Related Research Articles

Punctuation marks are marks indicating how a piece of written text should be read and, consequently, understood. The oldest known examples of punctuation marks were found in the Mesha Stele from the 9th century BC, consisting of points between the words and horizontal strokes between sections. The alphabet-based writing began with no spaces, no capitalization, no vowels, and with only a few punctuation marks, as it was mostly aimed at recording business transactions. Only with the Greek playwrights did the ends of sentences begin to be marked to help actors know when to make a pause during performances. Punctuation includes space between words and the other, historically or currently used, signs.

The comma, is a punctuation mark that appears in several variants in different languages. It has the same shape as an apostrophe or single closing quotation mark in many typefaces, but it differs from them in being placed on the baseline of the text. Some typefaces render it as a small line, slightly curved or straight, but inclined from the vertical. Other fonts give it the appearance of a miniature filled-in figure 9 on the baseline.

The colon, :, is a punctuation mark consisting of two equally sized dots aligned vertically. A colon often precedes an explanation, a list, or a quoted sentence. It is also used between hours and minutes in time, between certain elements in medical journal citations, between chapter and verse in Bible citations, and, in the US, for salutations in business letters and other formal letter writing.

The question mark? is a punctuation mark that indicates a question or interrogative clause or phrase in many languages.

The semicolon; is a symbol commonly used as orthographic punctuation. In the English language, a semicolon is most commonly used to link two independent clauses that are closely related in thought, such as when restating the preceding idea with a different expression. When a semicolon joins two or more ideas in one sentence, those ideas are then given equal rank. Semicolons can also be used in place of commas to separate items in a list, particularly when the elements of the list themselves have embedded commas.

In writing, a space is a blank area that separates words, sentences, syllables and other written or printed glyphs (characters). Conventions for spacing vary among languages, and in some languages the spacing rules are complex. Inter-word spaces ease the reader's task of identifying words, and avoid outright ambiguities such as "now here" vs. "nowhere". They also provide convenient guides for where a human or program may start new lines.

A garden-path sentence is a grammatically correct sentence that starts in such a way that a reader's most likely interpretation will be incorrect; the reader is lured into a parse that turns out to be a dead end or yields a clearly unintended meaning. "Garden path" refers to the saying "to be led down [or up] the garden path", meaning to be deceived, tricked, or seduced. In A Dictionary of Modern English Usage (1926), Fowler describes such sentences as unwittingly laying a "false scent".

In English-language punctuation, a serial comma is a comma placed immediately after the penultimate term in a series of three or more terms. For example, a list of three countries might be punctuated as either "France, Italy and Spain" or "France, Italy, and Spain".

In written English usage, a comma splice or comma fault is the use of a comma to join two independent clauses. For example:

It is nearly half past five, we cannot reach town before dark.

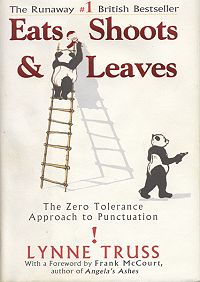

Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation is a non-fiction book written by Lynne Truss, the former host of BBC Radio 4's Cutting a Dash programme. In the book, published in 2003, Truss bemoans the state of punctuation in the United Kingdom and the United States and describes how rules are being relaxed in today's society. Her goal is to remind readers of the importance of punctuation in the English language by mixing humour and instruction.

In rhetoric, antanaclasis is the literary trope in which a single word or phrase is repeated, but in two different senses. Antanaclasis is a common type of pun, and like other kinds of pun, it is often found in slogans.

An interrogative clause is a clause whose form is typically associated with question-like meanings. For instance, the English sentence "Is Hannah sick?" has interrogative syntax which distinguishes it from its declarative counterpart "Hannah is sick". Also, the additional question mark closing the statement assures that the reader is informed of the interrogative mood. Interrogative clauses may sometimes be embedded within a phrase, for example: "Paul knows who is sick", where the interrogative clause "who is sick" serves as complement of the embedding verb "know".

Sentence spacing concerns how spaces are inserted between sentences in typeset text and is a matter of typographical convention. Since the introduction of movable-type printing in Europe, various sentence spacing conventions have been used in languages with a Latin alphabet. These include a normal word space, a single enlarged space, and two full spaces.

"Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo" is a grammatically correct sentence in English that is often presented as an example of how homonyms and homophones can be used to create complicated linguistic constructs through lexical ambiguity. It has been discussed in literature in various forms since 1967, when it appeared in Dmitri Borgmann's Beyond Language: Adventures in Word and Thought.

