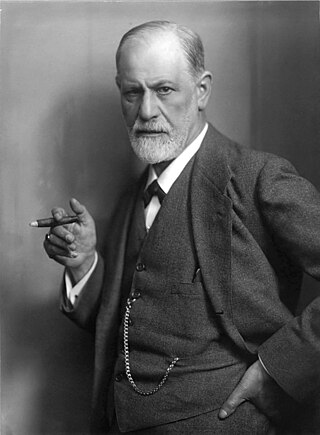

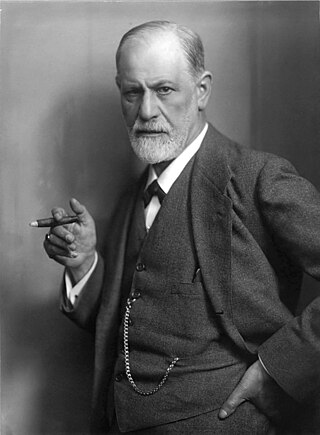

Psychoanalysis is a set of theories and therapeutic techniques that deal in part with the unconscious mind, and which together form a method of treatment for mental disorders. The discipline was established in the early 1890s by Sigmund Freud, whose work stemmed partly from the clinical work of Josef Breuer and others. Freud developed and refined the theory and practice of psychoanalysis until his death in 1939. In an encyclopedic article, he identified the cornerstones of psychoanalysis as "the assumption that there are unconscious mental processes, the recognition of the theory of repression and resistance, the appreciation of the importance of sexuality and of the Oedipus complex." Freud's colleagues Alfred Adler and Carl Gustav Jung developed offshoots of psychoanalysis which they called individual psychology (Adler) and analytical psychology (Jung), although Freud himself wrote a number of criticisms of them and emphatically denied that they were forms of psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysis was later developed in different directions by neo-Freudian thinkers, such as Erich Fromm, Karen Horney, and Harry Stack Sullivan.

Sigmund Freud was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies seen as originating from conflicts in the psyche, through dialogue between patient and psychoanalyst, and the distinctive theory of mind and human agency derived from it.

Alfred Ernest Jones was a Welsh neurologist and psychoanalyst. A lifelong friend and colleague of Sigmund Freud from their first meeting in 1908, he became his official biographer. Jones was the first English-speaking practitioner of psychoanalysis and became its leading exponent in the English-speaking world. As President of both the International Psychoanalytical Association and the British Psycho-Analytical Society in the 1920s and 1930s, Jones exercised a formative influence in the establishment of their organisations, institutions and publications.

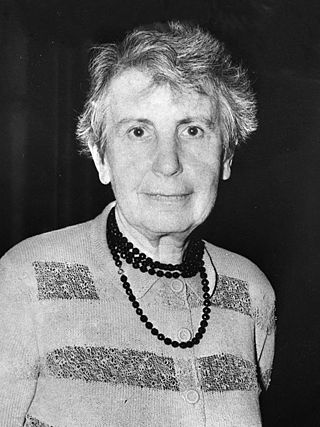

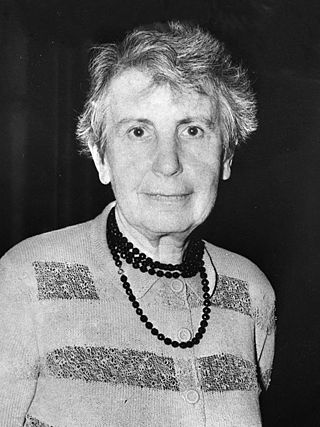

Anna Freud CBE was a British psychoanalyst of Austrian–Jewish descent. She was born in Vienna, the sixth and youngest child of Sigmund Freud and Martha Bernays. She followed the path of her father and contributed to the field of psychoanalysis. Alongside Hermine Hug-Hellmuth and Melanie Klein, she may be considered the founder of psychoanalytic child psychology.

Neo-Freudianism is a psychoanalytic approach derived from the influence of Sigmund Freud but extending his theories towards typically social or cultural aspects of psychoanalysis over the biological.

Theodor Reik was a psychoanalyst who trained as one of Freud's first students in Vienna, Austria, and was a pioneer of lay analysis in the United States.

Abraham Arden Brill was an Austrian-born psychiatrist who spent almost his entire adult life in the United States. He was the first psychoanalyst to practice in the United States and the first translator of Sigmund Freud into English.

Dora is the pseudonym given by Sigmund Freud to a patient whom he diagnosed with hysteria, and treated for about eleven weeks in 1900. Her most manifest hysterical symptom was aphonia, or loss of voice. The patient's real name was Ida Bauer (1882–1945); her brother Otto Bauer was a leading member of the Austro-Marxist movement.

Franz Gabriel Alexander was a Hungarian-American psychoanalyst and physician, who is considered one of the founders of psychosomatic medicine and psychoanalytic criminology.

The American Psychoanalytic Association (APsA) is an association of psychoanalysts in the United States. APsaA serves as a scientific and professional organization with a focus on education, research, and membership development.

Hermann/Herman Nunberg was a psychoanalyst and neurologist.

Fixation is a concept that was originated by Sigmund Freud (1905) to denote the persistence of anachronistic sexual traits. The term subsequently came to denote object relationships with attachments to people or things in general persisting from childhood into adult life.

The National Psychological Association for Psychoanalysis (NPAP) is an institution in New York City by Theodore Reik in 1948, established in response to the controversy over lay analysis and the question of the training of psychoanalysts in the United States.

Edward George Glover was a British psychoanalyst. He first studied medicine and surgery, and it was his elder brother, James Glover (1882–1926) who attracted him towards psychoanalysis. Both brothers were analysed in Berlin by Karl Abraham; indeed, the "list of Karl Abraham's analysands reads like a roster of psychoanalytic eminence: the leading English analysts Edward and James Glover" at the top. He then settled down in London where he became an influential member of the British Psycho-Analytical Society in 1921. He was also close to Ernest Jones.

A training analysis is a psychoanalysis undergone by a candidate as a part of her/his training to be a psychoanalyst; the (senior) psychoanalyst who performs such an analysis is called a training analyst.

In psychoanalysis, evenly suspended attention is a form of analytical attention that is removed from both theoretical presuppositions and therapeutic goals. By not fixating on any particular part of the analysand's communication and allowing freedom of the unconscious, the analyst can mindfully benefit from the counterpart rule of free association, on the part of the analysand, to analyze their symptomatic patterns and behaviors.

Hanns Sachs was one of the earliest psychoanalysts, and a close personal friend of Sigmund Freud. He became a member of Freud's Secret Committee of six in 1912, Freud describing him as one "in whom my confidence is unlimited in spite of the shortness of our acquaintance".

Ernst Simmel was a German-American neurologist and psychoanalyst.

The Question of Lay Analysis is a 1926 book by Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, advocating the right of non-doctors, or 'lay' people, to be psychoanalysts. It was written in response to Theodore Reik's being prosecuted for being a non-medical, or lay, analyst in Austria.

Kurt Robert Eissler was an Austrian psychoanalyst and a close associate and follower of Sigmund Freud.