Biopolymers are polymers produced by living organisms; in other words, they are polymeric biomolecules. Biopolymers contain monomeric units that are covalently bonded to form larger structures. There are three main classes of biopolymers, classified according to the monomeric units used and the structure of the biopolymer formed: polynucleotides, which are long polymers composed of 13 or more nucleotide monomers; polypeptides, which are short polymers of amino acids; and polysaccharides, which are often linear bonded polymeric carbohydrate structures. Other examples of biopolymers include rubber, suberin, melanin and lignin.

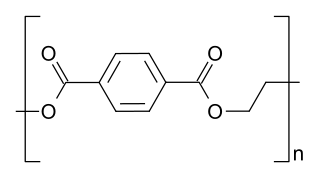

Condensation polymers are any kind of polymers formed through a condensation reaction—where molecules join together—losing small molecules as byproducts such as water or methanol. Condensation polymers are formed by polycondensation, when the polymer is formed by condensation reactions between species of all degrees of polymerization, or by condensative chain polymerization, when the polymer is formed by sequential addition of monomers to an active site in a chain reaction. The main alternative forms of polymerization are chain polymerization and polyaddition, both of which give addition polymers.

A monomer is a molecule that "can undergo polymerization thereby contributing constitutional units to the essential structure of a macromolecule". Large numbers of monomers combine to form polymers in a process called polymerization.

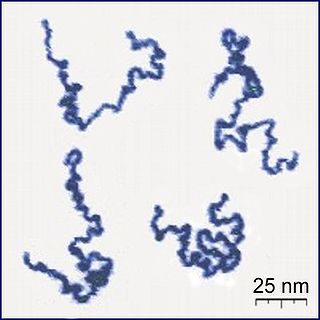

A polymer is a large molecule, or macromolecule, composed of many repeated subunits. Due to their broad range of properties, both synthetic and natural polymers play essential and ubiquitous roles in everyday life. Polymers range from familiar synthetic plastics such as polystyrene to natural biopolymers such as DNA and proteins that are fundamental to biological structure and function. Polymers, both natural and synthetic, are created via polymerization of many small molecules, known as monomers. Their consequently large molecular mass relative to small molecule compounds produces unique physical properties, including toughness, viscoelasticity, and a tendency to form glasses and semicrystalline structures rather than crystals. The terms polymer and resin are often synonymous with plastic.

In polymer chemistry, polymerization is a process of reacting monomer molecules together in a chemical reaction to form polymer chains or three-dimensional networks. There are many forms of polymerization and different systems exist to categorize them.

Catabolism is the set of metabolic pathways that breaks down molecules into smaller units that are either oxidized to release energy or used in other anabolic reactions. Catabolism breaks down large molecules into smaller units. Catabolism is the breaking-down aspect of metabolism, whereas anabolism is the building-up aspect.

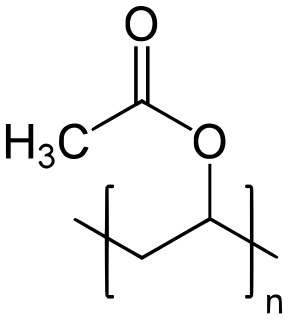

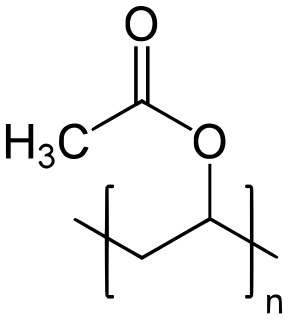

Poly(vinyl acetate) (PVA, PVAc, poly(ethenyl ethanoate): best known as wood glue, white glue, carpenter's glue, school glue, Elmer's glue in the US, or PVA glue) is an aliphatic rubbery synthetic polymer with the formula (C4H6O2)n. It belongs to the polyvinyl esters family, with the general formula -[RCOOCHCH2]-. It is a type of thermoplastic. There is considerable confusion between the glue as purchased, an aqueous emulsion of mostly vinyl acetate monomer, and the subsequent dried and polymerized PVAc that is the true thermoplastic polymer.

