Athanasius Kircher was a German Jesuit scholar and polymath who published around 40 major works of comparative religion, geology, and medicine. Kircher has been compared to fellow Jesuit Roger Joseph Boscovich and to Leonardo da Vinci for his vast range of interests, and has been honoured with the title "Master of a Hundred Arts". He taught for more than 40 years at the Roman College, where he set up a wunderkammer. A resurgence of interest in Kircher has occurred within the scholarly community in recent decades.

Raphael Fabretti was an Italian antiquarian.

Oedipus Aegyptiacus is Athanasius Kircher's supreme work of Egyptology.

The Villa d'Este is a 16th-century villa in Tivoli, near Rome, famous for its terraced hillside Italian Renaissance garden and especially for its profusion of fountains. It is now an Italian state museum, and is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Palestrina is a modern Italian city and comune (municipality) with a population of about 22,000, in Lazio, about 35 kilometres east of Rome. It is connected to the latter by the Via Prenestina. It is built upon the ruins of the ancient city of Praeneste.

Fortuna is the goddess of fortune and the personification of luck in Roman religion who, largely thanks to the Late Antique author Boethius, remained popular through the Middle Ages until at least the Renaissance. The blindfolded depiction of her is still an important figure in many aspects of today's Italian culture, where the dichotomy fortuna / sfortuna plays a prominent role in everyday social life, also represented by the very common refrain "La [dea] fortuna è cieca".

Egypt has had a legendary image in the Western world through the Greek and Hebrew traditions. Egypt was already ancient to outsiders, and the idea of Egypt has continued to be at least as influential in the history of ideas as the actual historical Egypt itself. All Egyptian culture was transmitted to Roman and post-Roman European culture through the lens of Hellenistic conceptions of it, until the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphics by Jean-François Champollion in the 1820s rendered Egyptian texts legible, finally enabling an understanding of Egypt as the Egyptians themselves understood it.

The Roman Campagna is a low-lying area surrounding Rome in the Lazio region of central Italy, with an area of approximately 2,100 square kilometres (810 sq mi).

The National Roman Museum is a museum, with several branches in separate buildings throughout the city of Rome, Italy. It shows exhibits from the pre- and early history of Rome, with a focus on archaeological findings from the period of Ancient Rome.

Latium is the region of central western Italy in which the city of Rome was founded and grew to be the capital city of the Roman Empire.

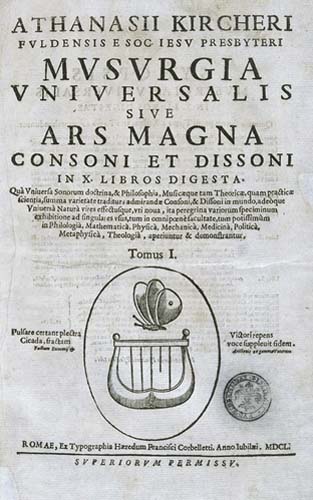

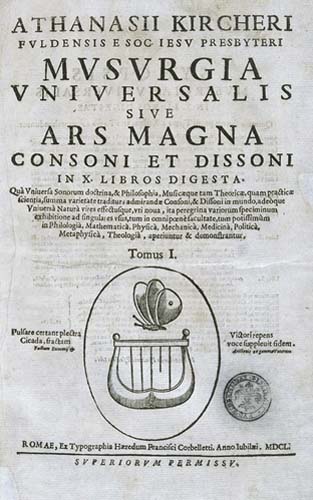

Musurgia Universalis, sive Ars Magna Consoni et Dissoni is a 1650 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was printed in Rome by Ludovico Grignani and dedicated to Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria. It was a compendium of ancient and contemporary thinking about music, its production and its effects. It explored, in particular, the relationship between the mathematical properties of music with health and rhetoric. The work complements two of Kircher's other books: Magnes sive de Arte Magnetica had set out the secret underlying coherence of the universe and Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae had explored the ways of knowledge and enlightenment. What Musurgia Universalis contained, through its exploration of dissonance within harmony, was an explanation of the presence of evil in the world.

Francesco (de') Ficoroni (1664–1747) was an Italian connoisseur and antiquarian in Rome closely involved with the antiquities trade. He was the author of numerous publications on ancient Roman sculpture and antiquities, guides to the monuments of Rome and the city's ancient topography, and on Italian theatre and theatrical masks, among other subjects. For his antiquarian works he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of London. A major segment of his potential audience, both for his publications and for the objects from his perpetually changing collection, was composed of British milordi on their Grand Tours. His complementary volumes on ancient and modern Rome (1744) remained in print long after his death: Thomas Jefferson purchased both volumes while he was abroad in 1785-89.

