Related Research Articles

Eastern Christianity comprises Christian traditions and church families that originally developed during classical and late antiquity in Western Asia, Asia Minor, Eastern Europe, Southeastern Europe, the Caucasus, Northeast Africa, the Fertile Crescent and the Malabar coast of South Asia, and ephemerally parts of Persia, Central Asia and the Far East. The term does not describe a single communion or religious denomination.

The House of Wisdom, also known as the Grand Library of Baghdad, was a major Abbasid public academy and intellectual center in Baghdad and one of the world's largest public libraries during the Islamic Golden Age. The House of Wisdom was founded either as a library for the collections of the Caliph Harun al-Rashid in the late 8th century or was a private collection created by al-Mansur to house rare books and collections of poetry in Arabic. During the reign of the Caliph al-Ma'mun, it was turned into a public academy and a library.

Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-Ibadi (Arabic: أبو زيد حنين بن إسحاق العبادي; ʾAbū Zayd Ḥunayn ibn ʾIsḥāq al-ʿIbādī was an influential Arab Nestorian Christian translator, scholar, physician, and scientist. During the apex of the Islamic Abbasid era, he worked with a group of translators, among whom were Abū 'Uthmān al-Dimashqi, Ibn Mūsā al-Nawbakhti, and Thābit ibn Qurra, to translate books of philosophy and classical Greek and Persian texts into Arabic and Syriac.

The Bukhtīshūʿ were a family of either Persian or Syrian Eastern Christian physicians from the seventh, eighth, and ninth centuries, spanning six generations and 250 years. The Middle Persian-Syriac name which can be found as early as at the beginning of the 5th century refers to the eponymous ancestor of this "Syro-Persian Nestorian family". Some members of the family served as the personal physicians of Caliphs. Jurjis son of Bukht-Yishu was awarded 10,000 dinars by al-Mansur after attending to his malady in 765AD. It is even said that one of the members of this family was received as physician to Ali ibn Husayn Zayn al-Abidin, the Shia Imam, during his illness in the events of Karbala.

Jabril ibn Bukhtishu, also written as Bakhtyshu, was an 8th-9th century physician from the Bukhtishu family of Assyrian Nestorian physicians from the Persian Academy of Gundishapur. He was a Nestorian and spoke the Syriac language.

Yuhanna ibn Bukhtishu was a 9th-century Persian or Syriac physician from Khuzestan, Persia.

Abu al-Faraj is a title or given name, derived from the name Faraj, of Arabic origins. During the Middle Ages, the name Abu al-Faraj was a title for many Arab and Jewish poets and scholars.

Qusta ibn Luqa, also known as Costa ben Luca or Constabulus (820–912) was a Syrian Melkite Christian physician, philosopher, astronomer, mathematician and translator. He was born in Baalbek. Travelling to parts of the Byzantine Empire, he brought back Greek texts and translated them into Arabic.

Sergius of Reshaina was a physician and priest during the 6th century. He is best known for translating medical works from Greek to Syriac, which were eventually, during the Abbasid Caliphate of the late 8th- & 9th century, translated into Arabic. Reshaina, where he lived, is located about midway between the then intellectual centres of Edessa and Nisibis, in northern Mesopotamia.

The Graeco-Arabic translation movement was a large, well-funded, and sustained effort responsible for translating a significant volume of secular Greek texts into Arabic. The translation movement took place in Baghdad from the mid-eighth century to the late tenth century.

Christian influences in Islam can be traced back to Eastern Christianity, which surrounded the origins of Islam. Islam, emerging in the context of the Middle East that was largely Christian, was first seen as a Christological heresy known as the "heresy of the Ishmaelites", described as such in Concerning Heresy by Saint John of Damascus, a Syriac scholar.

Ishak, Ishaq or Eshaq is a surname and masculine given name, the Arabic form of Isaac. Ishak (Isaac) was the son of Ibrahim (Abraham) and Sarah, patriarchs in the Bible and the Quran. The name Ishak means ‘One who laughs’ because Sarah laughed when the angel told them that they would get a child.

Abū Zakarīyā’ Yaḥyá ibn ʿAdī known as Yahya ibn Adi (893–974) was a Syriac Jacobite Christian philosopher, theologian and translator working in Arabic.

