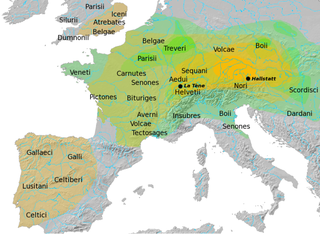

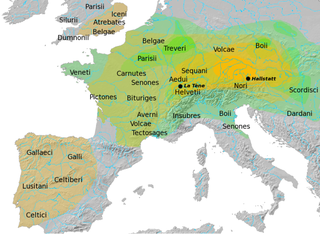

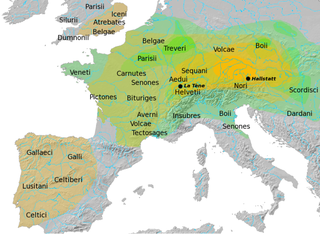

The Celts or Celtic peoples were a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia, identified by their use of Celtic languages and other cultural similarities. Major Celtic groups included the Gauls; the Celtiberians and Gallaeci of Iberia; the Britons, Picts, and Gaels of Britain and Ireland; the Boii; and the Galatians. The relation between ethnicity, language and culture in the Celtic world is unclear and debated; for example over the ways in which the Iron Age people of Britain and Ireland should be called Celts. In current scholarship, 'Celt' primarily refers to 'speakers of Celtic languages' rather than to a single ethnic group.

The La Tène culture was a European Iron Age culture. It developed and flourished during the late Iron Age, succeeding the early Iron Age Hallstatt culture without any definite cultural break, under considerable Mediterranean influence from the Greeks in pre-Roman Gaul, the Etruscans, and the Golasecca culture, but whose artistic style nevertheless did not depend on those Mediterranean influences.

Hallstatt is a small town in the district of Gmunden, in the Austrian state of Upper Austria. Situated between the southwestern shore of Hallstätter See and the steep slopes of the Dachstein massif, the town lies in the Salzkammergut region, on the national road linking Salzburg and Graz.

The Hallstatt culture was the predominant Western and Central European archaeological culture of the Late Bronze Age from the 12th to 8th centuries BC and Early Iron Age Europe from the 8th to 6th centuries BC, developing out of the Urnfield culture of the 12th century BC and followed in much of its area by the La Tène culture. It is commonly associated with Proto-Celtic speaking populations.

Hallein is a historic town in the Austrian state of Salzburg. It is the capital of Hallein district.

Celtic art is associated with the peoples known as Celts; those who spoke the Celtic languages in Europe from pre-history through to the modern period, as well as the art of ancient peoples whose language is uncertain, but have cultural and stylistic similarities with speakers of Celtic languages.

The Oppidum of Manching was a large Celtic proto-urban or city-like settlement at modern-day Manching, near Ingolstadt, in Bavaria, Germany. The Iron Age town was founded in the 3rd century BC and existed until c. 50-30 BC. It reached its largest extent during the late La Tène period, when it had a size of 380 hectares. At that time, 5,000 to 10,000 people lived within its 7.2 km walls. Thus, the Manching oppidum was one of the largest settlements north of the Alps. The ancient name of the site is unknown, but it is assumed that it was the central site of the Celtic Vindelici tribe.

Situla, from the Latin word for bucket or pail, is the term in archaeology and art history for a variety of elaborate bucket-shaped vessels from the Bronze Age to the Middle Ages, usually with a handle at the top. All types may be highly decorated, most characteristically with reliefs in bands or friezes running round the vessel.

The Glauberg is a Celtic hillfort or oppidum in Hesse, Germany consisting of a fortified settlement and several burial mounds, "a princely seat of the late Hallstatt and early La Tène periods." Archaeological discoveries in the 1990s place the site among the most important early Celtic centres in Europe. It provides unprecedented evidence on Celtic burial, sculpture and monumental architecture.

The Golasecca culture was a Late Bronze Age/Early Iron Age culture in northern Italy, whose type-site was excavated at Golasecca in the province of Varese, Lombardy, where, in the area of Monsorino at the beginning of the 19th century, Abbot Giovanni Battista Giani made the first findings of about fifty graves with pottery and metal objects.

The Hochdorf Chieftain's Grave is a richly-furnished Celtic burial chamber near Hochdorf an der Enz in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, dating from 530 BC in the Hallstatt culture period. It was discovered in 1968 by an amateur archaeologist and excavated from 1978 to 1979 by the State Historical site office known as the Baden Wurttenbberg Landesdenkmalamt under the direction of German archeologist Jorg Biel with association from excavation technician Fritz Maurer. By then, the burial mound covering the grave, originally 6 m (20 ft) in height and about 60 m (200 ft) in diameter, had shrunk to about 1 m in height and was hardly discernible due to centuries of erosion and agricultural use.

The Vix Grave is a burial mound near the village of Vix in northern Burgundy. The broader site is a prehistoric Celtic complex from the Late Hallstatt and Early La Tène periods, consisting of a fortified settlement and several burial mounds.

The Hallein Salt Mine, also known as Salzbergwerk Dürrnberg, is an underground salt mine located in the Dürrnberg plateau above Hallein, Austria. The mine has been worked for over 2600 years since the time of the Celtic tribes and earlier. It helped ensure nearby Salzburg would become a powerful trading community. Since World War I, it has served as a mining museum, known for its long wooden slides between levels.

Dürrnberg, also named Bad Dürrnberg, is an Austrian village part of the municipality of Hallein, in Hallein District (Tennengau), Salzburg State. It is the location of the Hallein Salt Mine.

The Basse Yutz Flagons are a pair of Iron Age ceremonial drinking vessels that date from the mid 5th century BCE. Since their discovery in ill-documented circumstances in the 1920s and their subsequent purchase by the British Museum, they have been described as "great masterpieces" that "combine most of the key features of early Celtic Art". They are in many respects very similar to the Dürrnberg Flagon found in Austria.

The Hallstatt Museum is a museum in Hallstatt, Upper Austria, that has an unrivalled collection of discoveries from the local salt mines and from the cemeteries of Iron Age date near to the mines, which have made Hallstatt the type site for the important Hallstatt culture. The museum is close to the Hallstättersee, below the salt mines on the mountainside. The museum, the salt mines, and the Dachstein Ice Cave are designated as an UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Waldalgesheim chariot burial was a 4th-century BC Celtic princely chariot burial site in Waldalgesheim, Germany, discovered in 1869. It has given its name to the "Waldalgesheim Style" of artifacts of the La Tène culture, a more fluid and confident style of decoration than early Celtic art, with Greek and Etruscan influences. The objects from the burial site were dug up by the farmer who found them on his land. The site was not investigated by archaeologists, and has recently been covered by a housing development.

The position of ancient Celtic women in their society cannot be determined with certainty due to the quality of the sources. On the one hand, great female Celts are known from mythology and history; on the other hand, their real status in the male-dominated Celtic tribal society was socially and legally constrained. Yet Celtic women were somewhat better placed in inheritance and marriage law than their Greek and Roman contemporaries.

A beak-spouted ewer is a ewer, jug, pitcher or flagon with a spout formed in the shape of a beak.

The Lavau Grave is princely burial dating to the middle of the 5th century BC, located by the town of Lavau in the Aube department of north-central France.