Jean Désiré Gustave Courbet was a French painter who led the Realism movement in 19th-century French painting. Committed to painting only what he could see, he rejected academic convention and the Romanticism of the previous generation of visual artists. His independence set an example that was important to later artists, such as the Impressionists and the Cubists. Courbet occupies an important place in 19th-century French painting as an innovator and as an artist willing to make bold social statements through his work.

Alexandre Cabanel was a French painter. He painted historical, classical and religious subjects in the academic style. He was also well known as a portrait painter. He was Napoleon III's preferred painter and, with Gérôme and Meissonier, was one of "the three most successful artists of the Second Empire."

Events from the year 1854 in art.

The Painter's Studio is an 1855 oil-on-canvas painting by Gustave Courbet. It is located in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, France.

Alfred Bruyas was an art collector and a personal friend of many important artists of his time, among them Gustave Courbet and Alexandre Cabanel. He donated his collection to the Musée Fabre, in Montpellier.

The Musée Fabre is a museum in the southern French city of Montpellier, capital of the Hérault département.

Julien Vallou de Villeneuve was a French painter, lithographer and photographer.

Auguste-Barthélemy Glaize (1807–1893) was a French Romantic painter of history paintings and genre paintings.

Nicolas François Octave Tassaert was a French painter of portraits and genre, religious, historical and allegorical paintings, as well as a lithographer and engraver. His genre pieces evoked the miserable life of the downtrodden in Paris and included a number of scenes of suicide. He further created sensuous images of women and erotic scenes. He was later in life active as a writer and poet. He was the grandson of the Flemish sculptor Jean-Pierre-Antoine Tassaert.

A Burial at Ornans is a painting of 1849–50 by Gustave Courbet. It is widely regarded as a major turning point in 19th-century French art. The painting records a funeral in Courbet's birthplace, the small town of Ornans. It treats an ordinary, provincial funeral with frank realism, and on the grand scale traditionally reserved for the heroic or religious scenes of history painting. Its exhibition at the 1850–51 Paris Salon created an "explosive reaction" and brought Courbet instant fame. It is currently displayed at the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, France

Scène d'été, Summer Scene, or The Bathers is an oil-on-canvas painting by the French artist Frédéric Bazille from 1869. It is now in the Fogg Art Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The Impressionist painting depicts young men dressed in swimsuits having a leisurely day along the banks of the Lez river near Montpellier. Bazille composed the painting by first drawing the human figures in his Paris studio and then transporting the drawings to the outdoor setting. Like his earlier painting Réunion de famille (1867), Scène d'été captured friends and family members in the outdoors. Scène d'été was exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1870.

Bottle, Glass, Fork is an oil on canvas painting by Pablo Picasso (1881–1973). It was painted in the spring of 1912, at the height of the development of Analytic Cubism. Bottle, Glass, Fork is one of the best representations of the point in Picasso's career when his Cubist painting reached almost full abstraction. The analytic phase of Cubism was an original art movement developed by Picasso and his contemporary Georges Braque (1882–1963) and lasted from 1908-1912. Like Bottle, Glass, Fork, the paintings of this movement are characterized by the limited use of color, and a complex, elegant composition of small, fragmented, tightly interwoven planes within an all-over composition of broader planes. While the figures in Bottle, Glass, Fork can be difficult to discern, the objects do emerge after careful study of the painting. The painting is displayed in the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Le ruisseau noir (The Black Stream) (also known in En. as Stream in a Ravine) is an oil-on-canvas landscape painted in 1865 by the French artist Gustave Courbet. It is currently held and exhibited at the Musée d'Orsay in Paris.

Realism was an artistic movement that emerged in France in the 1840s, around the 1848 Revolution. Realists rejected Romanticism, which had dominated French literature and art since the early 19th century. Realism revolted against the exotic subject matter and the exaggerated emotionalism and drama of the Romantic movement. Instead, it sought to portray real and typical contemporary people and situations with truth and accuracy. It did not avoid unpleasant or sordid aspects of life. The movement aimed to focus on unidealized subjects and events that were previously rejected in art work. Realist works depicted people of all social classes in situations that arise in ordinary life, and often reflected the changes brought by the Industrial and Commercial Revolutions. Realism was primarily concerned with how things appeared to the eye, rather than containing ideal representations of the world. The popularity of such "realistic" works grew with the introduction of photography—a new visual source that created a desire for people to produce representations which look objectively real.

The Bathers is an oil-on-canvas painting by the French artist Gustave Courbet, first exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1853, where it caused a major scandal. It was unanimously attacked by art critics for the large nude woman at its centre and the sketchy landscape background, both against official artistic canons. It was bought for 3000 francs by Courbet's future friend Alfred Bruyas, an art collector – this acquisition allowed the artist to become financially and artistically independent. It is signed and dated in the bottom right hand corner on a small rock. It has been in the musée Fabre in Montpellier since 1868.

The Romans in their Decadence is a painting by the French artist Thomas Couture, depicting the Roman decadence. It debuted as the most highly acclaimed work of the Paris Salon of 1847, a year before the 1848 Revolution which toppled the July Monarchy. Reminiscent of the style of Raphael, it is typical of the French 'classic' style between 1850 and 1900 today analyzed within the wider current of academic art.

The Seaside at Palavas 1854 is an oil on canvas painting by the French artist Gustave Courbet. It depicts a solitary figure standing on the coast facing the immensity of the sea.

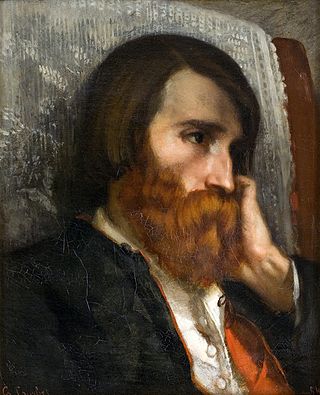

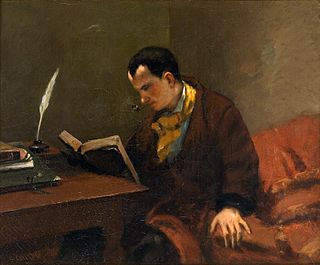

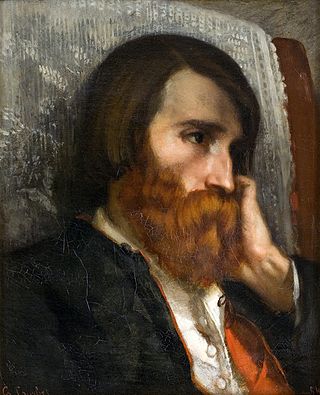

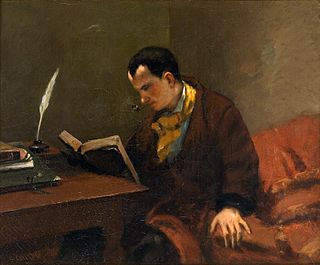

Portrait of Charles Baudelaire is an oil-on-canvas portrait of the poet Charles Baudelaire by the French painter Gustave Courbet. It was painted in 1848 or early 1849, at a time when the poet and the painter had established a friendship.

Young Ladies of the Village or The Village Maids is an 1852 oil-on-canvas painting by the French artist Gustave Courbet, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York. It is signed bottom left "G. Courbet".

Le Désespéré is an oil-on-canvas self-portrait by Gustave Courbet, produced from 1843 to 1845, during his stay in Paris. It depicts Courbet as a young man staring in front of him with wide eyes, grasping his hair in desperation. It is now in the private collection of the Conseil Investissement Art BNP Paribas but was displayed in the Musée d'Orsay's 2007 Courbet exhibition.