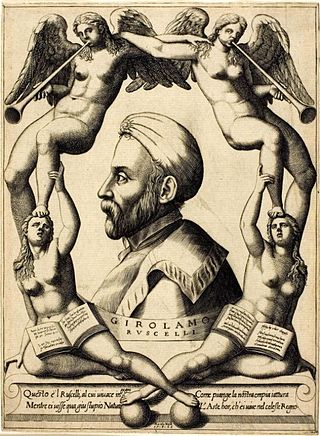

Biography

The date of Dolce's birth, long accepted as 1508, was more likely in 1510. [2] [3] Dolce's youth was difficult. His father, a former steward to the public attorneys (castaldo delle procuratorie) for the Republic of Venice, died when the boy was only two. [4] For his early studies, he depended on the support of two patrician families: that of the doge Leonardo Loredano (see Dolce's dedication of his Dialogue on Painting) and the Cornaro family, who financed his studies at Padua. [5] [6]

After he completed his studies, Dolce found work in Venice with the press of Gabriele Giolito de' Ferrari. [7] He was one of the most active intellectuals in 16th-century Venice. Claudia Di Filippo Bareggi claims that over the course of thirty-six years Dolce was responsible for 96 editions of his own original work, 202 editions of other writers, and at least 54 translations. [8] As a popularizer, he worked to make information available to the non-specialist, those too busy to learn Greek and Latin. [9]

Following a productive life as a scholar and author, Dolce died in January, 1568, and was buried in the church of San Luca in Venice, "although in which pavement tomb is unknown." [10]

Works

Dolce worked in most of the literary genres available at the time, including epic and lyric poetry, chivalric romance, comedy, tragedy, the prose dialogue, treatises (where he discussed women, [11] ill-married men, memory, the Italian language, gems, painting, and colors), encyclopedic summaries (of Aristotle's philosophy and world history), and historical works on major figures of the 16th century and earlier writers, such as Cicero, Ovid, Dante, and Boccaccio. [12] "From 1542, when Dolce first went to work for the Giolito, until [Giolito's] death in 1568, he edited 184 texts out of just over 700 titles published by Giolito." [9] These editions included works by Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio, Castiglione, Pietro Bembo, Lodovico Ariosto, Pietro Aretino, Angelo Poliziano, Jacopo Sannazzaro, and Bernardo Tasso. [13] And he translated into Italian works of authors such as Homer, Euripides, Catullus, Cicero, Horace, Ovid, Juvenal, the playwright Seneca, and Virgil. [14]

Writings on art

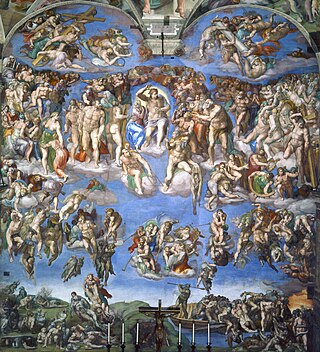

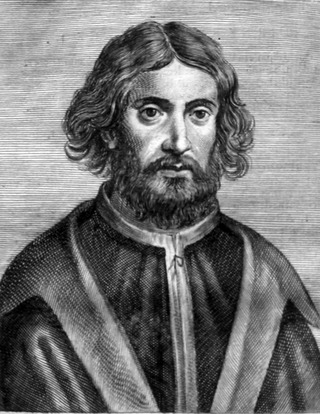

L'Aretino (1557), Dolce's main work on art, has been said to have been a riposte to Vasari's Lives of the Artists , whose first edition of 1550 did not even include Titian, which Vasari rectified in the second edition of 1568. [15] "In fact, scholars have demonstrated that Dolce's treatise was written long before Vasari's went to press". [16] It takes the form of a dialogue in three parts between Pietro Aretino, representing the Venetian point of view, and the Florentine humanist Giovanni Francesco Fabrini. [17] Beginning with a discussion of the principles of art, the dialogue moves on to a paragone or comparison between Raphael and Michelangelo, and to discuss a number of other contemporary painters, and then ends with a biography and appreciation of Titian. [18]

A clear hierarchy emerges from the book: of all the artists of his own century, Titian is the greatest, followed by the varied and harmonious Raphael, then the flawed Michelangelo. [19] It is uncertain how well he knew Titian at the time he wrote his life, which was the first published biography of the artist. There appear to be too many simple mistakes for the text to have been checked over by its subject. [20]

Dolce is a staunch partisan of the High Renaissance in general, and critical of Mannerism. [19] According to Anthony Blunt, the work was probably written in close collaboration with Aretino, who died a year before publication. Aretino's advances to Michelangelo had been rebuffed, and there is harsh criticism of his Last Judgment , repeating those already made by others, but usually couching objections in terms of decorum for such an important location as the Sistine Chapel, rather than morality as such—understandably, given Aretino's own notorious record in his life and works. [21]

