Related Research Articles

Thābit ibn Qurra ; 826 or 836 – February 19, 901, was a mathematician, physician, astronomer, and translator who lived in Baghdad in the second half of the ninth century during the time of the Abbasid Caliphate.

Munishvara or Munīśvara Viśvarūpa was an Indian mathematician who wrote several commentaries including one on astronomy Siddhanta Sarvabhauma (1646) which included descriptions of astronomical instruments such as the pratoda yantra. Another commentary was Lilavativivruti. Very little is known about his other than that he came from a family of astronomers including his father Ranganatha who wrote a commentary called Gụ̄hārthaprakaśa/Gūḍhārthaprakāśikā, a commentary on the Suryasiddhanta. His grandfather Ballala had his origins in Dadhigrama in Vidharba and had moved to Benares and several sons wrote commentaries on astronomy and mathematics. Munisvara's Siddhantasarvabhauma had the patronage of Shah Jahan like his paternal uncle Krishna Daivagna. He was opposed to fellow mathematician Kamalakara whose brother also wrote a critique of Munisvara's bhangi-vibhangi method for planetary motions. He was also opposed to the adoption of some mathematical ideas in spherical trigonometry from Arab scholars. An edition of his Siddhanta Sarvabhauma was published from the Princess of Wales Sarasvati Bhavana Granthamala edited by Gopinath Kaviraj. Munisvara's book had twelve chapters in two parts. The second part had notes on astronomical instruments. He was a follower of Bhaskara II.

Greek mathematics refers to mathematics texts and ideas stemming from the Archaic through the Hellenistic and Roman periods, mostly attested from the late 7th century BC to the 4th century AD, around the shores of the Mediterranean. Greek mathematicians lived in cities spread over the entire region, from Anatolia (Turkey) to Italy and North Africa, but were united by Greek culture and the Greek language. The study of mathematics for its own sake and the use of generalized mathematical theories and proofs is an important difference between Greek mathematics and those of preceding civilizations.

Sharaf al-Dīn al-Muẓaffar ibn Muḥammad ibn al-Muẓaffar al-Ṭūsī was an Iranian mathematician and astronomer of the Islamic Golden Age.

Abu Amir Yusuf ibn Ahmad ibn Hud, more commonly known as al-Mu'taman, was a mathematician, and also one of the kings of the Taifa of Zaragoza. The name al-Mu'taman is itself a shortening of his full regnal name al-Mu'taman Billah.

Mathematics during the Golden Age of Islam, especially during the 9th and 10th centuries, was built on Greek mathematics and Indian mathematics. Important progress was made, such as full development of the decimal place-value system to include decimal fractions, the first systematised study of algebra, and advances in geometry and trigonometry.

Joseph Diez Gergonne was a French mathematician and logician.

During the Renaissance, great advances occurred in geography, astronomy, chemistry, physics, mathematics, manufacturing, anatomy and engineering. The collection of ancient scientific texts began in earnest at the start of the 15th century and continued up to the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, and the invention of printing allowed a faster propagation of new ideas. Nevertheless, some have seen the Renaissance, at least in its initial period, as one of scientific backwardness. Historians like George Sarton and Lynn Thorndike criticized how the Renaissance affected science, arguing that progress was slowed for some amount of time. Humanists favored human-centered subjects like politics and history over study of natural philosophy or applied mathematics. More recently, however, scholars have acknowledged the positive influence of the Renaissance on mathematics and science, pointing to factors like the rediscovery of lost or obscure texts and the increased emphasis on the study of language and the correct reading of texts.

Gabriel Sudan was a Romanian mathematician, known for the Sudan function, an important example in the theory of computation, similar to the Ackermann function.

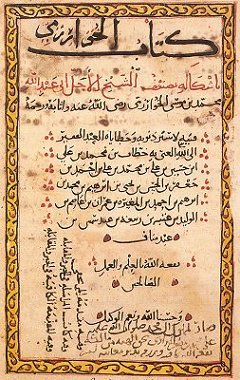

Al-Hassar or Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Abdallah ibn Ayyash al-Hassar was a 12th-century Moroccan mathematician. He is the author of two books Kitab al-bayan wat-tadhkar, a manual of calculation and Kitab al-kamil fi sinaat al-adad, on the breakdown of numbers. The first book is lost and only a part of the second book remains.

John of Tynemouth was a 13th-century mathematician and geometer.

The Quarterly Journal of Mathematics is a quarterly peer-reviewed mathematics journal established in 1930 from the merger of The Quarterly Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics and the Messenger of Mathematics. According to the Journal Citation Reports, the journal has a 2020 impact factor of 0.681.

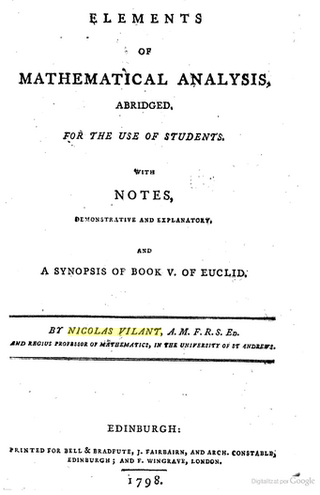

Nicolas Vilant FRSE (1737-1807) was a mathematician from Scotland in the 18th century, known for his textbooks. He was a joint founder of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1783.

Isabella Grigoryevna Bashmakova was a Russian historian of mathematics. In 2001, she was a recipient of the Alexander Koyré́ Medal of the International Academy of the History of Science.

Thomas W. Hawkins Jr. is an American historian of mathematics.

Matthew O'Brien (1814–1855) was an Irish mathematician.

Karl Mikhailovich Peterson was a Russian mathematician, known by an earlier formulation of the Gauss–Codazzi equations.

Erhard Scholz is a German historian of mathematics with interests in the history of mathematics in the 19th and 20th centuries, historical perspective on the philosophy of mathematics and science, and Hermann Weyl's geometrical methods applied to gravitational theory.

Judith Veronica Field is a British historian of science with interests in mathematics and the impact of science in art, an honorary visiting research fellow in the Department of History of Art of Birkbeck, University of London, former president of the British Society for the History of Mathematics, and president of the Leonardo da Vinci Society.

Hélène Bellosta-Baylet was a French historian of mathematics specializing in mathematics in medieval Islam.

References

- ↑ "Jan Hogendijk". Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ↑ EMS Prizes 2012