Related Research Articles

Dolly was a female Finn-Dorset sheep and the first mammal that was cloned from an adult somatic cell. She was cloned by associates of the Roslin Institute in Scotland, using the process of nuclear transfer from a cell taken from a mammary gland. Her cloning proved that a cloned organism could be produced from a mature cell from a specific body part. Contrary to popular belief, she was not the first animal to be cloned.

Human cloning is the creation of a genetically identical copy of a human. The term is generally used to refer to artificial human cloning, which is the reproduction of human cells and tissue. It does not refer to the natural conception and delivery of identical twins. The possibilities of human cloning have raised controversies. These ethical concerns have prompted several nations to pass laws regarding human cloning.

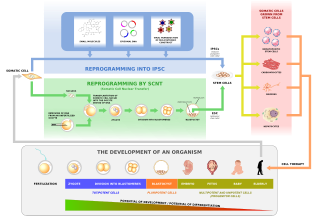

In multicellular organisms, stem cells are undifferentiated or partially differentiated cells that can change into various types of cells and proliferate indefinitely to produce more of the same stem cell. They are the earliest type of cell in a cell lineage. They are found in both embryonic and adult organisms, but they have slightly different properties in each. They are usually distinguished from progenitor cells, which cannot divide indefinitely, and precursor or blast cells, which are usually committed to differentiating into one cell type.

In genetics and developmental biology, somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) is a laboratory strategy for creating a viable embryo from a body cell and an egg cell. The technique consists of taking a denucleated oocyte and implanting a donor nucleus from a somatic (body) cell. It is used in both therapeutic and reproductive cloning. In 1996, Dolly the sheep became famous for being the first successful case of the reproductive cloning of a mammal. In January 2018, a team of scientists in Shanghai announced the successful cloning of two female crab-eating macaques from foetal nuclei.

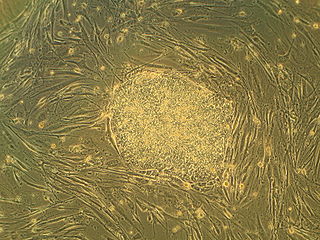

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are pluripotent stem cells derived from the inner cell mass of a blastocyst, an early-stage pre-implantation embryo. Human embryos reach the blastocyst stage 4–5 days post fertilization, at which time they consist of 50–150 cells. Isolating the inner cell mass (embryoblast) using immunosurgery results in destruction of the blastocyst, a process which raises ethical issues, including whether or not embryos at the pre-implantation stage have the same moral considerations as embryos in the post-implantation stage of development.

A stem cell line is a group of stem cells that is cultured in vitro and can be propagated indefinitely. Stem cell lines are derived from either animal or human tissues and come from one of three sources: embryonic stem cells, adult stem cells, or induced pluripotent stem cells. They are commonly used in research and regenerative medicine.

The stem cell controversy concerns the ethics of research involving the development and use of human embryos. Most commonly, this controversy focuses on embryonic stem cells. Not all stem cell research involves human embryos. For example, adult stem cells, amniotic stem cells, and induced pluripotent stem cells do not involve creating, using, or destroying human embryos, and thus are minimally, if at all, controversial. Many less controversial sources of acquiring stem cells include using cells from the umbilical cord, breast milk, and bone marrow, which are not pluripotent.

Rudolf Jaenisch is a Professor of Biology at MIT and a founding member of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research. He is a pioneer of transgenic science, in which an animal’s genetic makeup is altered. Jaenisch has focused on creating genetically modified mice to study cancer, epigenetic reprogramming and neurological diseases.

Robert Lanza is an American medical doctor and scientist, currently Head of Astellas Global Regenerative Medicine, and Chief Scientific Officer of the Astellas Institute for Regenerative Medicine. He is an Adjunct Professor at Wake Forest University School of Medicine.

In bioethics, the ethics of cloning concerns the ethical positions on the practice and possibilities of cloning, especially of humans. While many of these views are religious in origin, some of the questions raised are faced by secular perspectives as well. Perspectives on human cloning are theoretical, as human therapeutic and reproductive cloning are not commercially used; animals are currently cloned in laboratories and in livestock production.

Ann Kiessling is an American reproductive biologist and a researcher in human parthenogenic stem cell research at The Bedford Research Foundation. She was an associate professor in teaching hospitals of Harvard Medical School from 1985 until 2012.

Alan Osborne Trounson is an Australian embryologist with expertise in stem cell research. Trounson was the President of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine between 2007 and 2014, a former Professor of Stem Cell Sciences and the Director of the Monash Immunology and Stem Cell Laboratories at Monash University, and retains the title of emeritus professor.

Shinya Yamanaka is a Japanese stem cell researcher and a Nobel Prize laureate. He is a professor and the director emeritus of Center for iPS Cell Research and Application, Kyoto University; as a senior investigator at the UCSF-affiliated Gladstone Institutes in San Francisco, California; and as a professor of anatomy at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Yamanaka is also a past president of the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR).

Samuel H. Wood is a scientist and fertility specialist. In 2008, he became the first man to clone himself, donating his own DNA via somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) to produce mature human embryos that were his clones.

