Geodesy or geodetics is the science of measuring and representing the geometry, gravity, and spatial orientation of the Earth in temporally varying 3D. It is called planetary geodesy when studying other astronomical bodies, such as planets or circumplanetary systems. Geodesy is an earth science and many consider the study of Earth's shape and gravity to be central to that science. It is also a discipline of applied mathematics.

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. These points are usually on the surface of the Earth, and they are often used to establish maps and boundaries for ownership, locations, such as the designated positions of structural components for construction or the surface location of subsurface features, or other purposes required by government or civil law, such as property sales.

Physical geodesy is the study of the physical properties of Earth's gravity and its potential field, with a view to their application in geodesy.

A theodolite is a precision optical instrument for measuring angles between designated visible points in the horizontal and vertical planes. The traditional use has been for land surveying, but it is also used extensively for building and infrastructure construction, and some specialized applications such as meteorology and rocket launching.

A spirit level, bubble level, or simply a level, is an instrument designed to indicate whether a surface is horizontal (level) or vertical (plumb). Two basic designs exist: tubular and bull's eye . Different types of spirit levels may be used by carpenters, stonemasons, bricklayers, other building trades workers, surveyors, millwrights and other metalworkers, and in some photographic or videographic work.

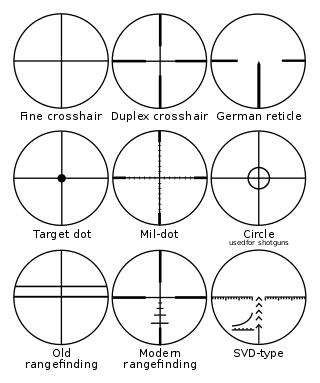

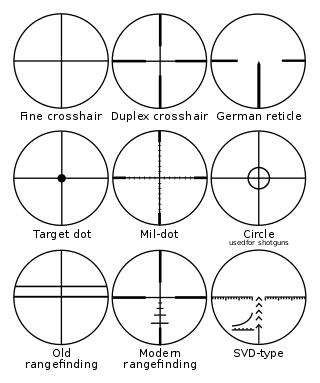

A reticle, or reticule also known as a graticule, is a pattern of fine lines or markings built into the eyepiece of an optical device such as a telescopic sight, spotting scope, theodolite, optical microscope or the screen of an oscilloscope, to provide measurement references during visual inspections. Today, engraved lines or embedded fibers may be replaced by a digital image superimposed on a screen or eyepiece. Both terms may be used to describe any set of patterns used for aiding visual measurements and calibrations, but in modern use reticle is most commonly used for weapon sights, while graticule is more widely used for non-weapon measuring instruments such as oscilloscope display, astronomic telescopes, microscopes and slides, surveying instruments and other similar devices.

A total station or total station theodolite is an electronic/optical instrument used for surveying and building construction. It is an electronic transit theodolite integrated with electronic distance measurement (EDM) to measure both vertical and horizontal angles and the slope distance from the instrument to a particular point, and an on-board computer to collect data and perform triangulation calculations.

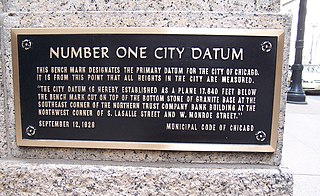

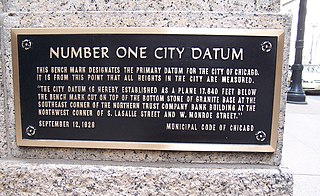

A geodetic datum or geodetic system is a global datum reference or reference frame for unambiguously representing the position of locations on Earth by means of either geodetic coordinates or geocentric coordinates. Datums are crucial to any technology or technique based on spatial location, including geodesy, navigation, surveying, geographic information systems, remote sensing, and cartography. A horizontal datum is used to measure a horizontal position, across the Earth's surface, in latitude and longitude or another related coordinate system. A vertical datum is used to measure the elevation or depth relative to a standard origin, such as mean sea level (MSL). A three-dimensional datum enables the expression of both horizontal and vertical position components in a unified form. The concept can be generalized for other celestial bodies as in planetary datums.

A level is an optical instrument used to establish or verify points in the same horizontal plane in a process known as levelling. It is used in conjunction with a levelling staff to establish the relative height or levels of objects or marks. It is widely used in surveying and construction to measure height differences and to transfer, measure, and set heights of known objects or marks.

Stadiametric rangefinding, or the stadia method, is a technique of measuring distances with a telescopic instrument. The term stadia comes from a Greek unit of length Stadion which was the typical length of a sports stadium of the time. Stadiametric rangefinding is used for surveying and in the telescopic sights of firearms, artillery pieces, or tank guns, as well as some binoculars and other optics. It is still widely used in long-range military sniping, but in many professional applications it is being replaced with microwave, infrared, or laser rangefinding methods. Although much easier to use, electronic rangefinders can give away the shooter's position to a well-equipped adversary, and the need for accurate range estimation has existed for much longer than electronic rangefinders small and rugged enough to be suitable for military use.