The full stop, period, or full point. is a punctuation mark used for several purposes, most often to mark the end of a declarative sentence.

The history of sentence spacing is the evolution of sentence spacing conventions from the introduction of movable type in Europe by Johannes Gutenberg to the present day.

Punctuation in the English language helps the reader to understand a sentence through visual means other than just the letters of the alphabet. English punctuation has two complementary aspects: phonological punctuation, linked to how the sentence can be read aloud, particularly to pausing; and grammatical punctuation, linked to the structure of the sentence. In popular discussion of language, incorrect punctuation is often seen as an indication of lack of education and of a decline of standards.

In grammar, sentence and clause structure, commonly known as sentence composition, is the classification of sentences based on the number and kind of clauses in their syntactic structure. Such division is an element of traditional grammar.

The compound point is an obsolete typographical construction. Keith Houston reported that this form of punctuation doubling, which involved the comma dash (,—), the semicolon dash (;—), the colon dash, or "dog's bollocks" (:—), and less often the stop-dash (.—) arose in the seventeenth century, citing examples from as early as 1622. More traditionally, these paired forms of punctuation seem most often to have been called (generically) compound points and (specifically) semicolon dash, comma dash, colon dash, and point dash.

References

- 1 2 Magonet, Jonathan (2004). A rabbi reads the Bible (2nd ed.). SCM-Canterbury Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-334-02952-6 . Retrieved 30 April 2009.

You may remember an old classroom test in English language. What punctuation marks do you have to add to this sentence so as to make sense of it?

- 1 2 Dundes, Alan; Pagter, Carl R. (1987). When you're up to your ass in alligators: more urban folklore from the paperwork empire (Illustrated ed.). Wayne State University Press. p. 135. ISBN 0-8143-1867-3 . Retrieved 30 April 2009.

The object of this and similar tests is to make sense of a series of words by figuring out the correct intonation pattern.

- ↑ Hudson, Grover (1999). Essential introductory linguistics. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 372. ISBN 0-631-20304-4 . Retrieved 30 April 2009.

Writing is secondary to speech, in history and in the fact that speech and not writing is fundamental to the human species.

- ↑ van de Velde, Roger G. (1992). Text and thinking: on some roles of thinking in text interpretation (Illustrated ed.). Walter de Gruyter. p. 43. ISBN 3-11-013250-8 . Retrieved 30 April 2009.

In scanning across lines, readers also make use of the information parts carried along with the punctuation markes[ sic ]: a period, a dash, a colon, a semicolon or a comma may signal different degrees of integration/separation between the groupings.

- ↑ Sterbenz, Christina (8 January 2014). "9 Sentences That Are Perfectly Accurate". Business Insider Australia. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ↑ "Problem C: Operator Jumble". 31st ACM International Collegiate Programming Conference, 2006–2007.

- ↑ Amon, Mike (28 January 2004). "GADFLY". Financial Times. Retrieved 30 April 2009.

HAD up to here? So were readers of last week's column, invited to punctuate "Smith where Jones had had had had had had had had had had had the examiners approval."

- ↑ Jackson, Howard (2002). Grammar and Vocabulary: A Resource Book for Students. Routledge. p. 123. ISBN 0-415-23170-1 . Retrieved 30 April 2009.

Finally, verbal humour is often an ingredient of puzzles. As part of an advertising campaign for its educational website <learn.co.uk>, the Guardian (for 3 January 2001) included the following familiar grammatical puzzle.

- ↑ 3802 – Operator Jumble Archived 13 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Reichenbach, Hans (1947) Elements of Symbolic logic. London: Collier-MacMillan. Exercise 3–4, p. 405; solution p. 417.

- ↑ Weick, Karl E. (2005). Making Sense of the Organization (8th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 186–187. ISBN 0-631-22319-3 . Retrieved 30 April 2009.

Once a person has generated/bracketed part of the stream, then the activities of punctuation and connection (parsing) can occur to transform the raw data into information.

- ↑ Lecercle, Jean-Jacques (1990). The violence of language (Illustrated ed.). Routledge. p. 86. ISBN 0-415-03431-0 . Retrieved 30 April 2009.

Suppose I decide that I wish to make up a sentence containing eleven occurrences of the word 'had' in a row ...

- ↑ Hollin, Clive R. (1995). Contemporary Psychology: An Introduction (Illustrated ed.). Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 0-7484-0191-1 . Retrieved 30 April 2009.

Do readers make use of the ways in which sentences are structured?

- ↑ Fforde, Jasper (2003). The Well of Lost Plots. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 9781844569212 . Retrieved 30 April 2012.