A comic strip is a sequence of cartoons, arranged in interrelated panels to display brief humor or form a narrative, often serialized, with text in balloons and captions. Traditionally, throughout the 20th and into the 21st century, these have been published in newspapers and magazines, with daily horizontal strips printed in black-and-white in newspapers, while Sunday papers offered longer sequences in special color comics sections. With the advent of the internet, online comic strips began to appear as webcomics.

User Friendly was a webcomic written by J. D. Frazer, also known by his pen name Illiad. Starting in 1997, the strip was one of the earliest webcomics to make its creator a living. The comic is set in a fictional internet service provider and draws humor from dealing with clueless users and geeky subjects. The comic ran seven days a week until 2009, when updates became sporadic, and since 2010 it had been in re-runs only. The webcomic was shut down in late February 2022, after an announcement from Frazer.

Webcomics are comics published on the internet, such as on a website or a mobile app. While many webcomics are published exclusively online, others are also published in magazines, newspapers, or comic books.

Fetus-X was a weekly romantic horror comic written and drawn by Eric Millikin and Casey Sorrow. Millikin is an American artist and former human anatomy lab embalmer and dissectionist. Sorrow is an internationally known American illustrator and printmaker.

Serializer.net was a webcomic subscription service and artist collective published by Joey Manley and edited by Tom Hart and Eric Millikin that existed from 2002 to 2013. Designed to showcase artistic alternative webcomics using the unique nature of the medium, the works on Serializer.net were described by critics as "high art" and "avant-garde". The project became mostly inactive in 2007 and closed alongside Manley's other websites in 2013.

Doctor Fun is a single-panel, gag webcomic by David Farley. It began in September 1993, making it one of the earliest webcomics, and ran until June 2006. Doctor Fun was part of United Media's website from 1995, but had parted ways by 2003. The comic was one of the longest-running webcomics before it concluded, having run for nearly thirteen years with over 2,600 strips. The webcomic has been compared to The Far Side.

The infinite canvas is the feeling of available space for a webcomic on the World Wide Web relative to paper. The term was introduced by Scott McCloud in his 2000 book Reinventing Comics, which supposes a web page can grow as large as needed. This infinite canvas gives infinite storytelling features and creators more freedom in how they present their artwork.

Where the Buffalo Roam was a comic strip by Hans Bjordahl that ran from 1987 to 1995. It was published on Usenet starting in 1991, making it one of the first online comic strips. Witches and Stitches was published earlier, in 1985, on CompuServe.

Web fiction is written works of literature available primarily or solely on the Internet. A common type of web fiction is the web serial. The term comes from old serial stories that were once published regularly in newspapers and magazines.

IBox was one of the first commercially available Internet connection software packages available for sale to the public. O'Reilly & Associates created and produced the package, in collaboration with Spry, Inc. Spry, Inc. also started up a commercial Internet service provider (ISP) called InterServ.

The Web Cartoonists' Choice Awards (WCCA) were annual awards in which established webcartoonists nominated and selected outstanding webcomics. The awards were held between 2001 and 2008, were mentioned in a New York Times column on webcomics in 2005, and have been mentioned as a tool for librarians.

Art Comics Daily is a pioneering webcomic first published in March 1995 by Bebe Williams, who lives in Arlington, Virginia, United States. The webcomic was published on the Internet rather than in print in order to reserve some artistic freedom. Williams has created two other daily webcomics – Bobby Rogers and Just Ask Mr-Know-It-All – and Art Comics Daily has been on permanent hiatus since 2007.

Eric Millikin is an American artist and activist based in Detroit, Michigan, and Richmond, Virginia. He is known for his pioneering work in artificial intelligence art, augmented and virtual reality art, conceptual art, Internet art, performance art, poetry, post-Internet art, video art, and webcomics. His work is often controversial, with political, romantic, occult, horror and black comedy themes.

T.H.E. Fox is a furry webcomic by Joe Ekaitis which ran from 1986 to 1998. It is among the earliest online comics, predating Where the Buffalo Roam by over five years. T.H.E. Fox was published on CompuServe, Q-Link and GEnie, and later on the Web as Thaddeus. Despite running weekly for several years, the comic never achieved Ekaitis' goal of print syndication. Updates became less frequent, and eventually stopped altogether.

NetBoy is a webcomic created by Stafford Huyler. Publishing began in May, 1994. Drawn as a stick figure, the comic character NetBoy is an Internet innocent with his greatest joy in life being "fast .GIFs."

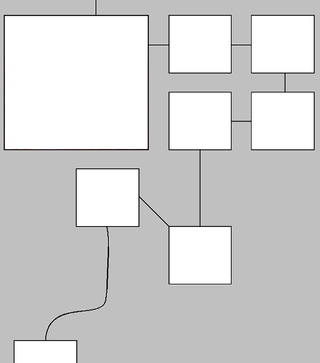

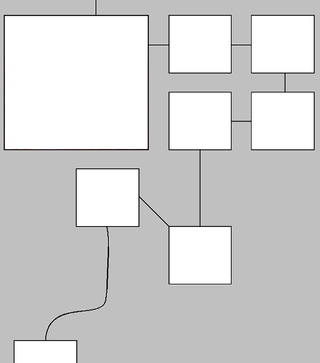

The history of webcomics follows the advances of technology, art, and business of comics on the Internet. The first comics were shared through the Internet in the mid-1980s. Some early webcomics were derivatives from print comics, but when the World Wide Web became widely popular in the mid-1990s, more people started creating comics exclusively for this medium. By the year 2000, various webcomic creators were financially successful and webcomics became more artistically recognized.

The business of webcomics involves creators earning a living through their webcomic, often using a variety of revenue channels. Those channels may include selling merchandise such as t-shirts, jackets, sweatpants, hats, pins, stickers, and toys, based on their work. Some also choose to sell print versions or compilations of their webcomics. Many webcomic creators make use of online advertisements on their websites, and possibly even product placement deals with larger companies. Crowdfunding through websites such as Kickstarter and Patreon are also popular choices for sources of potential income.

Notable events of the late 1990s in webcomics.

Webcomics in France are usually referred to as either blog BD or BD numérique. Early webcomics in the late 1990s and early 2000s primarily took on the form of personal blogs, where amateur artists told stories through their drawings. The medium rose in popularity in economic viability in the country in the late 2000s and early 2010s. The Turbomedia format, where a webcomic is presented more alike a slideshow, was popularized in France in the early 2010s.