China Illustrata is the 1667 published book written by the Jesuit Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680) that compiles the 17th-century European knowledge on the Chinese Empire and its neighboring countries. The original Latin title is Athanasii Kircheri e Soc. Jesu China monumentis, qua sacris qua profanis, nec non variis Naturae et artis spectaculis, aliarumque rerum memorabilium argumentis illustrata, auspiciis Leopoldi primi, Roman. Imper. Semper augusti Munificentissimi Mecaenatis.

The sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia was an ancient Roman, religious complex in Praeneste founded in 204 BC by Publius Sempronius Tuditanus. The temple within the sanctuary was dedicated to the goddess Fortuna Primigenia, or Fortune of the First Born. Parents brought their newly-born first child to the temple in order to improve its likelihood of surviving infancy and perpetuating the gens.

Turris Babel was a 1679 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was the last of his books published during his lifetime. Together with his earlier work Arca Noë, it represents Kircher's endeavour to show how modern science supported the Biblical narrative in the Book of Genesis. The work was also a broad synthesis of many of Kircher's ideas on architecture, language and religion. The book was dedicated to the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I and printed in Amsterdam by the cartographer and bookseller Johannes van Waesbergen.

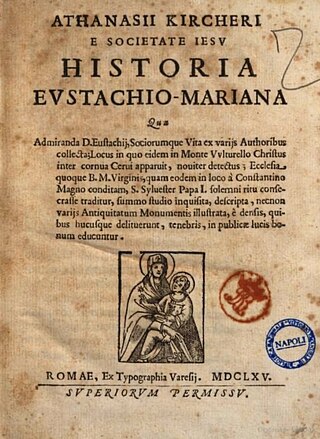

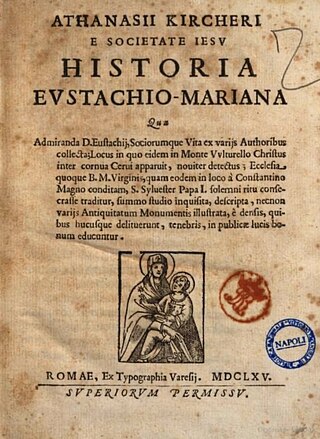

Historia Eustachio Mariana is a 1665 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It describes his chance discovery of a ruined shrine of the Virgin Mary at Mentorella, the site where tradition held that the Roman martyr Saint Eustace had experienced conversion to Christianity. The book was dedicated to Giovanni Nicola, abbot of the monastery at Vulturalla, and a member of the family of the counts of Poli. It was intended to help raise funds for the restoration of the chapel, and it was Kircher's first topographical work.

Scrutinium Physico-Medicum Contagiosae Luis, Quae Pestis Dicitur is a 1658 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher, containing his observations and theories about the bubonic plague that struck Rome in the summer of 1656. Kircher was the first person to view infected blood through a microscope, and his observations are described in the book. The work was printed on the presses of Vitale Mascardi and dedicated to Pope Alexander VII.

Obeliscus Pamphilius is a 1650 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was published in Rome by Ludovico Grignani and dedicated to Pope Innocent X in his jubilee year. The subject of the work was Kircher's attempt to translate the hieroglyphs on the sides of an obelisk erected in the Piazza Navona.

Magnes sive de Arte Magnetica is a 1641 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was dedicated to Emperor Ferdinand III and printed in Rome by Hermann Scheuss. It developed the ideas set out in his earlier Ars Magnesia and argued that the universe is governed by universal physical forces of attraction and repulsion. These were, as described in the motto in the book's first illustration, 'hidden nodes' of connection. The force that drew things together in the physical world was, he argued, the same force that drew people's souls towards God. The work is divided into three books: 1.De natura et facultatibus magnetis, 2.Magnes applicatus, 3.Mundus sive catena magnetica. It is noted for the first use of the term 'electromagnetism'.

Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae is a 1646 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was dedicated to Ferdinand IV, King of the Romans and published in Rome by Lodovico Grignani. A second edition was published in Amsterdam in 1671 by Johann Jansson. Ars Magna was the first description published in Europe of the illumination and projection of images. The book contains the first printed illustration of Saturn and the 1671 edition also contained a description of the magic lantern.