Kashrut is a set of dietary laws dealing with the foods that Jewish people are permitted to eat and how those foods must be prepared according to Jewish law. Food that may be consumed is deemed kosher, from the Ashkenazi pronunciation of the term that in Sephardi or Modern Hebrew is pronounced kashér, meaning "fit". Food that may not be consumed, however, is deemed treif, also spelled treyf. In case of objects the opposite of kosher is pasúl.

Herem is the highest ecclesiastical censure in the Jewish community. It is the total exclusion of a person from the Jewish community. It is a form of shunning and is similar to vitandus "excommunication" in the Catholic Church. Cognate terms in other Semitic languages include the Arabic terms ḥarām "forbidden, taboo, off-limits, or immoral" and haram "set apart, sanctuary", and the Ge'ez word ʿirm "accursed".

Exsanguination is the loss of blood from the circulatory system of a vertebrate, usually leading to death. The word comes from the Latin 'sanguis', meaning blood, and the prefix 'ex-', meaning 'out of'.

A hechsher or hekhsher is a rabbinical product certification, qualifying items that conform to the requirements of Jewish religious law.

A mashgiach or mashgicha is a Jew who supervises the kashrut status of a kosher establishment. Mashgichim may supervise any type of food service establishment, including slaughterhouses, food manufacturers, hotels, caterers, nursing homes, restaurants, butchers, groceries, or cooperatives. Mashgichim usually work as on-site supervisors and inspectors, representing a kosher certification agency or a local rabbi, who actually makes the policy decisions for what is or is not acceptably kosher. Sometimes certifying rabbis act as their own mashgichim; such is the case in many small communities.

In some religions, an unclean animal is an animal whose consumption or handling is taboo. According to these religions, persons who handle such animals may need to ritually purify themselves to get rid of their uncleanliness.

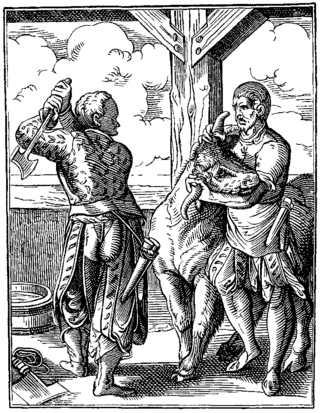

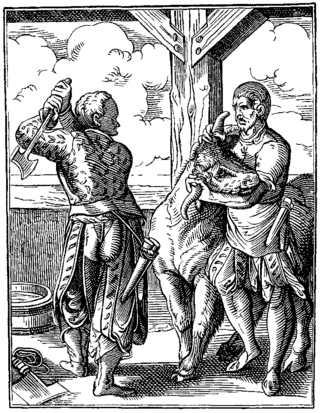

In Judaism, shechita is ritual slaughtering of certain mammals and birds for food according to kashrut. One who practices this, a kosher butcher is called a shochet.

Kosher foods are foods that conform to the Jewish dietary regulations of kashrut. The laws of kashrut apply to food derived from living creatures and kosher foods are restricted to certain types of mammals, birds and fish meeting specific criteria; the flesh of any animals that do not meet these criteria is forbidden by the dietary laws. Furthermore, kosher mammals and birds must be slaughtered according to a process known as shechita and their blood may never be consumed and must be removed from the meat by a process of salting and soaking in water for the meat to be permissible for use. All plant-based products, including fruits, vegetables, grains, herbs and spices, are intrinsically kosher, although certain produce grown in the Land of Israel is subjected to other requirements, such as tithing, before it may be consumed.

Kapparot is a customary atonement ritual practiced by some Orthodox Jews on the eve of Yom Kippur. This is a practice in which either money is waved over a person's head and then donated to charity, or else a chicken is waved over the head and then slaughtered in accordance with halachic rules and donated to the hungry.

The killing of animals is animal euthanasia, animal sacrifice, animal slaughter, hunting, blood sports, roadkill or self-defense.

Hullin or Chullin is the third tractate of the Mishnah in the Order of Kodashim and deals with the laws of ritual slaughter of animals and birds for meat in ordinary or non-consecrated use, and with the Jewish dietary laws in general, such as the laws governing the prohibition of mixing of meat and dairy.

In Islamic law, dhabihah, also spelled zabiha, is the prescribed method of slaughter for halal animals. It consists of a swift, deep incision to the throat with a very sharp knife, cutting the wind pipe, jugular veins and carotid arteries on both sides but leaving the spinal cord intact. The butcher is also required to call upon the name of Allah individually for each animal.

The Islamic dietary laws (halal) and the Jewish dietary laws are both quite detailed, and contain both points of similarity and discord. Both are the dietary laws and described in distinct religious texts: an explanation of the Islamic code of law found in the Quran and Sunnah and the Jewish code of laws found in the Torah, Talmud and Shulchan Aruch.

The legal aspects of ritual slaughter include the regulation of slaughterhouses, butchers, and religious personnel involved with traditional shechita (Jewish) and dhabiha (Islamic). Regulations also may extend to butchery products sold in accordance with kashrut and halal religious law. Governments regulate ritual slaughter, primarily through legislation and administrative law. In addition, compliance with oversight of ritual slaughter is monitored by governmental agencies and, on occasion, contested in litigation.

Animal slaughter is the killing of animals, usually referring to killing domestic livestock. It is estimated that each year, 80 billion land animals are slaughtered for food. Most animals are slaughtered for food; however, they may also be slaughtered for other reasons such as for harvesting of pelts, being diseased and unsuitable for consumption, or being surplus for maintaining a breeding stock. Slaughter typically involves some initial cutting, opening the major body cavities to remove the entrails and offal but usually leaving the carcass in one piece. Such dressing can be done by hunters in the field or in a slaughterhouse. Later, the carcass is usually butchered into smaller cuts.

Ritual slaughter is the practice of slaughtering livestock for meat in the context of a ritual. Ritual slaughter involves a prescribed practice of slaughtering an animal for food production purposes.

The gift of the foreleg, cheeks and maw of a kosher-slaughtered animal to a kohen is a positive commandment in the Hebrew Bible. The Shulchan Aruch rules that after the slaughter of animal by a shochet, the shochet is required to separate the cuts of the foreleg, cheek and maw and give them to a kohen freely, without the kohen paying or performing any service.

Tza'ar ba'alei chayim, literally "suffering of living creatures", is a Jewish commandment which bans causing animals unnecessary suffering. This concept is not clearly enunciated in the written Torah, but was accepted by the Talmud as being a biblical mandate. It is linked in the Talmud from the biblical law requiring people to assist in unloading burdens from animals.

Jewish vegetarianism is a commitment to vegetarianism that is connected to Judaism, Jewish ethics or Jewish identity. Jewish vegetarians often cite Jewish principles regarding animal welfare, environmental ethics, moral character, and health as reasons for adopting a vegetarian or vegan diet.

Shlomo Zev Zweigenhaft was a rabbi who was Rosh Hashochtim of Poland before the Holocaust. After the Holocaust he was Chief Rabbi of Hanover and Lower Saxony. After emigrating to the United States he was a Rav Hamachshir and was described as the "foremost authority on shechita".