A plaintiff is the party who initiates a lawsuit before a court. By doing so, the plaintiff seeks a legal remedy. If this search is successful, the court will issue judgment in favor of the plaintiff and make the appropriate court order. "Plaintiff" is the term used in civil cases in most English-speaking jurisdictions, the notable exceptions being England and Wales, where a plaintiff has, since the introduction of the Civil Procedure Rules in 1999, been known as a "claimant" and Scotland, where the party has always been known as the "pursuer". In criminal cases, the prosecutor brings the case against the defendant, but the key complaining party is often called the "complainant".

A tort is a civil wrong, other than breach of contract, that causes a claimant to suffer loss or harm, resulting in legal liability for the person who commits the tortious act. Tort law can be contrasted with criminal law, which deals with criminal wrongs that are punishable by the state. While criminal law aims to punish individuals who commit crimes, tort law aims to compensate individuals who suffer harm as a result of the actions of others. Some wrongful acts, such as assault and battery, can result in both a civil lawsuit and a criminal prosecution in countries where the civil and criminal legal systems are separate. Tort law may also be contrasted with contract law, which provides civil remedies after breach of a duty that arises from a contract. Obligations in both tort and criminal law are more fundamental and are imposed regardless of whether the parties have a contract.

Civil procedure is the body of law that sets out the rules and regulations along with some standards that courts follow when adjudicating civil lawsuits. These rules govern how a lawsuit or case may be commenced; what kind of service of process is required; the types of pleadings or statements of case, motions or applications, and orders allowed in civil cases; the timing and manner of depositions and discovery or disclosure; the conduct of trials; the process for judgment; the process for post-trial procedures; various available remedies; and how the courts and clerks must function.

Delict is a term in civil and mixed law jurisdictions whose exact meaning varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction but is always centered on the notion of wrongful conduct.

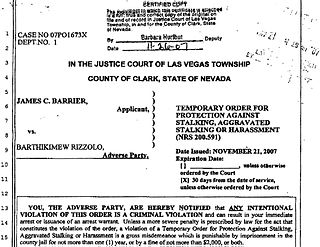

A restraining order or protective order is an order used by a court to protect a person in a situation often involving alleged domestic violence, child abuse, assault, harassment, stalking, or sexual assault.

Breach of the peace or disturbing the peace is a legal term used in constitutional law in English-speaking countries and in a public order sense in the United Kingdom. It is a form of disorderly conduct.

A sheriff court is the principal local civil and criminal court in Scotland, with exclusive jurisdiction over all civil cases with a monetary value up to £100,000, and with the jurisdiction to hear any criminal case except treason, murder, and rape, which are in the exclusive jurisdiction of the High Court of Justiciary. Though the sheriff courts have concurrent jurisdiction with the High Court over armed robbery, drug trafficking, and sexual offences involving children, the vast majority of these cases are heard by the High Court. Each court serves a sheriff court district within one of the six sheriffdoms of Scotland. Each sheriff court is presided over by a sheriff, who is a legally qualified judge, and part of the judiciary of Scotland.

The Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service is the independent public prosecution service for Scotland, and is a Ministerial Department of the Scottish Government. The department is headed by His Majesty's Lord Advocate, who under the Scottish legal system is responsible for prosecution, along with the sheriffdom procurators fiscal. In Scotland, virtually all prosecution of criminal offences is undertaken by the Crown. Private prosecutions are extremely rare.

Delict in Scots law is the area of law concerned with those civil wrongs which are actionable before the Scottish courts. The Scots use of the term 'delict' is consistent with the jurisdiction's connection with Civilian jurisprudence; Scots private law has a 'mixed' character, blending together elements borrowed from Civil law and Common law, as well as indigenous Scottish developments. The term tort law, or 'law of torts', is used in Anglo-American jurisdictions to describe the area of law in those systems. Unlike in a system of torts, the Scots law of delict operates on broad principles of liability for wrongdoing: 'there is no such thing as an exhaustive list of named delicts in the law of Scotland. If the conduct complained of appears to be wrongful, the law of Scotland will afford a remedy even if there has not been any previous instance of a remedy being given in similar circumstances'. While some terms such as assault and defamation are used in systems of tort law, their technical meanings differ in Scottish delict.

