In mathematics and physics, Laplace's equation is a second-order partial differential equation named after Pierre-Simon Laplace, who first studied its properties. This is often written as or where is the Laplace operator, is the divergence operator, is the gradient operator, and is a twice-differentiable real-valued function. The Laplace operator therefore maps a scalar function to another scalar function.

Surface tension is the tendency of liquid surfaces at rest to shrink into the minimum surface area possible. Surface tension is what allows objects with a higher density than water such as razor blades and insects to float on a water surface without becoming even partly submerged.

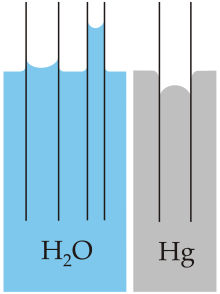

Capillary action is the process of a liquid flowing in a narrow space in opposition to or at least without the assistance of any external forces like gravity.

In physics, Washburn's equation describes capillary flow in a bundle of parallel cylindrical tubes; it is extended with some issues also to imbibition into porous materials. The equation is named after Edward Wight Washburn; also known as Lucas–Washburn equation, considering that Richard Lucas wrote a similar paper three years earlier, or the Bell-Cameron-Lucas-Washburn equation, considering J.M. Bell and F.K. Cameron's discovery of the form of the equation in 1906.

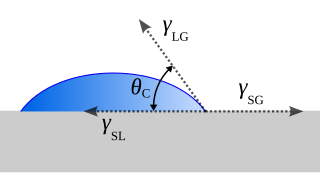

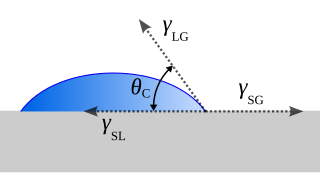

Wetting is the ability of a liquid to displace gas to maintain contact with a solid surface, resulting from intermolecular interactions when the two are brought together. This happens in presence of a gaseous phase or another liquid phase not miscible with the first one. The degree of wetting (wettability) is determined by a force balance between adhesive and cohesive forces. There are two types of wetting: non-reactive wetting and reactive wetting.

The contact angle is the angle between a liquid surface and a solid surface where they meet. More specifically, it is the angle between the surface tangent on the liquid–vapor interface and the tangent on the solid–liquid interface at their intersection. It quantifies the wettability of a solid surface by a liquid via the Young equation.

In atmospheric dynamics, oceanography, asteroseismology and geophysics, the Brunt–Väisälä frequency, or buoyancy frequency, is a measure of the stability of a fluid to vertical displacements such as those caused by convection. More precisely it is the frequency at which a vertically displaced parcel will oscillate within a statically stable environment. It is named after David Brunt and Vilho Väisälä. It can be used as a measure of atmospheric stratification.

In fluid statics, capillary pressure is the pressure between two immiscible fluids in a thin tube, resulting from the interactions of forces between the fluids and solid walls of the tube. Capillary pressure can serve as both an opposing or driving force for fluid transport and is a significant property for research and industrial purposes. It is also observed in natural phenomena.

In physics, spherical multipole moments are the coefficients in a series expansion of a potential that varies inversely with the distance R to a source, i.e., as Examples of such potentials are the electric potential, the magnetic potential and the gravitational potential.

In fluid mechanics, the Cheerios effect is a colloquial name for the phenomenon of floating objects appearing to either attract or repel one another. The example which gives the effect its name is the observation that pieces of breakfast cereal floating on the surface of a bowl will tend to clump together, or appear to stick to the side of the bowl.

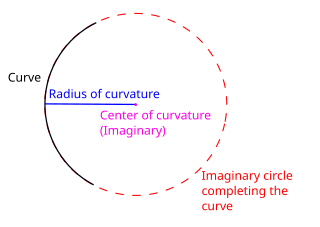

In physics, the Young–Laplace equation is an algebraic equation that describes the capillary pressure difference sustained across the interface between two static fluids, such as water and air, due to the phenomenon of surface tension or wall tension, although use of the latter is only applicable if assuming that the wall is very thin. The Young–Laplace equation relates the pressure difference to the shape of the surface or wall and it is fundamentally important in the study of static capillary surfaces. It is a statement of normal stress balance for static fluids meeting at an interface, where the interface is treated as a surface : where is the Laplace pressure, the pressure difference across the fluid interface, is the surface tension, is the unit normal pointing out of the surface, is the mean curvature, and and are the principal radii of curvature. Note that only normal stress is considered, because a static interface is possible only in the absence of tangential stress.

