championed a democratic franchise, a devolved legislature for Ireland, and the interests of the Irish tenant farmer. As a Radical representing first, with Daniel O'Connell's endorsement, Dundalk (1835-1837) and then, with the support of Chartists, the English constituency of Rochdale (1841–1852) he introduced bills to codify and extend in Ireland the Ulster tenant right. In his last electoral contest, standing on the platform of the all-Ireland Tenant Right League in 1852 he failed to unseat the Conservative and Orange party in Down, his native county.

Henry Cooke (1788–1868) was an Irish Presbyterian minister of the early and mid-nineteenth century.

George Ensor J.P. was an eminent Irish lawyer and radical political pamphleteer. Among other conservative precepts, he pilloried the Malthusian doctrine that poverty is sustained by the “disposition to breed". As a hindrance to enterprise and prosperity, he pointed rather to the tyranny of concentrated wealth. In Ireland, it was condition he believed could be reversed only through popular representation in a restored parliament. Ensor further outraged prevailing opinion by inveighing against the constitutional ascendancy not merely of Protestantism, but more broadly of the Christian religion. He argued that questions of morality and social justice cannot be addressed within a theology of salvation through faith.

The Irish Patriot Party was the name of a number of different political groupings in Ireland throughout the 18th century. They were primarily supportive of Whig concepts of personal liberty combined with an Irish identity that rejected full independence, but advocated strong self-government within the British Empire.

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the end of World War I.

References

- ↑ The Dublin University magazine, vol. 8 (William Curry, Jun. & Co, 1836), p. 738

- ↑ Boyton, Charles Dictionary of Irish Biography

- ↑ Report of the proceedings at the first public meeting of the Irish Metropolitan Conservative Society: held at their house, 19, Dawson-Street, on the 16th of November, 1836 (Printed for the Society by C. F. Goodwin, 33, Eustace-Street, 1836, 47 pages)

- ↑ Alvin Jackson, Ireland 1798-1998: War, Peace and Beyond (2010), p. 60

- ↑ The Spectator , vol. 17, p. 464

- ↑ W. J. McCormack, From Burke to Beckett : Ascendancy, Tradition and Betrayal in Literary History (Cork University Press, 1994/2004) ISBN 0-902561-94-4