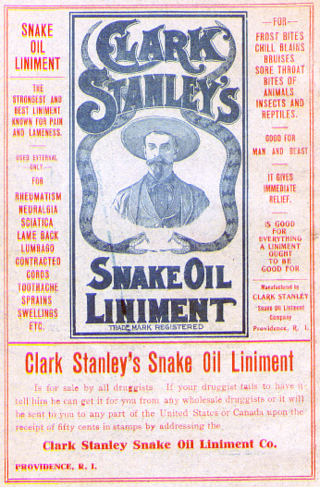

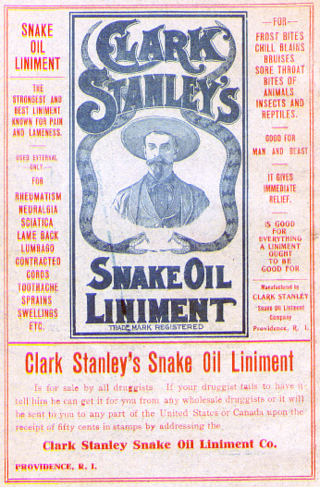

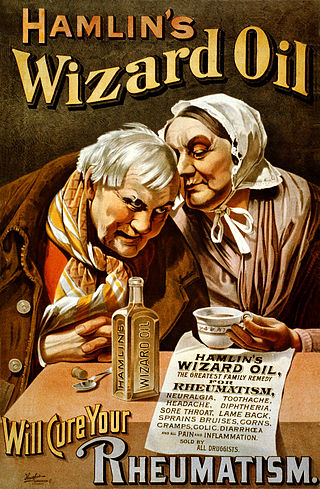

Snake oil is a term used to describe deceptive marketing, health care fraud, or a scam. Similarly, snake oil salesman is a common label used to describe someone who sells, promotes, or is a general proponent of some valueless or fraudulent cure, remedy, or solution. The term comes from the "snake oil" that used to be sold as a cure-all elixir for many kinds of physiological problems. Many 19th-century United States and 18th-century European entrepreneurs advertised and sold mineral oil as "snake oil liniment", making claims about its efficacy as a panacea. Patent medicines that claimed to be a panacea were extremely common from the 18th century until the 20th, particularly among vendors masking addictive drugs such as cocaine, amphetamine, alcohol, and opium-based concoctions or elixirs, to be sold at medicine shows as medication or products promoting health.

Quackery, often synonymous with health fraud, is the promotion of fraudulent or ignorant medical practices. A quack is a "fraudulent or ignorant pretender to medical skill" or "a person who pretends, professionally or publicly, to have skill, knowledge, qualification or credentials they do not possess; a charlatan or snake oil salesman". The term quack is a clipped form of the archaic term quacksalver, derived from Dutch: kwakzalver a "hawker of salve" or rather somebody who boasted about their salves, more commonly known as ointments. In the Middle Ages the term quack meant "shouting". The quacksalvers sold their wares at markets by shouting to gain attention.

A patent medicine is a non-prescription medicine or medicinal preparation that is typically protected and advertised by a trademark and trade name, and claimed to be effective against minor disorders and symptoms, as opposed to a prescription drug that could be obtained only through a pharmacist, usually with a doctor's prescription, and whose composition was openly disclosed. Many over-the-counter medicines were once ethical drugs obtainable only by prescription, and thus are not patent medicines.

Opodeldoc is a medical plaster or liniment invented, or at least named, by the German Renaissance physician Paracelsus in the 1500s. In modern form opodeldoc is a mixture of soap in alcohol, to which camphor and sometimes a number of herbal essences, most notably wormwood, are added.

A charlatan is a person practicing quackery or a similar confidence trick in order to obtain money, power, fame, or other advantages through pretense or deception. One example of a charlatan appears in the Canterbury Tales story "The Pardoner's Tale," with the Pardoner who tricks sinners into buying fake religious relics. Synonyms for charlatan include shyster, quack, or faker. Quack is a reference to quackery or the practice of dubious medicine, including the sale of snake oil, or a person who does not have medical training who purports to provide medical services.

In cryptography, snake oil is any cryptographic method or product considered to be bogus or fraudulent. The name derives from snake oil, one type of patent medicine widely available in 19th century United States.

A panacea is any supposed remedy that is claimed to cure all diseases and prolong life indefinitely. Named after the Greek goddess of universal remedy Panacea, it was in the past sought by alchemists in connection with the elixir of life and the philosopher's stone, a mythical substance that would enable the transmutation of common metals into gold. Through the 18th and 19th centuries, many "patent medicines" were claimed to be panaceas, and they became very big business. The term "panacea" is used in a negative way to describe the overuse of any one solution to solve many different problems, especially in medicine. The word has acquired connotations of snake oil and quackery.