The capillary length or capillary constant is a length scaling factor that relates gravity and surface tension. It is a fundamental physical property that governs the behavior of menisci, and is found when body forces (gravity) and surface forces are in equilibrium.

In fluid mechanics and mathematics, a capillary surface is a surface that represents the interface between two different fluids. As a consequence of being a surface, a capillary surface has no thickness in slight contrast with most real fluid interfaces.

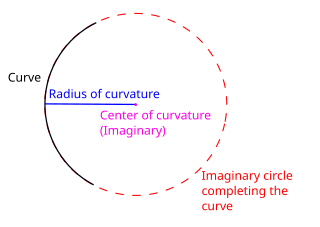

In differential geometry, the radius of curvature, R, is the reciprocal of the curvature. For a curve, it equals the radius of the circular arc which best approximates the curve at that point. For surfaces, the radius of curvature is the radius of a circle that best fits a normal section or combinations thereof.

In mathematics, log-polar coordinates is a coordinate system in two dimensions, where a point is identified by two numbers, one for the logarithm of the distance to a certain point, and one for an angle. Log-polar coordinates are closely connected to polar coordinates, which are usually used to describe domains in the plane with some sort of rotational symmetry. In areas like harmonic and complex analysis, the log-polar coordinates are more canonical than polar coordinates.

In physics, the distorted Schwarzschild metric is the metric of a standard/isolated Schwarzschild spacetime exposed in external fields. In numerical simulation, the Schwarzschild metric can be distorted by almost arbitrary kinds of external energy–momentum distribution. However, in exact analysis, the mature method to distort the standard Schwarzschild metric is restricted to the framework of Weyl metrics.

Elasto-capillarity is the ability of capillary force to deform an elastic material. From the viewpoint of mechanics, elastocapillarity phenomena essentially involve competition between the elastic strain energy in the bulk and the energy on the surfaces/interfaces. In the modeling of these phenomena, some challenging issues are, among others, the exact characterization of energies at the micro scale, the solution of strongly nonlinear problems of structures with large deformation and moving boundary conditions, and instability of either solid structures or droplets/films.The capillary forces are generally negligible in the analysis of macroscopic structures but often play a significant role in many phenomena at small scales.

A capillary bridge is a minimized surface of liquid or membrane created between two rigid bodies of arbitrary shape. Capillary bridges also may form between two liquids. Plateau defined a sequence of capillary shapes known as (1) nodoid with 'neck', (2) catenoid, (3) unduloid with 'neck', (4) cylinder, (5) unduloid with 'haunch' (6) sphere and (7) nodoid with 'haunch'. The presence of capillary bridge, depending on their shapes, can lead to attraction or repulsion between the solid bodies. The simplest cases of them are the axisymmetric ones. We distinguished three important classes of bridging, depending on connected bodies surface shapes:

The rise in core (RIC) method is an alternate reservoir wettability characterization method described by S. Ghedan and C. H. Canbaz in 2014. The method enables estimation of all wetting regions such as strongly water wet, intermediate water, oil wet and strongly oil wet regions in relatively quick and accurate measurements in terms of Contact angle rather than wettability index.

In the theory of capillarity, Bosanquet equation is an improved modification of the simpler Lucas–Washburn theory for the motion of a liquid in a thin capillary tube or a porous material that can be approximated as a large collection of capillaries. In the Lucas–Washburn model, the inertia of the fluid is ignored, leading to the assumption that flow is continuous under constant viscous laminar Poiseuille flow conditions without considering the effects of mass transport undergoing acceleration occurring at the start of flow and at points of changing internal capillary geometry. The Bosanquet equation is a differential equation that is second-order in the time derivative, similar to Newton's Second Law, and therefore takes into account the fluid inertia. Equations of motion, like the Washburn's equation, that attempt to explain a velocity as proportional to a driving force are often described with the term Aristotelian mechanics.