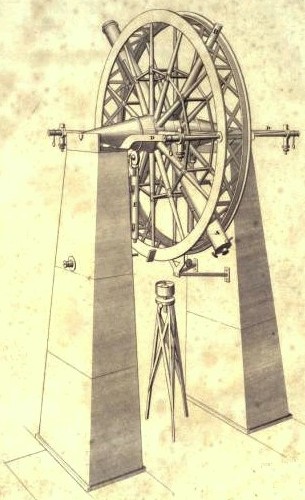

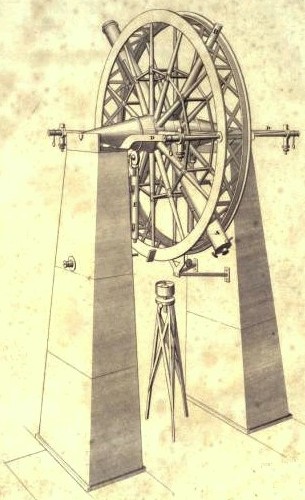

The meridian circle is an instrument for timing of the passage of stars across the local meridian, an event known as a culmination, while at the same time measuring their angular distance from the nadir. These are special purpose telescopes mounted so as to allow pointing only in the meridian, the great circle through the north point of the horizon, the north celestial pole, the zenith, the south point of the horizon, the south celestial pole, and the nadir. Meridian telescopes rely on the rotation of the sky to bring objects into their field of view and are mounted on a fixed, horizontal, east–west axis.

Tacheometry is a system of rapid surveying, by which the horizontal and vertical positions of points on the Earth's surface relative to one another are determined using a tacheometer. It is used without a chain or tape for distance measurement and without a separate levelling instrument for relative height measurements.

The Australian Height Datum was introduced in 1971 as the official vertical datum for Australia, and thereby serves as the benchmark to which all height measurements are referred. The Australian Height Datum is an amalgamation of decades of spirit levelling work conducted by numerous state and territory authorities across the country, and was corrected to align with the mean sea level observations of thirty tide gauges positioned around the entire coastline. While it remains the published vertical datum for all surveying and engineering operations performed throughout Australia, newer technologies have uncovered numerous deficiencies, offsets and distortions within the Australian Height Datum, leading to discussions about defining a new Australian vertical datum.

Polar alignment is the act of aligning the rotational axis of a telescope's equatorial mount or a sundial's gnomon with a celestial pole to parallel Earth's axis.

Stadia marks, also called stadia lines or stadia hairs, are crosshairs on the reticle of a theodolite or other surveying instrument that allow stadiametric rangefinding.

A level staff, also called levelling rod, is a graduated wooden or aluminium rod, used with a levelling instrument to determine the difference in height between points or heights of points above a vertical datum. When used for stadiametric rangefinding, the level staff is called a stadia rod.

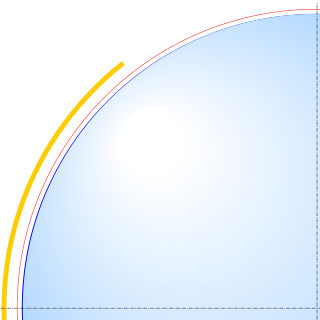

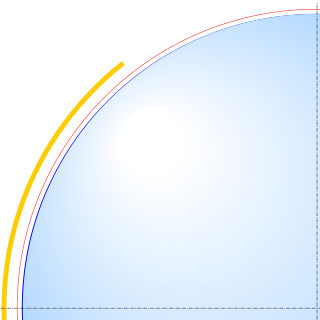

An Earth ellipsoid or Earth spheroid is a mathematical figure approximating the Earth's form, used as a reference frame for computations in geodesy, astronomy, and the geosciences. Various different ellipsoids have been used as approximations.

The Drift Sight was a bombsight developed by Harry Wimperis in 1916 for the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS). It used a simple mechanical device to measure the wind speed from the air, and used that measurement to calculate the wind's effects on the trajectory of the bombs. The Drift Sight eliminated the need for a stopwatch to perform this calculation, as on earlier devices, and greatly eased the bomb aimer's workload.

This is a glossary of levelling terms. Levelling is a surveying method used to find relative height, one use of which is to ensure ground is level during construction, for example, when excavating to prepare for laying a foundation for a house.

Vertical position or vertical location is a position along a vertical direction above or below a given vertical datum . Vertical distance or vertical separation is the distance between two vertical positions. Many vertical coordinates exist for expressing vertical position: depth, height, altitude, elevation, etc. Points lying on an equigeopotential surface are said to be on the same vertical level, as in a water level.