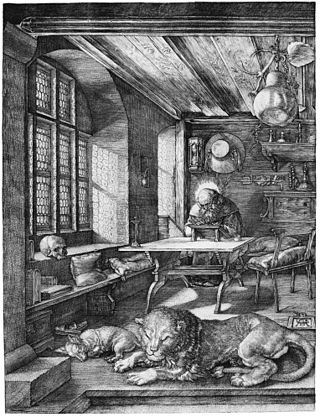

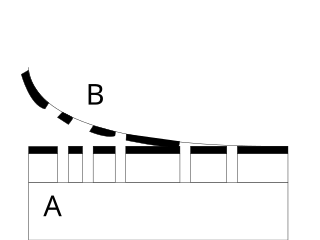

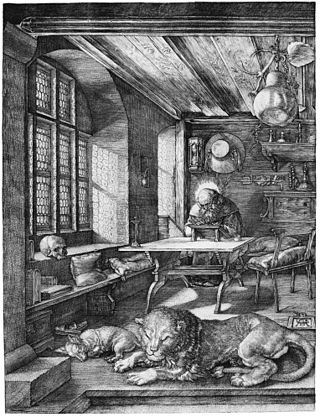

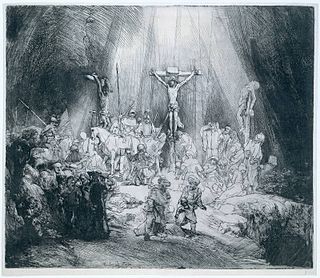

Etching is traditionally the process of using strong acid or mordant to cut into the unprotected parts of a metal surface to create a design in intaglio (incised) in the metal. In modern manufacturing, other chemicals may be used on other types of material. As a method of printmaking, it is, along with engraving, the most important technique for old master prints, and remains in wide use today. In a number of modern variants such as microfabrication etching and photochemical milling, it is a crucial technique in modern technology, including circuit boards.

Printmaking is the process of creating artworks by printing, normally on paper, but also on fabric, wood, metal, and other surfaces. "Traditional printmaking" normally covers only the process of creating prints using a hand processed technique, rather than a photographic reproduction of a visual artwork which would be printed using an electronic machine ; however, there is some cross-over between traditional and digital printmaking, including risograph.

Engraving is the practice of incising a design on a hard, usually flat surface by cutting grooves into it with a burin. The result may be a decorated object in itself, as when silver, gold, steel, or glass are engraved, or may provide an intaglio printing plate, of copper or another metal, for printing images on paper as prints or illustrations; these images are also called "engravings". Engraving is one of the oldest and most important techniques in printmaking. Wood engravings, a form of relief printing and stone engravings, such as petroglyphs, are not covered in this article.

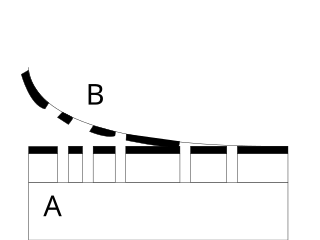

Mezzotint is a monochrome printmaking process of the intaglio family. It was the first printing process that yielded half-tones without using line- or dot-based techniques like hatching, cross-hatching or stipple. Mezzotint achieves tonality by roughening a metal plate with thousands of little dots made by a metal tool with small teeth, called a "rocker". In printing, the tiny pits in the plate retain the ink when the face of the plate is wiped clean. This technique can achieve a high level of quality and richness in the print, and produce a furniture print which is large and bold enough to be framed and hung effectively in a room.

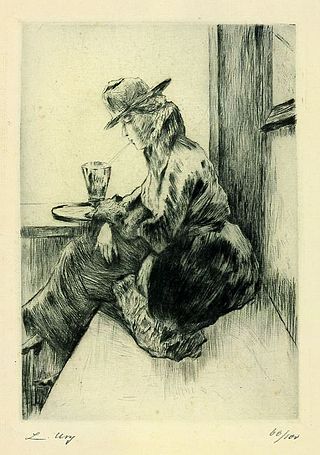

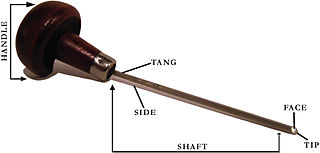

Drypoint is a printmaking technique of the intaglio family, in which an image is incised into a plate with a hard-pointed "needle" of sharp metal or diamond point. In principle, the method is practically identical to engraving. The difference is in the use of tools, and that the raised ridge along the furrow is not scraped or filed away as in engraving. Traditionally the plate was copper, but now acetate, zinc, or plexiglas are also commonly used. Like etching, drypoint is easier to master than engraving for an artist trained in drawing because the technique of using the needle is closer to using a pencil than the engraver's burin.

Aquatint is an intaglio printmaking technique, a variant of etching that produces areas of tone rather than lines. For this reason it has mostly been used in conjunction with etching, to give both lines and shaded tone. It has also been used historically to print in colour, both by printing with multiple plates in different colours, and by making monochrome prints that were then hand-coloured with watercolour.

Collagraphy is a printmaking process in which materials are glued or sealed to a rigid substrate to create a plate. Once inked, the plate becomes a tool for imprinting the design onto paper or another medium. The resulting print is termed a collagraph. The term "collagraph" was coined by Glen Alps in the 1950s, and is derived from the Greek word koll or kolla, meaning glue, and graph, meaning the activity of drawing.

Relief printing is a family of printing methods where a printing block, plate or matrix, which has had ink applied to its non-recessed surface, is brought into contact with paper. The non-recessed surface will leave ink on the paper, whereas the recessed areas will not. A printing press may not be needed, as the back of the paper can be rubbed or pressed by hand with a simple tool such as a brayer or roller. In contrast, in intaglio printing, the recessed areas are printed.