The courts of Scotland are responsible for administration of justice in Scotland, under statutory, common law and equitable provisions within Scots law. The courts are presided over by the judiciary of Scotland, who are the various judicial office holders responsible for issuing judgments, ensuring fair trials, and deciding on sentencing. The Court of Session is the supreme civil court of Scotland, subject to appeals to the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, and the High Court of Justiciary is the supreme criminal court, which is only subject to the authority of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom on devolution issues and human rights compatibility issues.

A procurator fiscal, sometimes called PF or fiscal, is a public prosecutor in Scotland, who has the power to impose fiscal fines. They investigate all sudden and suspicious deaths in Scotland, conduct fatal accident inquiries and handle criminal complaints against the police. They also receive reports from specialist reporting agencies such as His Majesty's Revenue and Customs.

Precognition in Scots law is the practice of precognoscing a witness, that is the taking of a factual statement from witnesses by both prosecution and defence after indictment or claim but before trial. This is often undertaken by trainee lawyers or precognition officers employed by firms; anecdotal evidence suggests many of these are former police officers.

George Alexander Way of Plean CStJ is a Scottish Sheriff and former Procurator Fiscal of the Court of the Lord Lyon in Scotland. In November 2015, it was announced that he was to be the first Scottish Sheriff to be appointed a member of the Royal Household in Scotland as Falkland Pursuivant Extraordinary at the Court of the Lord Lyon. In December 2017, he was promoted to Carrick Pursuivant in Ordinary and then to Rothesay Herald in 2024. In 2020, he was appointed Chancellor of the Diocese of Brechin. In June 2021, he was appointed as Genealogist of the Priory of Scotland in the Most Venerable Order of St.John.

Scots criminal law relies far more heavily on common law than in England and Wales. Scottish criminal law includes offences against the person of murder, culpable homicide, rape and assault, offences against property such as theft and malicious mischief, and public order offences including mobbing and breach of the peace. Scottish criminal law can also be found in the statutes of the UK Parliament with some areas of criminal law, such as misuse of drugs and traffic offences appearing identical on both sides of the Border. Scottish criminal law can also be found in the statute books of the Scottish Parliament such as the Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2009 and Prostitution (Scotland) Act 2007 which only apply to Scotland. In fact, the Scots requirement of corroboration in criminal matters changes the practical prosecution of crimes derived from the same enactment. Corroboration is not required in England or in civil cases in Scotland. Scots law is one of the few legal systems that require corroboration.

A fiscal fine is a form of deferred prosecution agreement in Scotland issued by a procurator fiscal for certain summary offences as an alternative to prosecution. Alternatives to prosecution are called direct measures in Scotland.

The Court of the Lord Lyon, or Lyon Court, is a standing court of law, based in New Register House in Edinburgh, which regulates heraldry in Scotland. The Lyon Court maintains the register of grants of arms, known as the Public Register of All Arms and Bearings in Scotland, as well as records of genealogies.

Scots law is the legal system of Scotland. It is a hybrid or mixed legal system containing civil law and common law elements, that traces its roots to a number of different historical sources. Together with English law and Northern Irish law, it is one of the three legal systems of the United Kingdom. Scots law recognises four sources of law: legislation, legal precedent, specific academic writings, and custom. Legislation affecting Scotland and Scots law is passed by the Scottish Parliament on all areas of devolved responsibility, and the United Kingdom Parliament on reserved matters. Some legislation passed by the pre-1707 Parliament of Scotland is still also valid.

In Scots law, an interdict is a court order to stop someone from breaching someone else's rights. They can be issued by the Court of Session or a Sheriff Court. The equivalent term in England is an injunction. A temporary interdict is called an interim interdict. A court will grant an interim interdict if there is a prima facie case and on the balance of convenience the remedy should be granted. Breaching an interdict can result in a fine or imprisonment.

The Sheriff Personal Injury Court is a Scottish court with exclusive competence over claims relating to personal injury where the case is for a work-related accident claim in excess of £1,000, where the total amount claimed is in excess of £5,000, or where a sheriff in a local sheriff court remits proceedings to the Personal Injury Court. It has concurrent jurisdiction with the Court of Session for all claims in excess of £100,000, and concurrent jurisdiction with the local sheriff courts for personal injury claims within its competence.