Abū Bishr Mattā ibn Yūnus al-Qunnāʾī was an Arab Christian philosopher who played an important role in the transmission of the works of Aristotle to the Islamic world. He is famous for founding the Baghdad school of Aristotelian philosophers.

Yusuf al-Khuri, also known as Yusuf al-Khuri al-Qass, was a Christian priest, physician, mathematician, and translator of the Abbasid era.

Job of Edessa, called the Spotted, was a Christian natural philosopher and physician active in Baghdad and Khurāsān under the Abbasid Caliphate. He played an important role in transmitting Greek science to the Islamic world through his translations into Syriac.

Ḥabīb ibn Bahrīz, also called ʿAbdishoʿ bar Bahrīz, was a bishop and scholar of the Church of the East, famous for his translations from Syriac into Arabic. He also wrote original works on logic, canon law and apologetics.

References

- ↑ "Islamic Culture and the Medical Arts: Greek Influences". Nlm.nih.gov. 1998-04-15. Retrieved 2010-02-08.

- ↑ Barsoum (2003), pp. 331–333.

- ↑ Thomas 2003 , pp. 61

- ↑ Schadé, Johannes P. (2006). Encyclopedia of World Religions. Foreign Media Group. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-60136-000-7 . Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ↑ Lavenant, René (1919). Abdīšō Berika bar. Vol. 3.

- ↑ Bonner, Bonner; Ener, Mine; Singer, Amy (2003). Poverty and charity in Middle Eastern contexts. SUNY Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-7914-5737-5.

- ↑ Ruano, Eloy Benito; Burgos, Manuel Espadas (1992). 17e Congrès international des sciences historiques: Madrid, du 26 août au 2 septembre 1990. Comité international des sciences historiques. p. 527. ISBN 978-84-600-8154-8.

- ↑ Frye, R.N., ed. (1975). The Cambridge history of Iran (Repr. ed.). London: Cambridge U.P. p. 415. ISBN 978-0-521-20093-6.

Among the Christians also there were some of Persian origin or at least of immediate Persian background, among whom the most important are the Bukhtyishu' and Masuya (Masawaih) families. The members of the Bukhtyishu* family were directors of the Jundishapur hospital and produced many outstanding physicians. One of them, Jirjls, was called to Baghdad by the 'Abbasid caliph al-Mansur, to cure his dyspepsia.

- ↑ Philip Jenkins. The Lost History of Christianity. Harper One. 2008. ISBN 0061472808.

- ↑ Griffith, Sidney H. (15 December 1998). "Eutychius of Alexandria". Encyclopædia Iranica . Retrieved 2011-02-07.

- ↑ Loudon, Irvine (2002-03-07). Western Medicine: An Illustrated History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199248131 . Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ↑ Street, Tony (1 January 2015). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Arabic and Islamic Philosophy of Language and Logic: Farabian Aristotelianism . Retrieved 13 June 2016– via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ↑ Barsoum (2003)

- ↑ G., Strohmaier (24 April 2012). "Ḥunayn b. Isḥāḳ al-ʿIbādī". Encyclopaedia of Islam.

- ↑ "Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq | Arab scholar". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ Esposito, John L. (2000). The Oxford History of Islam. Oxford University Press. p. 160.:"The most famous of these translators was a Nestorian (Christian) Assyrian by the name of Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-Ibadi (808–73)."

- ↑ Guscin 2016 , p. 156.

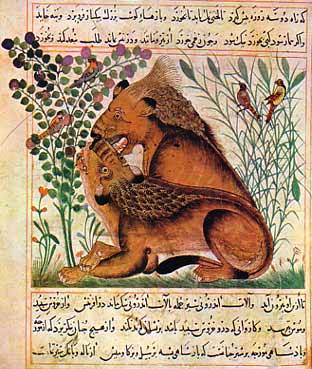

- ↑ Anna Contadini, 'A Bestiary Tale: Text and Image of the Unicorn in the Kitāb naʿt al-hayawān (British Library, or. 2784)', Muqarnas, 20 (2003), 17-33 (p. 17), https://www.jstor.org/stable/1523325.

- ↑ Chisholm 1911.

- ↑ "St. Jacob (James) of Edessa (+ June 5th, 708)".

- ↑ Mazzola (2018), p. 358.