Mark Roskill sees a different picture of the book's prehistory, with Dolce being a member of Aretino's "outer circle" for some years around 1537–42, before a slackening of relations; over this period Dolce became familiar with Aretino's strong but unsystematic thinking on art. After the publication of Vasari's Lives in 1550, the Venetian intellectual establishment felt the need for a Venetian counterblast, for which Dolce was probably chosen "by someone higher up in the hierarchy of Venetian humanists", and also supplied with some material. [22]

On Aretino's death in 1556, the work also took on another purpose: to serve as a memorial for him. It may have been at this point that the dialogue form was adopted. [23]

Dolce's approach in fact relies considerably on Vasari, who he is likely to have known, as Vasari's stay of 13 months in Venice in 1541–42 came when Dolce was closest to Aretino, at whose urging Vasari had made the visit. In turn, the added material on Titian in Vasari's 2nd edition of 1568 shows evidence of using L'Aretino (and also evidence of ignoring it), as well as the researches of the Florentine ambassador. The two men may have met in Vasari's brief visit in May 1566. [24]

Dolce's book continued to be admired as a treatise on art theory through to the 18th century, but more recently it is his biographical information that has been valued. A dual edition in French and Italian was published in 1735, and there were published translations in Dutch in 1756, German in 1757, and English in 1770. [25] Roskill's book includes L'Aretino in Italian and English on facing pages. [26]

Tragedies

As a dramatist he wrote numerous tragedies: Giocasta (1549, derived probably from Euripides' The Phoenician Women via the Latin translation of R. Winter), [27] Thieste, Medea, Didone, Ifigenia, Hecuba and Marianna. An English-language adaptation of the first of these, the Jocasta by George Gascoigne and Francis Kinwelmersh, was staged in 1566 at Gray's Inn in London. [28] His tragedy Didone (1547) was one of his more influential tragedies in Italy, a precursor of Pietro Metastasio's Didone abbandonata (1724). [29]

Comedies

He also wrote numerous comedies, including Il Marito, Il Ragazzo, Il Capitano, La Fabritia, and Il Ruffiano. [30]

Histories

Two of his histories—the Life of Charles V (1561) and the Life of Ferdinand I (1566)—were very successful in the sixteenth century. [9] His History of the World (Giornale delle historie del mondo, 1572, posthumous) is a lengthy calendar of notable historical and literary events, listed for each day of the year. The events he lists range from the origins of civilization to his own day. [31]

Treatises

His Treatise on Gems (Trattato delle gemme, 1565) falls into the lapidary tradition, with Dolce discussing not only the physical qualities of jewels but the power infused in them by the stars. [32] As his authorities, he cites Aristotle, the Persian philosopher Avicenna, Averroes, and the Libri mineralium of Albert the Great among others, but, according to Ronnie H. Terpening, he appears to have simply translated Camillo Leonardo's Speculum lapidum (1502) without crediting the earlier author. [33] In addition to translating Cicero's De Oratore (1547), Dolce authored several treatises on language, among them the Osservationi nella volgar lingua (1550). This was a linguistic and grammatical study in which Dolce draws examples from and comments on Dante, Boccaccio, and Ariosto, among others. [34]

Chivalric Romances

In the genre of chivalric romance, Dolce produced several reworkings of traditional material, including Sacripante (1536), Palmerino (1561), Primaleone, figliuolo di Palmerino (1562), and the posthumous Prime imprese del conte Orlando (The Early Deeds of Count Orlando) (1572). [35]

Classical Epic

Drawing heavily on Virgil, he wrote an epic poem on Aeneas, the Enea, published the year of his death. For those who had no knowledge of Greek or Latin, he compiled a work in ottava rima, L'Achille et l'Enea, joining Homer's epic to Virgil's, a work published posthumously in 1570. [30]

Editions of Other Writers

Among the authors edited by Dolce (for which see "Works" above), he focused most significantly on Ariosto. He edited three of Ariosto's comedies, La Lena (c. 1530), Il Negromante (c. 1530), and I Suppositi (1551); the poet's Rime (1557), and the Orlando furioso (1535). For the latter poem, he published a work explaining the more difficult aspects, the Espositioni (1542), and an analysis of the poem's figurative language, the Modi affigurati (1554).

Translations

Whether Dolce knew Greek or not has been questioned by Emmanuele Antonio Cicogna. [36] Nevertheless, using (but not acknowledging) Latin translations of authors such as Euripides, he translated the works of several Greek authors into Italian, among them Achilles Tatius (Leucippe and Clitophon, 1544), Homer's Odyssey (L'Ulisse, 1573, posthumous) and the History of the Greek Emperors (1569, posthumous) by Nicetas Acominatus. [37] He also translated various Latin authors, sometimes very loosely, other times, such as for Seneca's ten tragedies, with fidelity to the original. [38]

Ronnie H. Terpening concludes his book on Dolce by noting that

Truly, then as now, taking into account all his imperfections and those of the age, this is a worthy career for any man or woman of letters. Without his unstinting efforts, the history and development of Italian literature would surely be the poorer. In addition, if what others have said about him is accurate, Dolce was also a good man, for after 'indefatigable' the adjectives used most often to describe him are 'pacifico' and, of course, 'dolce.' In such a contentious age, these are simple but high words of praise indeed. (p. 169)