In psychology, fantasy is a broad range of mental experiences, mediated by the faculty of imagination in the human brain, and marked by an expression of certain desires through vivid mental imagery. Fantasies are generally associated with scenarios that are impossible or unlikely to happen.

Jean William Fritz Piaget was a Swiss psychologist known for his work on child development. Piaget's theory of cognitive development and epistemological view are together called genetic epistemology.

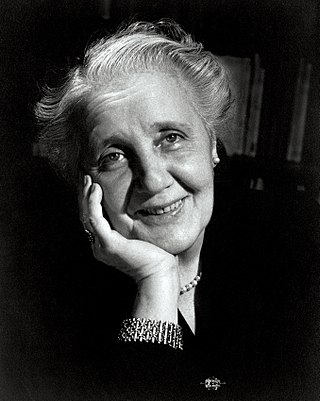

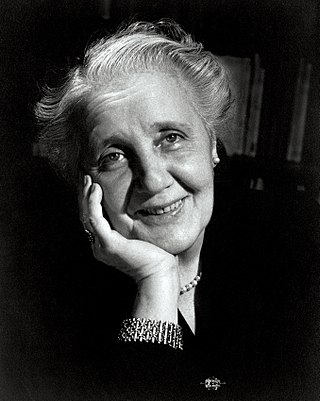

Melanie Klein was an Austrian-British author and psychoanalyst known for her work in child analysis. She was the primary figure in the development of object relations theory. Klein suggested that pre-verbal existential anxiety in infancy catalyzed the formation of the unconscious, which resulted in the unconscious splitting of the world into good and bad idealizations. In her theory, how the child resolves that split depends on the constitution of the child and the character of nurturing the child experiences. The quality of resolution can inform the presence, absence, and/or type of distresses a person experiences later in life.

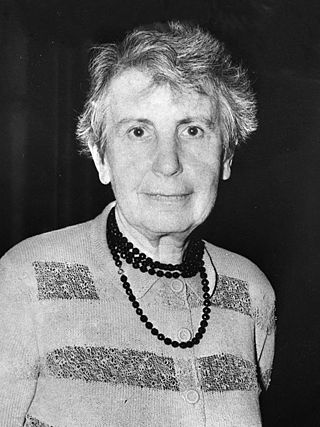

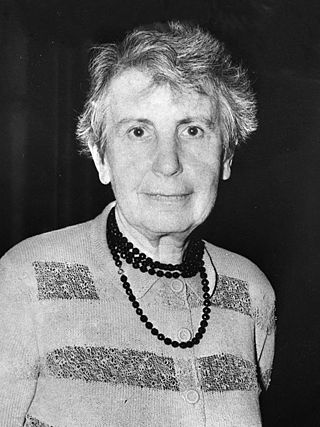

Anna Freud CBE was a British psychoanalyst of Austrian–Jewish descent. She was born in Vienna, the sixth and youngest child of Sigmund Freud and Martha Bernays. She followed the path of her father and contributed to the field of psychoanalysis. Alongside Hermine Hug-Hellmuth and Melanie Klein, she may be considered the founder of psychoanalytic child psychology.

Object relations theory is a school of thought in psychoanalytic theory and psychoanalysis centered around theories of stages of ego development. Its concerns include the relation of the psyche to others in childhood and the exploration of relationships between external people, as well as internal images and the relations found in them. Adherents to this school of thought maintain that the infant's relationship with the mother primarily determines the formation of their personality in adult life. Attachment is the bedrock of the development of the self, i.e. the psychic organization that creates one's sense of identity.

The Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust is a specialist mental health trust based in north London. The Trust specialises in talking therapies. The education and training department caters for 2,000 students a year from the United Kingdom and abroad. The Trust is based at the Tavistock Centre in Swiss Cottage. The founding organisation was the Tavistock Institute of Medical Psychology founded in 1920 by Hugh Crichton-Miller.

Nancy Julia Chodorow is an American sociologist and professor. She began teaching at Wellesley College in 1973 and at the University of California, Santa Cruz, from 1974 until 1986. She was a Sociology and Clinical Psychology professor at the University of California, Berkeley until 1986. Subsequently, she taught psychiatry at Harvard Medical School/Cambridge Health Alliance.

