Tibetan Buddhism is a form of Buddhism practiced in Tibet, Bhutan and Mongolia. It also has a sizable number of adherents in the areas surrounding the Himalayas, including the Indian regions of Ladakh, Darjeeling, Sikkim, and Zangnan, as well as in Nepal. Smaller groups of practitioners can be found in Central Asia, some regions of China such as Northeast China, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia and some regions of Russia, such as Tuva, Buryatia, and Kalmykia.

Vajrayāna, also known as Mantrayāna, Mantranāya, Guhyamantrayāna, Tantrayāna, Tantric Buddhism, and Esoteric Buddhism, is a Buddhist tradition of tantric practice that developed in Medieval India and spread to Tibet, Nepal, other Himalayan states, East Asia, parts of Southeast Asia and Mongolia.

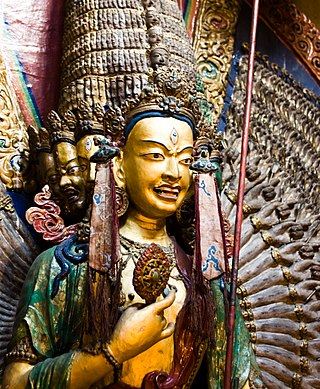

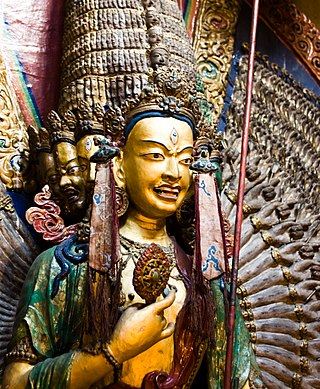

In Buddhism, Avalokiteśvara, also known as Lokeśvara and Chenrezig, is a tenth-level bodhisattva associated with great compassion (mahakaruṇā). He is often associated with Amitabha Buddha. Avalokiteśvara has numerous manifestations and is depicted in various forms and styles. In some texts, he is even considered to be the source of all Hindu deities.

Acala or Achala, also known as Acalanātha or Āryācalanātha, is a wrathful deity and dharmapala prominent in Vajrayana Buddhism and East Asian Buddhism.

Buddhist texts are religious texts that belong to, or are associated with, Buddhism and its traditions. There is no single textual collection for all of Buddhism. Instead, there are three main Buddhist Canons: the Pāli Canon of the Theravāda tradition, the Chinese Buddhist Canon used in East Asian Buddhist tradition, and the Tibetan Buddhist Canon used in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism.

In Buddhism, wrathful deities or fierce deities are the fierce, wrathful or forceful forms of enlightened Buddhas, Bodhisattvas or Devas ; normally the same figure has other, peaceful, aspects as well. Because of their power to destroy the obstacles to enlightenment, they are also termed krodha-vighnantaka, "Wrathful onlookers on destroying obstacles". Wrathful deities are a notable feature of the iconography of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism, especially in Tibetan art. These types of deities first appeared in India during the late 6th century, with its main source being the Yaksha imagery, and became a central feature of Indian Tantric Buddhism by the late 10th or early 11th century.

A dharmapāla is a type of wrathful god in Buddhism. The name means "dharma protector" in Sanskrit, and the dharmapālas are also known as the Defenders of the Justice (Dharma), or the Guardians of the Law. There are two kinds of dharmapala, Worldly Guardians (lokapala) and Wisdom Protectors (jnanapala). Only Wisdom Protectors are enlightened beings.

Buddhism includes a wide array of divine beings that are venerated in various ritual and popular contexts. Initially they included mainly Indian figures such as devas, asuras and yakshas, but later came to include other Asian spirits and local gods. They range from enlightened Buddhas to regional spirits adopted by Buddhists or practiced on the margins of the religion.

Dorje Shugden, also known as Dolgyal and Gyalchen Shugden, is an entity associated with the Gelug school, the newest of the schools of Tibetan Buddhism. Dorje Shugden is variously looked upon as a destroyed gyalpo, a minor mundane protector, a major mundane protector, an enlightened major protector whose outward appearance is that of a gyalpo, or as an enlightened major protector whose outward appearance is enlightened.

Hsuan Hua, also known as An Tzu, Tu Lun and Master Hua by his Western disciples, was a Chinese monk of Chan Buddhism and a contributing figure in bringing Chinese Buddhism to the United States in the late 20th century.

In Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism, the Five Tathāgatas (Skt: पञ्चतथागत, pañcatathāgata; or Five Wisdom Tathāgatas, are the five cardinal male and female Buddhas that are inseparable co-equals, although the male cardinal Buddhas are more often represented. Collectively, the male and female Buddhas are known as the Five Buddha Families. The five are also called the Five Great Buddhas, and the Five Jinas.

Mahākāla is a deity common to Hinduism and Buddhism.

The Śūraṅgama Sūtra is a Mahayana Buddhist sutra that has been especially influential on Korean Buddhism and Chinese Buddhism. It was particularly important for Zen/Chan Buddhism. The doctrinal outlook of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra is that of Buddha-nature, Yogacara thought, and esoteric Buddhism.

Buddhist tantric literature refers to the vast and varied literature of the Vajrayāna Buddhist traditions. The earliest of these works are a genre of Indian Buddhist tantric scriptures, variously named Tantras, Sūtras and Kalpas, which were composed from the 7th century CE onwards. They are followed by later tantric commentaries, original compositions by Vajrayana authors, sādhanas, ritual manuals, collections of tantric songs (dohās) odes (stotra), or hymns, and other related works. Tantric Buddhist literature survives in various languages, including Sanskrit, Tibetan, and Chinese. Most Indian sources were composed in Sanskrit, but numerous tantric works were also composed in other languages like Tibetan and Chinese.

Sitātapatrā is a bodhisattva and protector against supernatural danger in Buddhism. She is venerated in both the Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions. She is also known as Usnisasitatapatra or Uṣṇīṣa Sitātapatrā. It is believed that Sitātapatrā is a powerful independent deity emanated by Gautama Buddha from his Uṣṇīṣa. Whoever practices her mantra will be reborn in Amitābha's pure land of Sukhāvatī as well as gaining protection against supernatural danger and witchcraft.

According to Tibetan Buddhist myth, Gyalpo Pehar is a spirit belonging to the gyalpo class. When Padmasambhava arrived in Tibet in the eighth century, he subdued all gyalpo spirits and put them under control of Gyalpo Pehar, who promised not to harm any sentient beings and was made the chief guardian spirit of Samye during the reign of Trisong Deutsen. Pehar is the leader of a band of five gyalpo spirits and would later become the protector deity of Nechung Monastery in the 17th century under the auspices of the Fifth Dalai Lama.

The Shurangama or Śūraṅgama mantra is a dhāraṇī or long mantra of Buddhist practice in East Asia. Although relatively unknown in modern Tibet, there are several Śūraṅgama Mantra texts in the Tibetan Buddhist canon. It has strong associations with the Chinese Chan Buddhist tradition.

Chinese Esoteric Buddhism refers to traditions of Tantra and Esoteric Buddhism that have flourished among the Chinese people. The Tantric masters Śubhakarasiṃha, Vajrabodhi and Amoghavajra, established the Esoteric Buddhist Zhenyan tradition from 716 to 720 during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang. It employed mandalas, mantras, mudras, abhiṣekas, and deity yoga. The Zhenyan tradition was transported to Japan as Shingon Buddhism by Kūkai as well as influencing Korean Buddhism and Vietnamese Buddhism. The Song dynasty (960–1279) saw a second diffusion of Esoteric texts. Esoteric Buddhist practices continued to have an influence into the late imperial period and Tibetan Buddhism was also influential during the Yuan dynasty period and beyond. In the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) through to the modern period, esoteric practices and teachings became absorbed and merged with the other Chinese Buddhist traditions to a large extent.

Classes of Tantra in Tibetan Buddhism refers to the categorization of Buddhist tantric scriptures in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism. Tibetan Buddhism inherited numerous tantras and forms of tantric practice from medieval Indian Buddhist Tantra. There were various ways of categorizing these tantras in India. In Tibet, the Sarma schools categorize tantric scriptures into four classes, while the Nyingma (Ancients) school use six classes of tantra.

Vināyaka, Vighnāntaka, or Gaṇapati is a Buddhist deity venerated in various traditions of Mahayana Buddhism. He is the Buddhist equivalent of the Hindu god Ganesha. In Tibetan Buddhism he is also known as the Red Lord of Hosts. In Japanese Buddhism he is also known as Kangiten or Shōten.