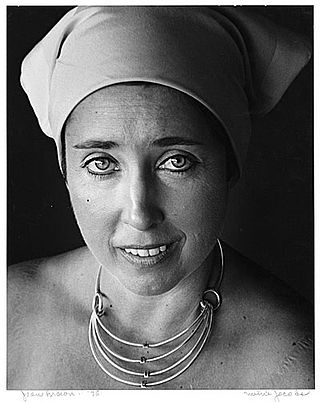

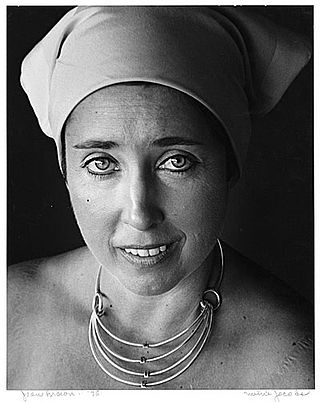

Joan Mitchell was an American artist who worked primarily in painting and printmaking, and also used pastel and made other works on paper. She was an active participant in the New York School of artists in the 1950s. A native of Chicago, she is associated with the American abstract expressionist movement, even though she lived in France for much of her career.

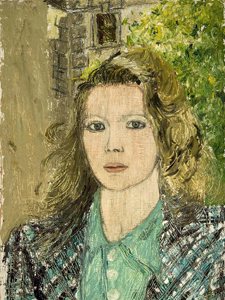

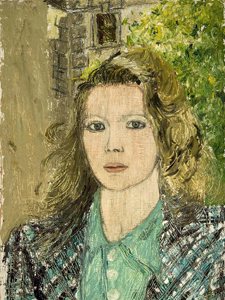

Joan Brown was an American figurative painter who lived and worked in Northern California. She was a member of the "second generation" of the Bay Area Figurative Movement.

Sylvia Sleigh was a Welsh-born naturalised American realist painter who lived and worked in New York City. She is known for her role in the feminist art movement and especially for reversing traditional gender roles in her paintings of nude men, often using conventional female poses from historical paintings by male artists like Diego Vélazquez, Titian, and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Her most well-known subjects were art critics, feminist artists, and her husband, Lawrence Alloway.

Wally Bill Hedrick was a seminal American artist in the 1950s California counterculture, gallerist, and educator who came to prominence in the early 1960s. Hedrick's contributions to art include pioneering artworks in psychedelic light art, mechanical kinetic sculpture, junk/assemblage sculpture, Pop Art, and (California) Funk Art. Later in his life, he was a recognized forerunner in Happenings, Conceptual Art, Bad Painting, Neo-Expressionism, and image appropriation. Hedrick was also a key figure in the first important public manifestation of the Beat Generation when he helped to organize the Six Gallery Reading, and created the first artistic denunciation of American foreign policy in Vietnam. Wally Hedrick was known as an “idea artist” long before the label “conceptual art” entered the art world, and experimented with innovative use of language in art, at times resorting to puns.

Kara Maria, née Kara Maria Sloat, is a San Francisco-based visual artist known for paintings, works on paper and printmaking. Her vivid, multi-layered paintings have been described as collages or mash-ups of contemporary art vocabularies, fusing a wide range of abstract mark-making with Pop art strategies of realism, comic-book forms, and appropriation. Her work outwardly conveys a sense of playfulness and humor that gives way to explicit or subtle examinations—sometimes described as "cheerfully apocalyptic"—of issues including ecological collapse, diminishing biodiversity, military violence and the sexual exploitation of women. In a 2021 review, Squarecylinder critic Jaimie Baron wrote, "Maria’s paintings must be read as satires [that] recognize the absurdities of our era … These pretty, playful paintings are indictments, epitaphs-to-be."

Julie Heffernan is an American painter whose work has been described by the writer Rebecca Solnit as "a new kind of history painting" and by The New Yorker as "ironic rococo surrealism with a social-satirical twist". Heffernan has been a Professor of Fine Arts at Montclair State University in Upper Montclair, New Jersey since 1997. She lives in New York, New York.

Brett Reichman is an American painter and educator. He was a professor at the San Francisco Art Institute where he taught both in the graduate and undergraduate programs. His work came to fruition in the late 1980s out of cultural activism that addressed the AIDS epidemic and gay identity politics and was curated into early exhibitions that acknowledged those formative issues. These exhibitions included Situation: Perspectives on Work by Lesbian and Gay Artists at New Langton Arts in San Francisco, The Anti-Masculine at the Kim Light Gallery in Los Angeles, Beyond Loss at the Washington Project for the Arts in Washington, D.C, and In A Different Light: Visual Culture, Sexual Identity, Queer Practice at the Berkeley Art Museum, Berkeley, California. However, after legislation passed in 1989 that restricted federal funding for art dealing with homosexuality and AIDS, artists like Reichman approached their themes subtly. His And the Spell Was Broken Somewhere Over the Rainbow is embellished with colors of the rainbow and presents three clocks. It references Oz while actually indirectly addressing the new reality that San Francisco could no longer be viewed as a land of enchantment due to the AIDS crisis. Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, he has lived and worked in San Francisco since 1984.

Anglim Trimble Gallery, formerly Gallery Paule Anglim, and Anglim Gilbert Gallery, is a contemporary commercial art gallery which is located at Minnesota Street Project, 1275 Minnesota Street, San Francisco, California The gallery was founded by Paule Anglim in the early 1970s.