Rotogravure is a type of intaglio printing process, which involves engraving the image onto an image carrier. In gravure printing, the image is engraved onto a cylinder because, like offset printing and flexography, it uses a rotary printing press.

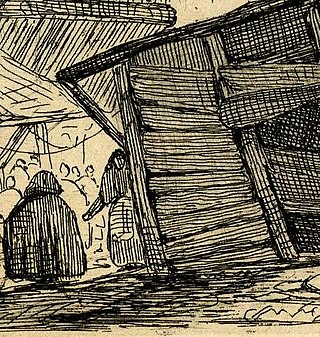

Wood engraving is a printmaking technique, in which an artist works an image into a block of wood. Functionally a variety of woodcut, it uses relief printing, where the artist applies ink to the face of the block and prints using relatively low pressure. By contrast, ordinary engraving, like etching, uses a metal plate for the matrix, and is printed by the intaglio method, where the ink fills the valleys, the removed areas. As a result, the blocks for wood engravings deteriorate less quickly than the copper plates of engravings, and have a distinctive white-on-black character.

Hatching is an artistic technique used to create tonal or shading effects by drawing closely spaced parallel lines. When lines are placed at an angle to one another, it is called cross-hatching. Hatching is also sometimes used to encode colours in monochromatic representations of colour images, particularly in heraldry.

Intaglio is the family of printing and printmaking techniques in which the image is incised into a surface and the incised line or sunken area holds the ink. It is the direct opposite of a relief print where the parts of the matrix that make the image stand above the main surface.

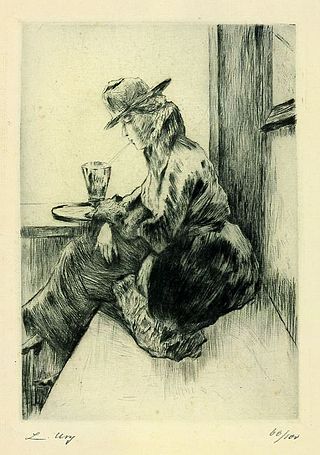

The etching revival was the re-emergence and invigoration of etching as an original form of printmaking during the period approximately from 1850 to 1930. The main centres were France, Britain and the United States, but other countries, such as the Netherlands, also participated. A strong collector's market developed, with the most sought-after artists achieving very high prices. This came to an abrupt end after the 1929 Wall Street crash wrecked what had become a very strong market among collectors, at a time when the typical style of the movement, still based on 19th-century developments, was becoming outdated.

Viscosity printing is a multi-color printmaking technique that incorporates principles of relief printing and intaglio printing. It was pioneered by Stanley William Hayter.

Steel engraving is a technique for printing illustrations based on steel instead of copper. It has been rarely used in artistic printmaking, although it was much used for reproductions in the 19th century. Steel engraving was introduced in 1792 by Jacob Perkins (1766–1849), an American inventor, for banknote printing. When Perkins moved to London in 1818, the technique was adapted in 1820 by Charles Warren and especially by Charles Heath (1785–1848) for Thomas Campbell's Pleasures of Hope, which contained the first published plates engraved on steel. The new technique only partially replaced the other commercial techniques of that time such as wood engraving, copper engraving and later lithography.

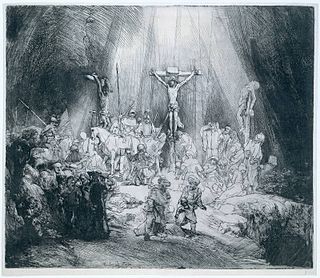

An old master print is a work of art produced by a printing process within the Western tradition. The term remains current in the art trade, and there is no easy alternative in English to distinguish the works of "fine art" produced in printmaking from the vast range of decorative, utilitarian and popular prints that grew rapidly alongside the artistic print from the 15th century onwards. Fifteenth-century prints are sufficiently rare that they are classed as old master prints even if they are of crude or merely workmanlike artistic quality. A date of about 1830 is usually taken as marking the end of the period whose prints are covered by this term.

Stipple engraving is a technique used to create tone in an intaglio print by distributing a pattern of dots of various sizes and densities across the image. The pattern is created on the printing plate either in engraving by gouging out the dots with a burin, or through an etching process. Stippling was used as an adjunct to conventional line engraving and etching for over two centuries, before being developed as a distinct technique in the mid-18th century.

À la poupée is a largely historic intaglio printmaking technique for making colour prints by applying different ink colours to a single printing plate using ball-shaped wads of cloth, one for each colour. The paper has just one run through the press, but the inking needs to be carefully re-done after each impression is printed. Each impression usually varies at least slightly, sometimes very significantly.

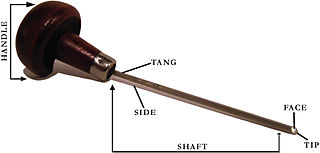

A burin is a steel cutting tool used in engraving, from the French burin. Its older English name and synonym is graver.

In printmaking, surface tone, or surface-tone, is produced by deliberately or accidentally not wiping all the ink off the surface of the printing plate, so that parts of the image have a light tone from the film of ink left. Tone in printmaking meaning areas of continuous colour, as opposed to the linear marks made by an engraved or drawn line. The technique can be used with all the intaglio printmaking techniques, of which the most important are engraving, etching, drypoint, mezzotint and aquatint. It requires individual attention on the press before each impression is printed, and is mostly used by artists who print their own plates, such as Rembrandt, "the first master of this art", who made great use of it.