Raffles v Wichelhaus [1864] EWHC Exch J19, often called "The Peerless" case, is a leading case on mutual mistake in English contract law. The case established that where there is latent ambiguity as to an essential element of the contract, the Court will attempt to find a reasonable interpretation from the context of the agreement before it will void it.

Estoppel in English law is a doctrine that may be used in certain situations to prevent a person from relying upon certain rights, or upon a set of facts which is different from an earlier set of facts.

Offer and acceptance are generally recognized as essential requirements for the formation of a contract. Analysis of their operation is a traditional approach in contract law. This classical approach to contract formation has been modified by developments in the law of estoppel, misleading conduct, misrepresentation, unjust enrichment, and power of acceptance.

In contract law, a mistake is an erroneous belief, at contracting, that certain facts are true. It can be argued as a defense, and if raised successfully, can lead to the agreement in question being found void ab initio or voidable, or alternatively, an equitable remedy may be provided by the courts. Common law has identified three different types of mistake in contract: the 'unilateral mistake', the 'mutual mistake', and the 'common mistake'. The distinction between the 'common mistake' and the 'mutual mistake' is important.

Balfour v Balfour [1919] 2 KB 571 is a leading English contract law case. It held that there is a rebuttable presumption against an intention to create a legally enforceable agreement when the agreement is domestic in nature.

Smith v Hughes (1871) LR 6 QB 597 is an English contract law case. In it, Blackburn J set out his classic statement of the objective interpretation of people's conduct when entering into a contract. The case regarded a mistake made by Mr. Hughes, a horse trainer, who bought a quantity of oats that were the same as a sample he had been shown. However, Hughes had misidentified the kind of oats: his horse could not eat them, and he refused to pay for them. Smith, the oat supplier, sued for Hughes to complete the sale as agreed. The court sided with Smith, as he provided the oats Hughes agreed to buy. That Hughes made a mistake was his own fault, as he had not been misled by Smith. Since Smith had made no fault, there was no mutual mistake, and the sale contract was still valid.

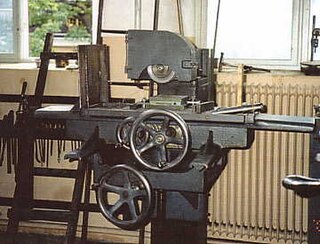

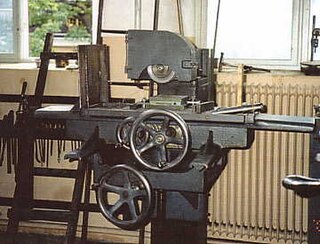

Butler Machine Tool Co Ltd v Ex-Cell-O Corp (England) Ltd [1977] EWCA Civ 9 is a leading English contract law case. It concerns the problem found among some large businesses, with each side attempting to get their preferred standard form agreements to be the basis for a contract.

Rose & Frank Co v JR Crompton & Bros Ltd [1924] is a leading decision on English contract law, regarding the intention to create legal relations in commercial arrangements. In the Court of Appeal, Atkin LJ delivered an important dissenting judgment which was upheld by the House of Lords.

Nethermere Ltd v Gardiner And Another [1984] ICR 612 is a UK labour law case in the Court of Appeal in the field of home work and vulnerable workers. Many labour and employment rights, such as unfair dismissal, in Britain depend on one's status as an "employee" rather than being "self-employed", or some other "worker". This case stands for the proposition that where "mutuality of obligation" between employers and casual or temporary workers exists to offer work and accept it, the court will find that the applicant has a "contract of employment" and is therefore an employee.

English contract law is the body of law that regulates legally binding agreements in England and Wales. With its roots in the lex mercatoria and the activism of the judiciary during the Industrial Revolution, it shares a heritage with countries across the Commonwealth, from membership in the European Union, continuing membership in Unidroit, and to a lesser extent the United States. Any agreement that is enforceable in court is a contract. A contract is a voluntary obligation, contrasting to the duty to not violate others rights in tort or unjust enrichment. English law places a high value on ensuring people have truly consented to the deals that bind them in court, so long as they comply with statutory and human rights.

Gibson v Manchester City Council[1979] UKHL 6 is an English contract law case in which the House of Lords strongly reasserted that agreement only exists when there is a clear offer mirrored by a clear acceptance.

In English contract law, an agreement establishes the first stage in the existence of a contract. The three main elements of contractual formation are whether there is (1) offer and acceptance (agreement) (2) consideration (3) an intention to be legally bound.

A contract is an agreement that specifies certain legally enforceable rights and obligations pertaining to two or more parties. A contract typically involves consent to transfer of goods, services, money, or promise to transfer any of those at a future date. The activities and intentions of the parties entering into a contract may be referred to as contracting. In the event of a breach of contract, the injured party may seek judicial remedies such as damages or equitable remedies such as specific performance or rescission. A binding agreement between actors in international law is known as a treaty.

R v Clarke, is court case decided by the High Court of Australia in the law of contract.

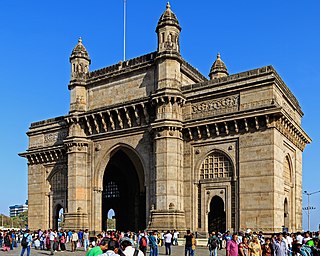

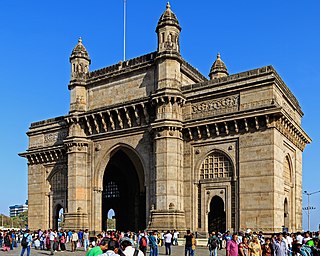

The Indian Contract Act, 1872 prescribes the law relating to contracts in India and is the key act regulating Indian contract law. The Act is based on the principles of English Common Law. It is applicable to all the states of India. It determines the circumstances in which promises made by the parties to a contract shall be legally binding. Under Section 2(h), the Indian Contract Act defines a contract as an agreement enforceable by Law.

Contract law regulates the obligations established by agreement, whether express or implied, between private parties in the United States. The law of contracts varies from state to state; there is nationwide federal contract law in certain areas, such as contracts entered into pursuant to Federal Reclamation Law.

The Household Fire and Carriage Accident Insurance Company (Limited) v Grant (1878–79) LR 4 Ex D 216 is an English contract law case concerning the "postal rule". It contains an important dissenting judgment by Bramwell LJ, who wished to dispose of it.

Intention to create legal relations, otherwise an "intention to be legally bound", is a doctrine used in contract law, particularly English contract law and related common law jurisdictions.

Merritt v Merritt [1970] EWCA Civ 6 is an English contract law case, on the matter of creating legal relations. While under the principles laid out in Balfour v Balfour, domestic agreements between spouses are rarely legally enforceable, this principle was rebutted where two spouses who formed an agreement over their matrimonial home were not on good terms.

Dickinson v Dodds (1876) 2 Ch D 463 is an English contract law case heard by the Court of Appeal, Chancery Division, which held that notification by a third party of an offer's withdrawal is effective just like a withdrawal by the person who made an offer. The significance of this case to many students of contract law is that a promise to keep an offer open is itself a contract which must have some consideration.