A dimer is an oligomer consisting of two monomers joined by bonds that can be either strong or weak, covalent or intermolecular. The term homodimer is used when the two molecules are identical and heterodimer when they are not. The reverse of dimerisation is often called dissociation. When two oppositely charged ions associate into dimers, they are referred to as Bjerrum pairs.

A polyamide is a macromolecule with repeating units linked by amide bonds.

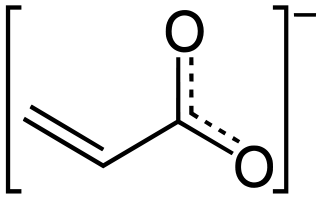

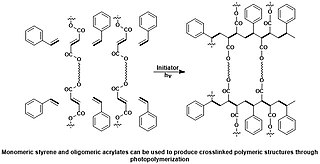

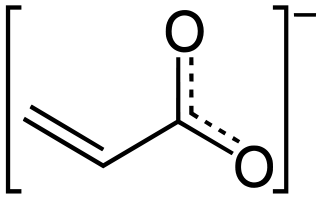

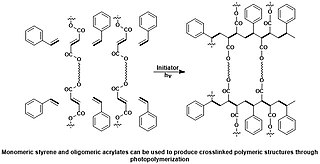

Acrylates (IUPAC: prop-2-enoates) are the salts, esters, and conjugate bases of acrylic acid and its derivatives. The acrylate ion is the anion CH2=CHCOO−. Often acrylate refers to esters of acrylic acid, the most common member being methyl acrylate. Acrylates contain vinyl groups directly attached to the carbonyl carbon. These monomers are of interest because they are bifunctional: the vinyl group is susceptible to polymerization and the carboxylate group carries myriad functionality. Modified acrylates are also numerous, include methacrylates (CH2=C(CH3)CO2R) and cyanoacrylates (CH2=C(CN)CO2R).

Polyglycolide or poly(glycolic acid) (PGA), also spelled as polyglycolic acid, is a biodegradable, thermoplastic polymer and the simplest linear, aliphatic polyester. It can be prepared starting from glycolic acid by means of polycondensation or ring-opening polymerization. PGA has been known since 1954 as a tough fiber-forming polymer. Owing to its hydrolytic instability, however, its use has initially been limited. Currently polyglycolide and its copolymers are widely used as a material for the synthesis of absorbable sutures and are being evaluated in the biomedical field.

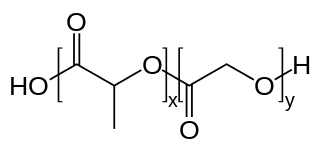

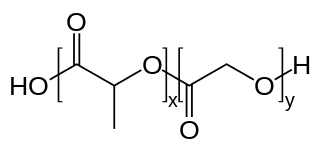

PLGA, PLG, or poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) is a copolymer which is used in a host of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved therapeutic devices, owing to its biodegradability and biocompatibility. PLGA is synthesized by means of ring-opening co-polymerization of two different monomers, the cyclic dimers (1,4-dioxane-2,5-diones) of glycolic acid and lactic acid. Polymers can be synthesized as either random or block copolymers thereby imparting additional polymer properties. Common catalysts used in the preparation of this polymer include tin(II) 2-ethylhexanoate, tin(II) alkoxides, or aluminum isopropoxide. During polymerization, successive monomeric units are linked together in PLGA by ester linkages, thus yielding a linear, aliphatic polyester as a product.

