Live from Death Row, published in May 1995, is a memoir by Mumia Abu-Jamal, an American journalist and activist from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He is known for having been convicted of the murder of a city police officer and sentenced to death in 1982, in a trial that Amnesty International suspected of lacking impartiality. Abu-Jamal wrote this book while on death row. He has always maintained his innocence. Publishers Addison-Wesley paid Abu-Jamal a $30,000 advance for the book.

Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972), was a landmark criminal case in which the United States Supreme Court invalidated all then existing legal constructions for the death penalty in the United States. It was a 5–4 decision, with each member of the majority writing a separate opinion. Following Furman, in order to reinstate the death penalty, states had to at least remove arbitrary and discriminatory effects in order to satisfy the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

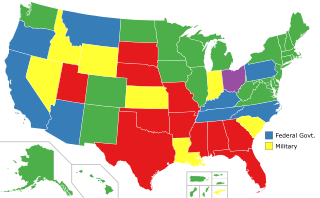

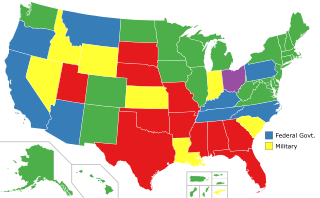

In the United States, capital punishment is a legal penalty throughout the country at the federal level, in 27 states, and in American Samoa. It is also a legal penalty for some military offenses. Capital punishment has been abolished in 23 states and in the federal capital, Washington, D.C. It is usually applied for only the most serious crimes, such as aggravated murder. Although it is a legal penalty in 27 states, 20 states currently have the ability to execute death sentences, with the other seven, as well as the federal government, being subject to different types of moratoriums.

The U.S. state of Washington enforced capital punishment until the state's capital punishment statute was declared null and void and abolished in practice by a state Supreme Court ruling on October 11, 2018. The court ruled that it was unconstitutional as applied due to racial bias however it did not render the wider institution of capital punishment unconstitutional and rather required the statute to be amended to eliminate racial biases. From 1904 to 2010, 78 people were executed by the state; the last was Cal Coburn Brown on September 10, 2010. In April 2023, Governor Jay Inslee signed SB5087 which formally abolished capital punishment in Washington State and removed provisions for capital punishment from state law.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. is an American civil rights organization and law firm based in New York City.

Gregg v. Georgia, Proffitt v. Florida, Jurek v. Texas, Woodson v. North Carolina, and Roberts v. Louisiana, 428 U.S. 153 (1976), is a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court. It reaffirmed the Court's acceptance of the use of the death penalty in the United States, upholding, in particular, the death sentence imposed on Troy Leon Gregg. The set of cases is referred to by a leading scholar as the July 2 Cases, and elsewhere referred to by the lead case Gregg. The court set forth the two main features that capital sentencing procedures must employ in order to comply with the Eighth Amendment ban on "cruel and unusual punishments". The decision essentially ended the de facto moratorium on the death penalty imposed by the Court in its 1972 decision in Furman v. Georgia 408 U.S. 238 (1972). Justice Brennan dissent famously argued that "The calculated killing of a human being by the State involves, by its very nature, a denial of the executed person's humanity... An executed person has indeed 'lost the right to have rights."

Capital punishment in India is a legal penalty for some crimes under the country's main substantive penal legislation, the Indian Penal Code, as well as other laws. Executions are carried out by hanging as the primary method of execution per Section 354(5) of the Criminal Code of Procedure, 1973 is "Hanging by the neck until dead", and is imposed only in the 'rarest of cases'.

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976), was a United States Supreme Court case that established that laws that have a racially discriminatory effect but were not adopted to advance a racially discriminatory purpose are valid under the U.S. Constitution.

Troy Leon Gregg was the first condemned individual whose death sentence was upheld by the United States Supreme Court after the Court's decision in Furman v. Georgia invalidated all previous capital punishment laws in the United States. He later participated in the first successful escape from Reidsville State Prison death row with three other death row inmates, but was killed later that night by Timothy McCorquodale.

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967), found in favor of the petitioner (Whitus), who had been convicted for murder, and as such reversed their convictions. This was due to the Georgia jury selection policies, in which it was alleged racial discrimination had occurred.

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968), was a U.S. Supreme Court case where the court ruled that a state statute providing the state unlimited challenge for cause of jurors who might have any objection to the death penalty gave too much bias in favor of the prosecution.

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973), is a US employment law case by the United States Supreme Court regarding the burdens and nature of proof in proving a Title VII case and the order in which plaintiffs and defendants present proof. It was the seminal case in the McDonnell Douglas burden-shifting framework.

The Capital Jury Project (CJP) is a consortium of university-based research studies on the decision-making of jurors in death penalty cases in the United States. It was founded in 1991 and is supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF). The goal of the CJP is to determine whether jurors' sentencing decisions conform to the constitution and do not reflect the arbitrary decisions the United States Supreme Court found when it ruled the death penalty unconstitutional in Furman v. Georgia. That 1972 Supreme Court decision eliminated the death penalty, which was not reinstated until Gregg v. Georgia in 1976.

William Henry Hance was an American serial killer and soldier who is believed to have murdered four women and molested 3 of the women in and around military bases before his arrest in 1978. He was convicted of murdering three of them, and not brought to trial on the fourth. He was executed by the state of Georgia in the electric chair.

Julian Owen Forrester was a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia.

David Christopher Baldus was an American legal scholar. He was the Joseph B. Tye Professor of Law at the University of Iowa. He held the position from 1969 until his death in 2011. His research focused on law and social science and he conducted extensive research on the death penalty in the United States.

The debate over capital punishment in the United States existed as early as the colonial period. As of April 2022, it remains a legal penalty within 28 states, the federal government, and military criminal justice systems. The states of Colorado, Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, New Hampshire, Virginia, and Washington abolished the death penalty within the last decade alone.

Glossip v. Gross, 576 U.S. 863 (2015), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held, 5–4, that lethal injections using midazolam to kill prisoners convicted of capital crimes do not constitute cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The Court found that condemned prisoners can only challenge their method of execution after providing a known and available alternative method.

The relationship between race and capital punishment in the United States has been studied extensively. As of 2014, 42 percent of those on death row in the United States were Black. As of October 2002, there were 12 executions of White defendants where the murder victim was Black, however, there were 178 executed defendants who were Black with a White murder victim. Since then, the number of white defendants executed where the murder victim was black has increased to just 21, whereas the number of Black defendants executed where the murder victim was White has increased to 299. 54 percent of people wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death in the United States are black.

The California Racial Justice Act of 2020 bars the state from seeking or securing a criminal conviction or imposing a sentence on the basis of race, ethnicity or national origin. The Act, in part, allows a person to challenge their criminal case if there are statistical disparities in how people of different races are either charged, convicted or sentenced of crimes. The Act counters the effect of the widely criticized 1987 Supreme Court decision in McClesky v. Kemp, which rejected the use of statistical disparities in the application of the death penalty to prove the kind of intentional discrimination required for a constitutional violation. The Act, however, goes beyond countering McClesky to also allow a defendant to challenge their charge, conviction or sentence if a judge, attorney, law enforcement officer, expert witness, or juror exhibited bias or animus towards the defendant because of their race, ethnicity, or national origin or if one of those same actors used racially discriminatory language during the trial. The CRJA only applies prospectively to cases sentenced after January 1, 2021. The Act is codified in Sections 745, 1473 and 1473.7 of the California Penal Code.