Life

Virtually nothing is known of Gerasimos' biography. His only surviving work provides no information beyond what is indicated by the long title: that he was the abbot of the Greek Orthodox monastery of the Blessed Saint Symeon the Wonderworker outside of Antioch. He may have been a native of Antioch. Even his dates are unknown. He cannot have been writing earlier than the 9th century, since he cites the work of Theodore Abū Qurra, who died around 820. Nor can he have been writing later than 1268, when the monastery of Saint Symeon was destroyed by Sultan Baybars during his campaign against Antioch. It was never restored. The earliest surviving manuscript of his work dates to the 13th century. Most authorities place his writing in the 12th or 13th century, not long before the desctruction of the monastery, as there are no earlier references to his work.

Since Gerasimos was a rare name in Syria between the 9th and 13th centuries, several identifications with other known figures have been suggested for the author and apologist. Samuel Noble and Alexander Treiger suggest that the author may be Gerasimos, the "spiritual son" to whom Nikon of the Black Mountain addressed a letter, which he includes in his Taktikon. The subject of the letter is the Christianization of Georgia and Nikon was a monk at Saint Symeon from about 1060 until 1084. Abgar Bahkou and John Lamoreaux suggest that the apologist may be the scribe Gerasimos who lived in the monastery in the 13th century and worked on a manuscript containing the biographies of Saint Symeon the Wonderworker and his mother, the Blessed Martha.

Although his work provides no biographical details, it does show that Gerasimos received a good and broad education. He was familiar with Aristotelian logic as well as with pagan and Muslim authors. He is included as a saint in the synaxarion of Patriarch Makarios III of Antioch (died 1672) and in the patriarch's Kitāb al-naḥla (Book of the Bee).

Works

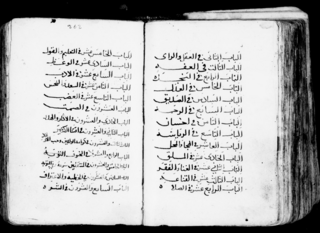

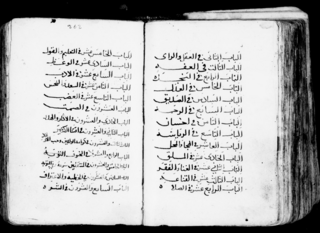

According to the synaxarion of Makarios III, Gerasimos wrote works called al-Mujādalāt (The Disputations), al-Mawaʿīẓ (The Sermons) and al-Shāfī (The Healer). Only the last work survives. Its full title is al-Kāfī fī l-maʿnā l-shāfī. [8] [9] [10] It is written in Arabic and divided into five parts, the last being far longer than the rest. [11] [12] It is detailed, learned, gracious and bereft of the rancor that came to characterize Christian apologia under Islam in the later Middle Ages.

In parts 1 and 2, Gerasimos discusses the nature of the true religion. Its purpose, he says, is to draw humans to God through commands and prohibitions and through the promise of reward or punishment in the afterlife. Further, it must be universal, not tribal, and communicable in language the people can understand. It must also be confirmed by miracles. He argues that all religions save Christianity draw humanity to earthly glory and serve its base desires. Of all the religions he knows, only Christianity is truly universal and accessible.

In parts 3 and 4, Gerasimos marshals "testimonies" in support of his views. He cites first Christian sources (Old and New Testament); then Jewish (such as Josephus); then contemporary pagan, that is, the writings of the Sabians of Ḥarrān; then ancient Greek philosophers (such as Socrates, Plato, Aristotle and Hermes Trismegistos); and finally a Muslim source, the Qurʾān.

In part 5, Gerasimos deals with six objections. The first objection states that Christianity cannot be the true religion because it is not the largest, has not always existed and is sometimes held in contempt. The next three objections are philosophical and allege the incompatibility of Christian doctrines (such as the Trinity and Incarnation) with reason, or the contradictoriness of others (such as divine foreknowledge and omnibenevolence). The final two objections target the Christian view of revelation and law.

Gerasimos has answers to all the objections. He argues that "the ascendancy of the umma of Muḥammad" and "the sword of Islam" are meant to discipline God's true children; that God's true nature demanded atonement rather than salvation by fiat; and that God reveals his law progressively as humanity passes through different stages of maturity. Thus the law of Christ supersedes the law of Moses, which supersedes the natural law.

