Diamond is a solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Diamond as a form of carbon is tasteless, odourless, strong, brittle solid, colourless in pure form, a poor conductor of electricity, and insoluble in water. Another solid form of carbon known as graphite is the chemically stable form of carbon at room temperature and pressure, but diamond is metastable and converts to it at a negligible rate under those conditions. Diamond has the highest hardness and thermal conductivity of any natural material, properties that are used in major industrial applications such as cutting and polishing tools. They are also the reason that diamond anvil cells can subject materials to pressures found deep in the Earth.

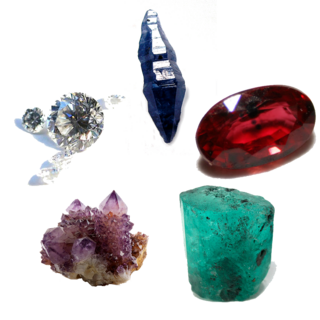

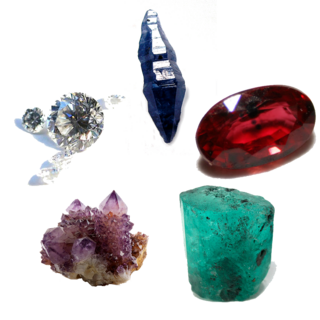

A gemstone is a piece of mineral crystal which, when cut or polished, is used to make jewelry or other adornments. Certain rocks and occasionally organic materials that are not minerals may also be used for jewelry and are therefore often considered to be gemstones as well. Most gemstones are hard, but some softer minerals such as brazilianite may be used in jewelry because of their color or luster or other physical properties that have aesthetic value. However, generally speaking, soft minerals are not typically used as gemstones by virtue of their brittleness and lack of durability.

The Mohs scale of mineral hardness is a qualitative ordinal scale, from 1 to 10, characterizing scratch resistance of minerals through the ability of harder material to scratch softer material.

Topaz is a silicate mineral made of aluminum and fluorine with the chemical formula Al2SiO4(F, OH)2. It is used as a gemstone in jewelry and other adornments. Common topaz in its natural state is colorless, though trace element impurities can make it pale blue or golden brown to yellow-orange. Topaz is often treated with heat or radiation to make it a deep blue, reddish-orange, pale green, pink, or purple.

Ruby is a pinkish red to blood-red colored gemstone, a variety of the mineral corundum. Ruby is one of the most popular traditional jewelry gems and is very durable. Other varieties of gem-quality corundum are called sapphires. Ruby is one of the traditional cardinal gems, alongside amethyst, sapphire, emerald, and diamond. The word ruby comes from ruber, Latin for red. The color of a ruby is due to the element chromium.

Diamond cutting is the practice of shaping a diamond from a rough stone into a faceted gem. Cutting diamonds requires specialized knowledge, tools, equipment, and techniques because of its extreme difficulty.

A cabochon is a gemstone that has been shaped and polished, as opposed to faceted. The resulting form is usually a convex (rounded) obverse with a flat reverse. Cabochon was the default method of preparing gemstones before gemstone cutting developed.

An abrasive is a material, often a mineral, that is used to shape or finish a workpiece through rubbing which leads to part of the workpiece being worn away by friction. While finishing a material often means polishing it to gain a smooth, reflective surface, the process can also involve roughening as in satin, matte or beaded finishes. In short, the ceramics which are used to cut, grind and polish other softer materials are known as abrasives.

Facets are flat faces on geometric shapes. The organization of naturally occurring facets was key to early developments in crystallography, since they reflect the underlying symmetry of the crystal structure. Gemstones commonly have facets cut into them in order to improve their appearance by allowing them to reflect light.

Stone carving is an activity where pieces of rough natural stone are shaped by the controlled removal of stone. Owing to the permanence of the material, stone work has survived which was created during our prehistory or past time.