Hulbert Harrington Warner (1842–1923) was a Rochester, New York businessman and philanthropist who made his fortune from the sales of patent medicine.

Sequah Medicine Company was a medicine company that began in 1887 as the Sequah Medicine Co Ltd. It sold patent medicines such as prairie flower and Indian oil using traveling salesman, known as Sequahs. The traveling salesmen were quack doctors. The original Sequah was William Henry Hartley, who founded the company selling supposed Native American remedies in Great Britain and Ireland. The successful pitch quickly drew imitators, to the annoyance of Hartley. One such example is Peter Alexander Gordon, who went under the pseudonym James Kaspar. Gordon sold the Sequah Patent Medicine in Great Britain, Ireland, the West Indies and North America and South Africa.

Hadacol was a patent medicine marketed as a vitamin supplement. Its principal attraction, however, was that it contained 12 percent alcohol, which made it quite popular in the dry counties of the southern United States. It was the product of four-term Louisiana State Senator Dudley J. LeBlanc, a Democrat from Erath in Vermilion Parish in southwestern Louisiana. He was not a medical doctor, nor a registered pharmacist, but had a strong talent for self-promotion. Time magazine once described him as "a stem-winding salesman who knows every razzle-dazzle switch in the pitchman's trade".

Doctor Earl Sawyer Sloan was an American entrepreneur and philanthropist. His parents were Andrew Sloan and Susan Bass Clark Sloan.

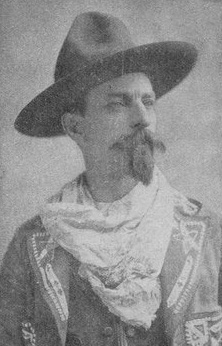

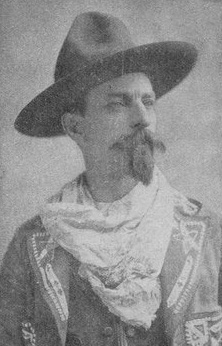

Clark Stanley was an American herbalist and quack doctor who marketed a "snake oil" as a patent medicine, styling himself the "Rattlesnake King" until his fraudulent products were exposed in 1916, popularizing the pejorative title of the "snake oil salesman".

James Henry McLean was a U.S. Representative from Missouri.

Ramblin' Tommy Scott, aka "Doc" Tommy Scott, was an American country and rockabilly musician.

William John Aloysius Bailey was an American patent medicine inventor and salesman. A Harvard University dropout, Bailey falsely claimed to be a doctor of medicine and promoted the use of radioactive radium as a cure for coughs, flu, and other common ailments. Although Bailey's Radium Laboratories in East Orange, New Jersey, was continually investigated by the Federal Trade Commission, he died wealthy from his many devices and products, including an aphrodisiac called Arium, marketed as a restorative that "renewed happiness and youthful thrill into the lives of married peoples whose attractions to each other had weakened."

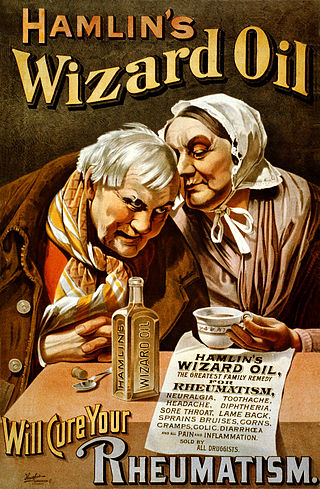

Hamlin's Wizard Oil was an American patent medicine sold as a cure-all under the slogan "There is no Sore it will Not Heal, No Pain it will not Subdue."

Patanjali Ayurved is an Indian multinational conglomerate holding company, based in Haridwar. It was founded by Ramdev and Balkrishna in 2006. Its office is in Delhi, with manufacturing units and headquarters in the industrial area of Haridwar. The company manufactures cosmetics, ayurvedic medicine, personal care and food products. The CEO of the company, with a 94-percent share hold, is Balkrishna. Ramdev represents the company and makes strategic decisions.

Bile Beans was a laxative and tonic first marketed in the 1890s. The product supposedly contained substances extracted from a hitherto unknown vegetable source by a fictitious chemist known as Charles Forde. In the early years Bile Beans were marketed as "Charles Forde's Bile Beans for Biliousness", and sales relied heavily on newspaper advertisements. Among other cure-all claims, Bile Beans promised to "disperse unwanted fat" and "purify and enrich the blood".

Maude Mayberg, also known as Madame Yale, was a beauty products and patent medicine entrepreneur and saleswoman.