Al-Kāfī fī l-maʿnā l-shāfī or portions of it are (or were) preserved in 23 manuscripts, not all of them traceable today. Only four of them are earlier than the 17th century:

- Sinai, Monastery of Saint Catherine, MS Ar. 448 (Kamil 495), folios 100v–127r, from the 13th century, contains only part 1 [14]

- Sinai, Monastery of Saint Catherine, MS Ar. 451 (Kamil 497), from 1323, contains only part 3 [15]

- Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Ar. 258, folios 73–78, from the 15th century, contains only the "testimonies" of the ancient Greeks [16]

- Beirut, Bibliothèque orientale [ fr ], MS 548, pages 243–271, from the 16th century, contains only the "testimonies" of the ancient Greeks and the Qurʾān

Saint Simeon, Saint Symeon or Saint-Siméon may refer to:

The Holy Lavra of Saint Sabbas, known in Arabic and Syriac as Mar Saba and historically as the Great Laura of Saint Sabas, is a Greek Orthodox monastery overlooking the Kidron Valley in the Bethlehem Governorate of Palestine, in the West Bank, at a point halfway between Bethlehem and the Dead Sea. The monks of Mar Saba and those of subsidiary houses are known as Sabaites.

Symeon or Simeon, distinguished as Symeon Metaphrastes (Latin) or Symeon the Metaphrast, was a Byzantine writer and official regarded as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church. His feast day is celebrated on 9 or 28 November. He is best known for his 10-volume Greek menologion, a collection of saints' lives.

Theodore Abū Qurrah was a 9th-century Melkite bishop and theologian who lived in the early Islamic period.

Bkerké is the episcopal see of the Maronite Catholic Patriarchate of Antioch of the Maronite Church in Lebanon, located 650 m above the bay of Jounieh, northeast of Beirut, in Lebanon.

Gerasimus of the Jordan was a Christian saint, monk and abbot of the 5th century AD.

Patriarch MacariusIII Ibn al-Za'im was Patriarch of Antioch from 1647 to 1672. He led a period of blossoming of his Church and is also remembered for his travels in Russia and for his involvement in the reforms of Russian Patriarch Nikon.

Abdallah ibn al-Fadl al-Antaki was an Arab Orthodox translator and theologian active in Antioch during the middle of the eleventh century, during a period of renewed Byzantine rule over the city. He was responsible for a large number of patristic translations, as well as original theological and philosophical works.

The Monastery of Saint Simeon Stylites the Younger is a former Christian monastery that lies on a hill roughly 29 kilometres southwest of Antakya and six kilometres to the east of Samandağ, in the southernmost Turkish province of Hatay. The site is extensive but the monastery buildings are in ruins.

Gerasimos is a Greek given name derived from Greek "γέρας". The suffix -ιμος gives the meaning "the one who deserves honour". It can also be anglicized as "Gerassimos" or "Gerasimus". It can also be slavicized as Gerasim.

Deir Hajla or Deir Hijleh is the Arabic name of the Greek Orthodox Monastery of Saint Gerasimus, a monastery located in the Jericho Governorate of the State of Palestine, in the West Bank, west of the River Jordan and north of the Dead Sea.

Christopher was Chalcedonian Patriarch of Antioch from 960 to 967.

Ibrahim ibn Yuhanna was a Byzantine bureaucrat, translator, and author from Antioch in the late 10th and early 11th centuries. He held the title of protospatharios and is often identified by this title in Arabic sources. Little is known for certain about his life, but he recounts in the Life of Christopher that he was a child in Antioch in the time of Patriarch Christopher and just before, meaning the late 950s and early 960s. He evidently found success in the imperial bureaucracy after the Byzantines conquered Antioch in 969, given his elevated title. The Life describes events in the time of Patriarch Nicholas II (1025–1030), so Ibrahim must have lived at least to the very late 1020s.

The Maronite Church is an Eastern Catholic sui iuris particular church in full communion with the pope and the worldwide Catholic Church, with self-governance under the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches. The head of the Maronite Church is Patriarch Bechara Boutros al-Rahi, who was elected in March 2011 following the resignation of Patriarch Nasrallah Boutros Sfeir. The seat of the Maronite Patriarchate is in Bkerke, northeast of Beirut, Lebanon. Officially known as the Antiochene Syriac Maronite Church, it is part of Syriac Christianity by liturgy and heritage.

The Loci communes (Commonplaces) or Capita theologica is a Byzantine Greek florilegium containing a mix of Judeo-Christian and pagan selections. It was originally compiled in the late 9th or early 10th century and subsequently enlarged around the year 1000.

Leontius of Damascus was a Syrian monk who wrote a biography in Greek of his teacher, Stephen of Mar Saba. It emphasises Stephen's asceticism and thaumaturgy (miracle-working), but is also a rich source for the history of Palestine in the eighth century. It has been translated into English.

Timothy of Kakhushta or Timothy the Stylite was a Syrian Melkite hermit and holy man known from an Arabic biography written not long after his death, The Life of the Holy and Virtuous Ascetic Timothy.

Paul of Antioch was a Melkite Christian monk, bishop and author who lived between the 11th and 13th centuries. His best known works are defences of Christianity written for Muslims and a treatise urging the conversion of Muslims and Jews.

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.