Sabina Nikolayevna Spielrein was a Russian physician and one of the first female psychoanalysts. She was in succession the patient, then student, then colleague of Carl Gustav Jung, with whom she had an intimate relationship during 1908–1910, as is documented in their correspondence from the time and her diaries. She also met, corresponded, and had a collegial relationship with Sigmund Freud. She worked with and psychoanalysed Swiss developmental psychologist Jean Piaget. She worked as a psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, teacher and paediatrician in Switzerland and Russia. In a thirty-year professional career, she published over 35 papers in three languages, covering psychoanalysis, developmental psychology, psycholinguistics and educational psychology. Among her works in the field of psychoanalysis is the essay titled "Destruction as the Cause of Coming Into Being", written in German in 1912.

The Malting House School was an experimental educational institution that operated from 1924 to 1929. It was set up by the eccentric and, at the time, wealthy Geoffrey Pyke in his family home in Cambridge and it was run by Susan Sutherland Isaacs. Although it was open for only a few years, the radical ideas explored in this institution have remained influential up until the present day. Since 2004 it has been owned by Darwin College, Cambridge and used as accommodation.

Hermine Hug-Hellmuth was an Austrian psychoanalyst. She is regarded as the first psychoanalyst practicing with children and the first to conceptualize the technique of psychoanalysing children.

Mary Nina Searl was an English psychologist and one of the earliest British child psychoanalysts, who came by way of the Brunswick Square Clinic to become a member of the British Psychoanalytical Society. She was analysed by Hanns Sachs.

Grete Bibring was an Austrian-American psychoanalyst who became the first female full professor at Harvard Medical School in 1961.

Maria Weigl Piers was an Austrian-born American psychologist, social worker, educator and prolific author, whose career was especially devoted to the psycho-social development of children. With Barbara T. Bowman and Lorraine Wallach, Piers founded the Chicago School for Early Childhood Education, later renamed the Erikson Institute for Early Childhood Education in recognition of the work of Erik Erikson, a close friend and colleague of Piers. Piers served as professor and dean at Erikson Institute, and brought her particular interest and expertise in psychoanalytic theory and practice to the Erikson curriculum. The Erikson Institute is widely recognized as one of the world's leading academic institutions in the field of early childhood development.

Clare Winnicott, OBE was an English social worker, civil servant, psychoanalyst and teacher. She played a pivotal role in the passing of the Children Act 1948. Alongside her husband, D. W. Winnicott, Clare would go on to become a prolific writer and prominent social worker and children's advocate in 20th century England.

Therese Benedek was a Hungarian-American psychoanalyst, researcher, and educator. Active in Germany and the United States between the years 1921 and 1977, she was regarded for her work on psychosomatic medicine, women's psychosexual development, sexual dysfunction, and family relationships. She was a faculty and staff member of the Chicago Institute for Psychoanalysis from 1936 to 1969.

Rose Edgcumbe, sometimes known as Rose Edgcumbe Theobald, was a British psychoanalyst, psychologist and child development researcher.

Nathan Isaacs (1895–1966) was a British educational psychologist. He worked in the metals trade, but after his marriage to Susan Sutherland Fairhurst, they were partners in her work on early education.

William Broadhurst Brierley (1889–1963) was an English mycologist. He is known particularly for his work on "grey mould".

Anne-Marie Sandler was a Swiss-born British psychologist and psychoanalyst noted for her clinical observation of the relationship dynamic between blind infants and their mothers in a project spearheaded by Anna Freud.

Elisabeth Rozetta Geleerd Loewenstein was a Dutch-American psychoanalyst. Born to an upper-middle-class family in Rotterdam, Geleerd studied psychoanalysis in Vienna, then London, under Anna Freud. Building a career in the United States, she became one of the nation's major practitioners in child and adolescent psychoanalysis throughout the mid-20th century. Geleerd specialized in the psychoanalysis of psychosis, including schizophrenia, and was an influential writer on psychoanalysis in childhood schizophrenia. She was one of the first writers to consider the concept of borderline personality disorder in childhood.