- ↑ S. Brock, A brief outline of Syriac Literature, Moran Etho 9, Kottayam, Kerala: SEERI (1997), pp.56-57, 135

- ↑ Beeston, Alfred Felix Landon (1983). Arabic literature to the end of the Umayyad period. Cambridge University Press. p. 501. ISBN 978-0-521-24015-4 . Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ "Compendium of Medical Texts by Mesue, with Additional Writings by Various Authors". World Digital Library. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- ↑ Bosworth, C.E. (2000). History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume IV. Paris: UNESCO Publ. p. 306. ISBN 92-3-103654-8.

Comparable to al-Rāzi before him and to his own younger contemporary Ibn Sinā, al-Masihi represents the physician-philosopher of classical and Islamic tradition. From the point of view of religious history, it is also of interest that he was descended from Iranian Christians and held, albeit discreetly, to his faith.

- ↑ Sarton, George (1975). Introduction to the History of Science: From Homer to Omar Khayyam. Vol. 1. R. E. Krieger Pub. Co. p. 574. ISBN 978-0-88275-172-6.

- ↑ William Wright, A short history of Syriac literature, p.250, n.3.

- ↑ Rius 2007.

- ↑ Worrell, W. H. (1944). "Qusta Ibn Luqa on the Use of the Celestial Globe". Isis. 35 (4): 285–293. doi:10.1086/358720. JSTOR 330840. S2CID 143503145.

- ↑ Al-Ghazal, Sharif (2004). Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine. 3: 12–13.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link) - ↑ Thomas & Roggema 2009 , pp. 567

- ↑ Aʿlam, Hūšang. "EBN AL-BAYṬĀR, ŻĪĀʾ-AL-DĪN ABŪ MOḤA – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

the Christian Persian physician Sābūr (Šāpūr) b. Sahl from Gondēšāpūr (d. 255/869) ...

- ↑ De Lacy O'Leary How Greek science passed to the Arabs "How Greek Science Passed to the Arabs" online 2002- Page 166 "Hunayn had many other friends and clients, mostly physicians of Jundi-Shapur and those who had removed to Baghdad and used the Arabic language, like Salmawaih ibn Bunan an alumnus of Jundi-Shapur who became court physician to ..."

- ↑ Prioreschi, Plinio (2001-01-01). A History of Medicine: Byzantine and Islamic medicine. Horatius Press. p. 223. ISBN 9781888456042 . Retrieved 29 December 2014.

Ali ibn Sahl Rabban al-Tabari, the son of a Syriac Christian scholar living in Persia on the Caspian Sea...

- ↑ Meyerhof, M. (2012-04-24). "Ibn al-Tilmīd̲h̲". Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition.

- ↑ Alexander Treiger (2016). "New Works by Theodore Abū Qurra Preserved under the name of Thaddeus of Edessa". Journal of Eastern Christian Studies. 68 (1): 1–51. doi:10.2143/JECS.68.1.3164936.

- ↑ Shahid, Irfan (2010). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, Part 2. Harvard University Press. pp. 179–181. ISBN 978-0884023470.

- ↑ Bonner, Michael David; Ener, Mine; Singer, Amy (2003). Poverty and charity in Middle Eastern contexts. SUNY Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-7914-8676-4 . Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ↑ Hamid Naseem Rafiabad, ed. World Religions and Islam: A Critical Study, Part 1 :149.

- ↑ Ira M. Lapidus, Islamic Societies to the Nineteenth Century: A Global History, (Cambridge University Press, 2012), 200.

Works cited

- Barsoum, Ephrem (2003). The Scattered Pearls: A History of Syriac Literature and Sciences. Translated by Matti Moosa (2nd ed.). Gorgias Press. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Guscin, Mark (2016). The Tradition of the Image of Edessa. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Mazzola, Marianna, ed. (2018). Bar 'Ebroyo's Ecclesiastical History : writing Church History in the 13th century Middle East. PSL Research University. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Rius, Mònica (2007). "Nasṭūlus: Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh". In Thomas Hockey; et al. (eds.). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 822–3. ISBN 9780387310220. (PDF version)

- Thomas, David (2003). Christians at the heart of Islamic rule: church life and scholarship in ʻAbbasid Iraq. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-12938-2 . Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- Thomas, David; Roggema, Barbara (2009), Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History. Volume 1 (600-900), BRILL, ISBN 9789004169753