Related Research Articles

The American Revolution was a rebellion and political movement in the Thirteen Colonies which peaked when colonists initiated an ultimately successful war for independence against the Kingdom of Great Britain. Leaders of the American Revolution were colonial separatist leaders who originally sought more autonomy as British subjects, but later assembled to support the Revolutionary War, which ended British colonial rule over the colonies, establishing their independence, and leading to the creation of the United States.

The Thirteen Colonies were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America during the 17th and 18th centuries. Grievances against the imperial government led the 13 colonies to begin uniting in 1774, and expelling British officials by 1775. Assembled at the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia, they appointed George Washington as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army to fight the American Revolutionary War. In 1776, Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence as the United States of America. Defeating British armies with French help, the Thirteen Colonies gained sovereignty with the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

The Mid-Atlantic is a region of the United States located in the overlap between the Northeastern and Southeastern states of the United States. Its exact definition differs upon source, but the region typically includes Delaware, the District of Columbia, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia with other sources including or excluding other states or areas in the Northeast and Southeast. The region has its origin in the Middle Colonies of the 18th century, its states being among the Thirteen Colonies of pre-revolutionary British America. As of the 2020 census, the region had a population of 60,783,913, representing slightly over 18% of the nation's population.

The history of the United States from 1776 to 1789 was marked by the nation's transition from the American Revolutionary War to the establishment of a novel constitutional order.

The colonial history of the United States covers the period of European colonization of North America from the early 16th century until the incorporation of the Thirteen Colonies into the United States in 1776 during the Revolutionary War. In the late 16th century, England, France, Spain, and the Dutch Republic launched major colonization expeditions in North America. The death rate was very high among early immigrants, and some early attempts disappeared altogether, such as the English Lost Colony of Roanoke. Nevertheless, successful colonies were established within several decades.

The Middle Colonies were a subset of the Thirteen Colonies in British America, located between the New England Colonies and the Southern Colonies. Along with the Chesapeake Colonies, this area now roughly makes up the Mid-Atlantic states.

The governments of the Thirteen Colonies of British America developed in the 17th and 18th centuries under the influence of the British constitution. After the Thirteen Colonies had become the United States, the experience under colonial rule would inform and shape the new state constitutions and, ultimately, the United States Constitution.

Triangular trade or triangle trade is a historical term indicating trade among three ports or regions. Triangular trade usually evolves when a region has export commodities that are not required in the region from which its major imports come. Triangular trade thus provides a method for rectifying trade imbalances between the above regions.

The Province of North Carolina, originally known as Albemarle Province, was a proprietary colony and later royal colony of Great Britain that existed in North America from 1712 to 1776.(p. 80) It was one of the five Southern colonies and one of the thirteen American colonies. The monarch of Great Britain was represented by the Governor of North Carolina, until the colonies declared independence on July 4, 1776.

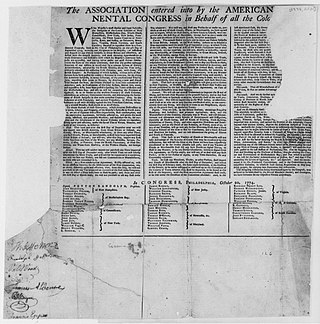

The Continental Association, also known as the Articles of Association or simply the Association, was an agreement among the American colonies adopted by the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia on October 20, 1774. It was a result of the escalating American Revolution and called for a trade boycott against British merchants by the colonies. Congress hoped that placing economic sanctions on British imports and exports would pressure Parliament into addressing the colonies' grievances, especially repealing the Intolerable Acts, which were strongly opposed by the colonies.

The Currency Act or Paper Bills of Credit Act is one of several Acts of the Parliament of Great Britain that regulated paper money issued by the colonies of British America. The Acts sought to protect British merchants and creditors from being paid in depreciated colonial currency. The policy created tension between the colonies and Great Britain and was cited as a grievance by colonists early in the American Revolution. However, the consensus view among modern economic historians and economists is that the debts by colonists to British merchants were not a major cause of the Revolution. In 1995, a random survey of 178 members of the Economic History Association found that 92% of economists and 74% of historians disagreed with the statement, "The debts owed by colonists to British merchants and other private citizens constituted one of the most powerful causes leading to the Revolution."

The American Enlightenment was a period of intellectual and philosophical fervor in the thirteen American colonies in the 18th to 19th century, which led to the American Revolution and the creation of the United States. The American Enlightenment was influenced by the 17th- and 18th-century Age of Enlightenment in Europe and native American philosophy. According to James MacGregor Burns, the spirit of the American Enlightenment was to give Enlightenment ideals a practical, useful form in the life of the nation and its people.