A diamond simulant, diamond imitation or imitation diamond is an object or material with gemological characteristics similar to those of a diamond. Simulants are distinct from synthetic diamonds, which are actual diamonds exhibiting the same material properties as natural diamonds. Enhanced diamonds are also excluded from this definition. A diamond simulant may be artificial, natural, or in some cases a combination thereof. While their material properties depart markedly from those of diamond, simulants have certain desired characteristics—such as dispersion and hardness—which lend themselves to imitation. Trained gemologists with appropriate equipment are able to distinguish natural and synthetic diamonds from all diamond simulants, primarily by visual inspection.

A diamond blade is a saw blade which has diamonds fixed on its edge for cutting hard or abrasive materials. There are many types of diamond blade, and they have many uses, including cutting stone, concrete, asphalt, bricks, coal balls, glass, and ceramics in the construction industry; cutting semiconductor materials in the semiconductor industry; and cutting gemstones, including diamonds, in the gem industry.

A faceting machine is broadly defined as any device that allows the user to place and polish facets onto a mineral specimen. Machines can range in sophistication from primitive jamb-peg machines to highly refined, and highly expensive, commercially available machines. A major division among machines is found between those that facet diamonds and those that do not. Specialized equipment is required for diamond faceting, and faceting as an occupation rarely bridges the gap between diamond and non-diamond workmanship. A second division can be made between industrial faceting and custom/hobby faceting. The vast majority of jewelry-store gemstones are faceted either abroad in factories or entirely by machines. Custom jewelry is still commonly made of custom metalwork and mass-produced gemstones, but unusual cuts or particularly valuable gemstone material will likely be faceted on a personal faceting machine.

Lapidary clubs promote popular interest and education in lapidary, the craft of working, forming and finishing stone, minerals and gemstones. These clubs sponsor and provide means for their members to engage in all forms of jewellery making, cabochon cutting and faceting, carving, glass beadmaking and craft work. The clubs also promote and facilitate healthy outdoor activities in the form of field trips to various fossicking locations for the purpose of collecting gemstones or mineral specimens. Lapidary is particularly popular in the United States of America and Australia where large numbers of clubs were formed in the 1950s and 1960s.

A bezel is a wider and usually thicker section of the hoop of a ring, which may contain a gem or a flat surface. Rings are normally worn to display bezels on the upper or outer side of the finger. In gem-cutting the term bezel is used for those sloping facets of a cut stone that surround the flat table face, which is the large, horizontal facet on the top.

Hardstone carving, in art history and archaeology, is the artistic carving of semi-precious stones, such as jade, rock crystal, agate, onyx, jasper, serpentinite, or carnelian, and for objects made in this way. Normally the objects are small, and the category overlaps with both jewellery and sculpture. Hardstone carving is sometimes referred to by the Italian term pietre dure; however, pietra dura is the common term used for stone inlay work, which causes some confusion.

John Sinkankas was a Navy officer and aviator, gemologist, gem carver and gem faceter, author of many books and articles on minerals and gemstones, and a bookseller and bibliographer of rare books.

A lapidary is a text in verse or prose, often a whole book, that describes the physical properties and metaphysical virtues of precious and semi-precious stones, that is to say, a work on gemology. It was frequently used as a medical textbook, since it also includes practical information about the supposed medical application of each stone. Several lapidaries also provide information about the countries or regions where some rocks were thought to originate, and others speculate about the natural forces in control of their formation.

Dopping cement, dopping wax, or faceting wax is a thermal adhesive used by gem cutters to secure ("dop") a gemstone to a wooden or metal holder for grinding and lapping. Setters cement is a similar material used to secure a gemstone while setting or polishing.

Lapidary medicine is a pseudoscientific concept based on the belief that gemstones have healing properties. The source of the idea of lapidary medicine stems from information found in lapidaries, books giving "information about the properties and virtues of precious and semi-precious stones." These lapidaries not only provide understanding of the sale and production of items of lapidary medicine, but also provide information about common cultural practices and beliefs about gemstones.