Stem cell laws are the law rules, and policy governance concerning the sources, research, and uses in treatment of stem cells in humans. These laws have been the source of much controversy and vary significantly by country. In the European Union, stem cell research using the human embryo is permitted in Sweden, Spain, Finland, Belgium, Greece, Britain, Denmark and the Netherlands; however, it is illegal in Germany, Austria, Ireland, Italy, and Portugal. The issue has similarly divided the United States, with several states enforcing a complete ban and others giving support. Elsewhere, Japan, India, Iran, Israel, South Korea, China, and Australia are supportive. However, New Zealand, most of Africa, and most of South America are restrictive.

Stem cell laws and policy in the United States have had a complicated legal and political history.

George Quentin Daley is the Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, Caroline Shields Walker Professor of Medicine, and Professor of Biological Chemistry and Molecular Pharmacology at Harvard Medical School. He was formerly the Robert A. Stranahan Professor of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Director of the Stem Cell Transplantation Program at Boston Children's Hospital, and an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Associate Director of Children's Stem Cell Program, a member of the Executive Committee of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute. He is a past president of the International Society for Stem Cell Research (2007–2008).

Shoukhrat Mitalipov is an American biologist who heads the Center for Embryonic Cell and Gene Therapy at the Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. He is a well known pioneer of many nuclear transplantation studies and was named in 2013 by journal Nature as "the cloning chief". Mitalipov is also a godfather of a gene therapy, known as mitochondrial replacement therapy, that prevents inheritance of mitochondrial diseases. He discovered a new way of creating human stem cells from skin cells.

Yi Zhang is a Chinese-American biochemist who specializes in the fields of epigenetics, chromatin, and developmental reprogramming. He is a Fred Rosen Professor of Pediatrics and professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School, a senior investigator of Program in Cellular and Molecular Medicine at Boston Children's Hospital, and an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. He is also an associate member of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute, as well as the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. He is best known for his discovery of several classes of epigenetic enzymes and the identification of epigenetic barriers of SCNT cloning.

The Hwang affair, or Hwang scandal, or Hwanggate, is a case of scientific misconduct and ethical issues surrounding a South Korean biologist, Hwang Woo-suk, who claimed to have created the first human embryonic stem cells by cloning in 2004. Hwang and his research team at the Seoul National University reported in the journal Science that they successfully developed a somatic cell nuclear transfer method with which they made the stem cells. In 2005, they published again in Science the successful cloning of 11 person-specific stem cells using 185 human eggs. The research was hailed as "a ground-breaking paper" in science. Hwang was elevated as "the pride of Korea", "national hero" [of Korea], and a "supreme scientist", to international praise and fame. Recognitions and honours immediately followed, including South Korea's Presidential Award in Science and Technology, and Time magazine listing him among the "People Who Mattered 2004" and the most influential people "The 2004 Time 100".

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Andrew Rimas (2006-07-03). "Biologist Kevin Eggan: He sees stem cells as a solution". The Boston Globe . Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- 1 2 "B-N native awarded MacArthur 'genius' grant". Associated Press via pantagraph.com. 2006-09-19.

- ↑ "2005 Young Innovators Under 35". Technology Review. 2005. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ↑ https://www.boston.com/news/science/articles/2006/07/03/he_sees_stem_cells_as_a_solution/ - "four sisters and a brother.

- ↑ B-N native awarded MacArthur 'genius' grant

- ↑ Gina Kolata (2004-08-24). "Stem Cells: Promise, in Search of Results". The New York Times . Archived from the original on August 31, 2005. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- ↑ "Kevin Eggan: Steps Towards Stemming Disease". Harvard University Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology News. Archived from the original on 2007-07-06. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- ↑ Matthew Herper (2007-05-24). "P.C. Stem Cells; Kevin Eggan, 32 Cellular Biologist". Forbes . Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- 1 2 Ceci Connolly (2005-08-23). "Stem Cell Advance Muddles Debate; Work May Stall Efforts To Lift Research Limits". The Washington Post . Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- 1 2 3 "Approval granted for Harvard Stem Cell Institute researchers to attempt creation of disease-specific embryonic stem cell lines". The Harvard University Gazette. 2006-06-06. Archived from the original on 2007-07-02. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- ↑ Gareth Cook; Carey Goldberg (2005-08-22). "Harvard scientists advance cell work; technique doesn't destroy embryos". The Boston Globe . Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- 1 2 Elisabeth Eaves; Michael Noer (2007-05-24). "The Revolutionaries". Forbes . Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- 1 2 Erika Check (2004-09-07). "Stem-cell research: The rocky road to success Tackling the legal and ethical minefield associated with human embryonic stem-cell research is not for the faint-hearted". Nature . 437 (7056): 185–186. doi: 10.1038/437185a . PMID 16148905. S2CID 4391808.

- ↑ Matthew Helper (2005-08-23). "Turning Skin Into Stem Cells". Forbes . Archived from the original on January 14, 2006. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- ↑ "Kevin Eggan Wins Harold M. Weintraub Grad Student Award". Archived from the original on 2006-09-01. Retrieved 2007-09-02.

- ↑ Marissa Newhall (2005-09-13). "'Brilliant' minds honored". USA Today . Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- ↑ "Feel the heat!". People Magazine. November 27, 2006. Archived from the original on October 30, 2008.