The Atlantic World comprises the interactions among the peoples and empires bordering the Atlantic Ocean rim from the beginning of the Age of Discovery to the early 19th century. Atlantic history is split between three different contexts: trans-Atlantic history, meaning the international history of the Atlantic World; circum-Atlantic history, meaning the transnational history of the Atlantic World; and cis-Atlantic history within an Atlantic context. The Atlantic slave trade continued into the 19th century, but the international trade was largely outlawed in 1807 by Britain. Slavery ended in 1865 in the United States and in the 1880s in Brazil (1888) and Cuba (1886). While some scholars stress that the history of the "Atlantic World" culminates in the "Atlantic Revolutions" of the late 18th early 19th centuries, the most influential research in the field examines the slave trade and the study of slavery, thus in the late-19th century terminus as part of the transition from Atlantic history to globalization seems most appropriate.

Tobacco and Slaves: The Development of Southern Cultures in the Chesapeake, 1680–1800, is a book written by historian Allan Kulikoff. Published in 1986, it is the first major study that synthesized the historiography of the colonial Chesapeake region of the United States. Tobacco and Slaves is a neo-Marxist study that explains the creation of a racial caste system in the tobacco-growing regions of Maryland and Virginia and the origins of southern slave society. Kulikoff uses statistics compiled from colonial court and church records, tobacco sales, and land surveys to conclude that economic, political, and social developments in the 18th-century Chesapeake established the foundations of economics, politics, and society in the 19th-century South.

The "rights of Englishmen" are the traditional rights of English subjects and later English-speaking subjects of the British Crown.

Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania is a series of essays written by the Pennsylvania lawyer and legislator John Dickinson (1732–1808) and published under the pseudonym "A Farmer" from 1767 to 1768. The twelve letters were widely read and reprinted throughout the Thirteen Colonies, and were important in uniting the colonists against the Townshend Acts in the run-up to the American Revolution. According to many historians, the impact of the Letters on the colonies was unmatched until the publication of Thomas Paine's Common Sense in 1776. The success of the letters earned Dickinson considerable fame.

Atlantic history is a specialty field in history that studies the Atlantic World in the early modern period. The Atlantic World was created by the contact between Europeans and the Americas, and Atlantic History is the study of that world. It is premised on the idea that, following the rise of sustained European contact with the New World in the 16th century, the continents that bordered the Atlantic Ocean—the Americas, Europe, and Africa—constituted a regional system or common sphere of economic and cultural exchange that can be studied as a totality.

The historiography of the British Empire refers to the studies, sources, critical methods and interpretations used by scholars to develop a history of the British Empire. Historians and their ideas are the main focus here; specific lands and historical dates and episodes are covered in the article on the British Empire. Scholars have long studied the Empire, looking at the causes for its formation, its relations to the French and other empires, and the kinds of people who became imperialists or anti-imperialists, together with their mindsets. The history of the breakdown of the Empire has attracted scholars of the histories of the United States, the British Raj, and the African colonies. John Darwin (2013) identifies four imperial goals: colonising, civilising, converting, and commerce.

Oliver Morton Dickerson was an American historian, author, and educator. Like his fellow historians Charles McLean Andrews and Lawrence Henry Gipson, Dickerson was a proponent of the "Imperial school" of historians who believed that the American colonies could not be studied or understood except as part of the British Empire. Among his publications were works on the British Board of Trade, the Navigation Acts, and Boston under military rule.

Peter S. Onuf is an American historian and professor known for his work on U.S. President Thomas Jefferson and Federalism. In 1989, he was named the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation Professor of the University of Virginia, a chair he held until retiring in 2012. The chair's previous occupants included Jefferson biographers Dumas Malone and Merrill D. Peterson; he was succeeded by Alan Taylor.

References

- ↑ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2022-03-31.

- ↑ "Jack P. Greene". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. Retrieved 2022-03-31.

- ↑ Greene, “The Making of a Historian: Some Autobiographical Notes,” in John B. Boles, ed., Shapers of Southern History (Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 2004), 18-39.

- ↑ e.g. “The American Revolution,” The American Historical Review 105:1 (Feb. 2000)

- ↑ many of those essays were eventually collected and published in his book Interpreting Early America (1996)

- ↑ Imperatives, Behaviors and Identity (1992); Negotiated Authorities (1994); Understanding the American Revolution (1995); Interpreting Early America (1996)

- ↑ M. D. Cruz (2019). "Atlantic History and Other Approaches to Early Modern Empires: a Conversation with Jack P. Greene". Ler Historia. 75 (2019): 231–250. doi: 10.4000/lerhistoria.6020 . hdl: 10451/43898 . ISSN 0870-6182.

- ↑ "Jack P. Greene: A Comprehensive Bibliography" (Baltimore, MD: The Department of History at Johns Hopkins University, 2004)