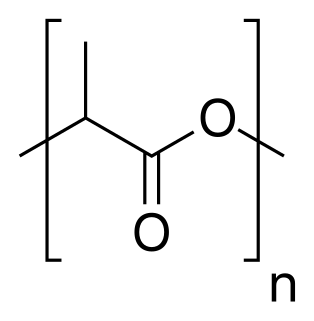

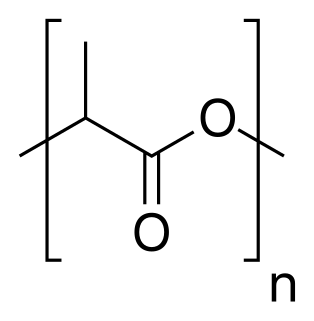

Polylactic acid or polylactide (PLA) is a thermoplastic aliphatic polyester derived from renewable biomass, typically from fermented plant starch such as from corn, cassava, sugarcane or sugar beet pulp. In 2010, PLA had the second highest consumption volume of any bioplastic of the world.

Acidogenesis is the second stage in the four stages of anaerobic digestion:

Nitrile rubber, also known as NBR, Buna-N, and acrylonitrile butadiene rubber, is a synthetic rubber copolymer of acrylonitrile (ACN) and butadiene. Trade names include Perbunan, Nipol, Krynac and Europrene.

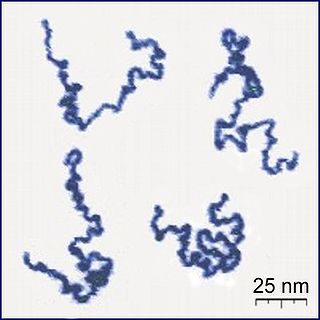

Reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer or RAFT polymerization is one of several kinds of reversible-deactivation radical polymerization. It makes use of a chain transfer agent in the form of a thiocarbonylthio compound to afford control over the generated molecular weight and polydispersity during a free-radical polymerization. Discovered at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) of Australia in 1998, RAFT polymerization is one of several living or controlled radical polymerization techniques, others being atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) and nitroxide-mediated polymerization (NMP), etc. RAFT polymerization uses thiocarbonylthio compounds, such as dithioesters, thiocarbamates, and xanthates, to mediate the polymerization via a reversible chain-transfer process. As with other controlled radical polymerization techniques, RAFT polymerizations can be performed with conditions to favor low dispersity and a pre-chosen molecular weight. RAFT polymerization can be used to design polymers of complex architectures, such as linear block copolymers, comb-like, star, brush polymers, dendrimers and cross-linked networks.

A photopolymer or light-activated resin is a polymer that changes its properties when exposed to light, often in the ultraviolet or visible region of the electromagnetic spectrum. These changes are often manifested structurally, for example hardening of the material occurs as a result of cross-linking when exposed to light. An example is shown below depicting a mixture of monomers, oligomers, and photoinitiators that conform into a hardened polymeric material through a process called curing. A wide variety of technologically useful applications rely on photopolymers, for example some enamels and varnishes depend on photopolymer formulation for proper hardening upon exposure to light. In some instances, an enamel can cure in a fraction of a second when exposed to light, as opposed to thermally cured enamels which can require half an hour or longer. Curable materials are widely used for medical, printing, and photoresist technologies.

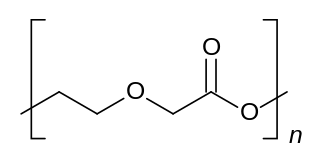

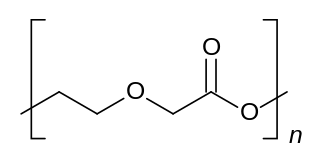

Polydioxanone or poly-p-dioxanone is a colorless, crystalline, biodegradable synthetic polymer.

The term pre-polymer refers to a monomer or system of monomers that have been reacted to an intermediate molecular mass state. This material is capable of further polymerization by reactive groups to a fully cured high molecular weight state. As such, mixtures of reactive polymers with un-reacted monomers may also be referred to as pre-polymers. The term “pre-polymer” and “polymer precursor” may be interchanged.