Ann Agee is an American visual artist whose practice centers on ceramic figurines, objects and installations, hand-painted wallpaper drawings, and sprawling exhibitions that merge installation art, domestic environment and showroom. Her art celebrates everyday objects and experiences, decorative and utilitarian arts, and the dignity of work and craftsmanship, engaging issues involving gender, labor and fine art with a subversive, feminist stance. Agee's work fits within a multi-decade shift in American art in which ceramics and considerations of craft and domestic life rose from relegation to second-class status to recognition as "serious" art. She first received critical attention in the influential and divisive "Bad Girls" exhibition, curated by Marcia Tucker at the New Museum in 1994, where she installed a functional, handmade ceramic bathroom, rendered in the classic blue-and-white style of Delftware. Art in America critic Lilly Wei describes Agee's later work as "the mischievous, wonderfully misbegotten offspring of sculpture, painting, objet d'art, and kitschy souvenir."

Paul Benney is a British artist who rose to international prominence as a contemporary artist whilst living and working in New York in the 1980s and 1990s in the UK as an portraitist.

John Zurier is an American abstract painter, known for his minimal, near-monochrome paintings. His work has shown across the United States as well as in Europe and Japan. He has worked in Reykjavik, Iceland and Berkeley, California. Zurier lives in Berkeley, California.

Erin M. Riley is a Brooklyn-based artist whose work focuses on women and women's issues primarily in hand-woven hand dyed wool tapestries. Riley's work challenges society's comfort level by displaying shocking images including nudity, drugs, violence, self harm, sexuality, and menstruation.

Richard Shaw is an American ceramicist and professor known for his trompe-l'œil style. A term often associated with paintings, referring to the illusion that a two-dimensional surface is three-dimensional. In Shaw's work, it refers to his replication of everyday objects in porcelain. He then glazes these components and groups them in unexpected and even jarring combinations. Interested in how objects can reflect a person or identity, Shaw poses questions regarding the relationship between appearances and reality.

Pamela Helena Wilson is an American artist. She is best known for watercolor drawings and paintings derived from photographs, largely of news events, architectural forms and landscapes. Her journalistic sources frequently portray scenes of natural and human-made calamity and the conflict, devastation and reactions that follow, often involving teeming crowds and demonstrations. Wilson's process and visual editing obscure these events, translating the images into suggestive, new visual experiences with greater urgency, universality and an open-endedness that plays against expectations. In 2013, critic Michelle Grabner wrote, "The luminosity of watercolor on white paper and the alluring atmospheric effects [Wilson] achieves in this medium creates images that are neither photographic or illustrational but seductively abstract and representational."

M. Louise Stanley is an American painter known for irreverent figurative work that combines myth and allegory, satire, autobiography, and social commentary. Writers such as curator Renny Pritikin situate her early-1970s work at the forefront of the "small, but potent" Bad Painting movement, so named for its "disregard for the niceties of conventional figurative painting." Stanley's paintings frequently focus on romantic fantasies and conflicts, social manners and taboos, gender politics, and lampoons of classical myths, portrayed through stylized figures, expressive color, frenetic compositions and slapstick humor. Art historians such as Whitney Chadwick place Stanley within a Bay Area narrative tradition that blended eclectic sources and personal styles in revolt against mid-century modernism; her work includes a feminist critique of contemporary life and art springing from personal experience and her early membership in the Women's Movement. Stanley has been awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship and grants from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation, and National Endowment for the Arts. Her work has been shown at institutions including PS1, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), The New Museum and Long Beach Museum of Art, and belongs to public collections including SFMOMA, San Jose Museum of Art, Oakland Museum, and de Saisset Museum. Stanley lives and works in Emeryville, California.

Olive Madora Ayhens, is an American visual artist. She first gained recognition in California in the 1970s for stylized figurative work, but is most known for the fantastical, dizzying cityscapes, landscapes and interiors, often depicting New York City, that she has painted since the mid-1990s. These works intermingle the urban and pastoral, and inside and outside, employing absurd juxtapositions, improbabilities of scale and vibrant colors, in pointed but playful explorations of the clash between civilization and nature. New York Sun critic David Cohen has described her images as "poised between the lyrical and the apocalyptic. They capture both the poetry and the politics of the densely populated, literally and metaphorically stratified, used and abused city." She is based in Brooklyn, New York.

Judith Simonian is an American artist known for her montage-like paintings and early urban public art. She began her career as a significant participant in an emergent 1980s downtown Los Angeles art scene that spawned street art and performances, galleries and institutions such as Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE) and Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art (LAICA), before moving to New York City in 1985.

Katharine Kuharic is an American artist known for multi-layered representational paintings that combine allegory, humor, social critique, and aspects of Pop and pastoral art. Her art typically employs painstaking brushwork, high-keyed, almost hallucinogenic color, discontinuities of scale, and compositions packed with a profusion of hyper-real detail, figures and associations. She has investigated themes including queer sexual and political identity, American excess and suburban culture, social mores, the body and death. Artist-critic David Humphrey called Kuharic "a visionary misuser" who reconfigures disparate elements into a "Queer Populist Hallucinatory Realism" of socially charged image-sentences that shake out ideologies from "the congealed facts of contemporary culture" and celebrate the possibility of an alternative order.

Katherine Sherwood is an American artist living and working in the San Francisco Bay Area, California who is known for paintings that explore disability, feminism, and healing, and for her teaching and disability rights activism at the Department of Art Practice at the University of California, Berkeley.

Judith Belzer is an American painter based in Berkeley, California. She is known for semi-abstract oils and watercolors depicting invented landscapes in which the natural and built worlds collide and adjoin. These hybrid scenes have been described as dynamic, distanced but expressive, and non-prescriptive—more provocative than overtly critical observations of environmental change. In an Artillery review Barbara Morris wrote, "Belzer explores the edge where the natural world interfaces with the industrialized landscape, emphasizing how rhythms and patterns found in nature are echoed in the structures that man has created … [and] conveying our anxious energy as we struggle for equilibrium in a world permanently altered by our actions."